Advertisement

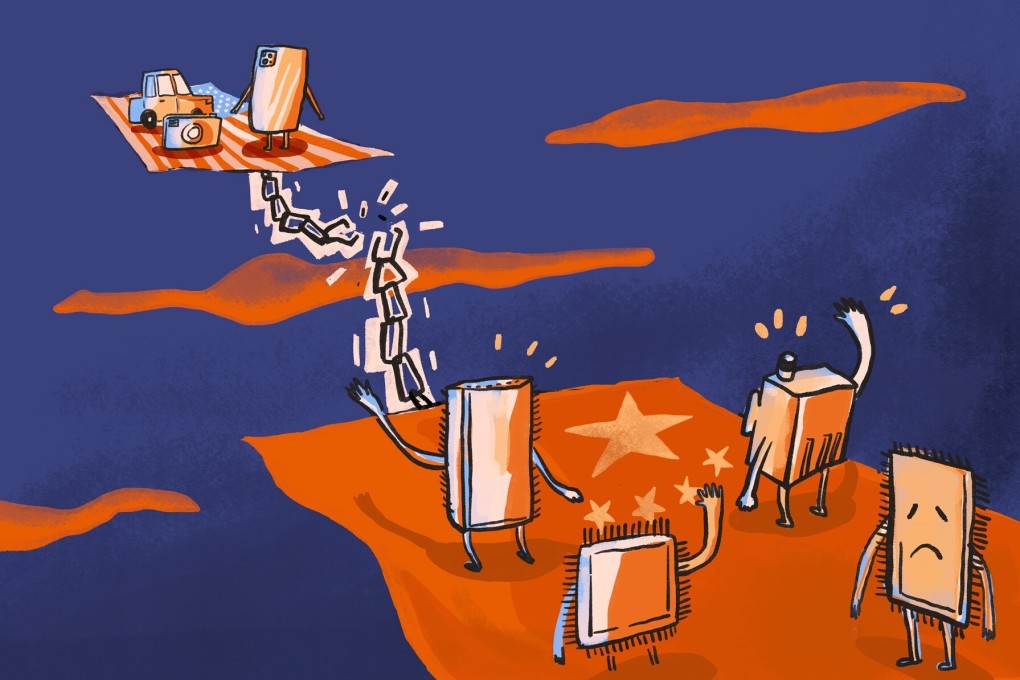

US-China tech war: how one dumped Apple supplier’s fate shows the pain of global supply chain politics

- Ofilm was kicked off Apple’s supplier list over allegations that it was involved in a programme that transferred ethnic minorities from Xinjiang to work

- Most of the workers the Post spoke to were from Jiangxi, not Xinjiang

7-MIN READ7-MIN

28

In the third instalment of a five-part series on US-China technology policy, Tracy Qu and Jane Zhang visited a factory in the Jiangxi provincial capital of Nanchang, to see how a recently-blacklisted camera maker for Apple’s smartphones has come to symbolise the pain of supply chain politics. The first part is here, and the second part on Huawei is here.

When Huang started work at Ofilm Group’s factory on June 7 in his second stint at the factory that produces camera modules, touch screens and other components used in electronic gadgets, he noticed several glaring omissions in his orientation for new hires.

“When I attended the [new hire] training the first time, they showed us photos with Apple executives. They were very confident then,” said Huang, 22, speaking to a South China Morning Post reporter at a concession stand near the optics factory and who would not give his full name as he is not authorised to speak with the media. “But they did not show the pictures this time.”

Advertisement

The absence of the world’s most valuable company was not an oversight. Shenzhen-based Ofilm, which has many factories in the Jiangxi provincial capital of Nanchang, was kicked off Apple’s supplier list in mid-March over allegations that it was involved in a government programme that transferred ethnic minorities from Xinjiang to work at the company’s factories.

Advertisement

Ofilm declined to comment on Bloomberg’s report that the American company had severed its contracts several months ago.

Ofilm’s shares have fallen by about 10 per cent since mid-March and the company’s fall from grace is one of the clearest examples yet of how obscure parts of the global manufacturing supply chain can be ensnared by US-China relations, which deteriorated to their worst point in decades during former US President Donald Trump’s tenure.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x