From war to peace and now prosperity in rural Vietnam

Three generations of a steel-working dynasty from Bach Ninh province illustrate how the country has changed in the past 80 years

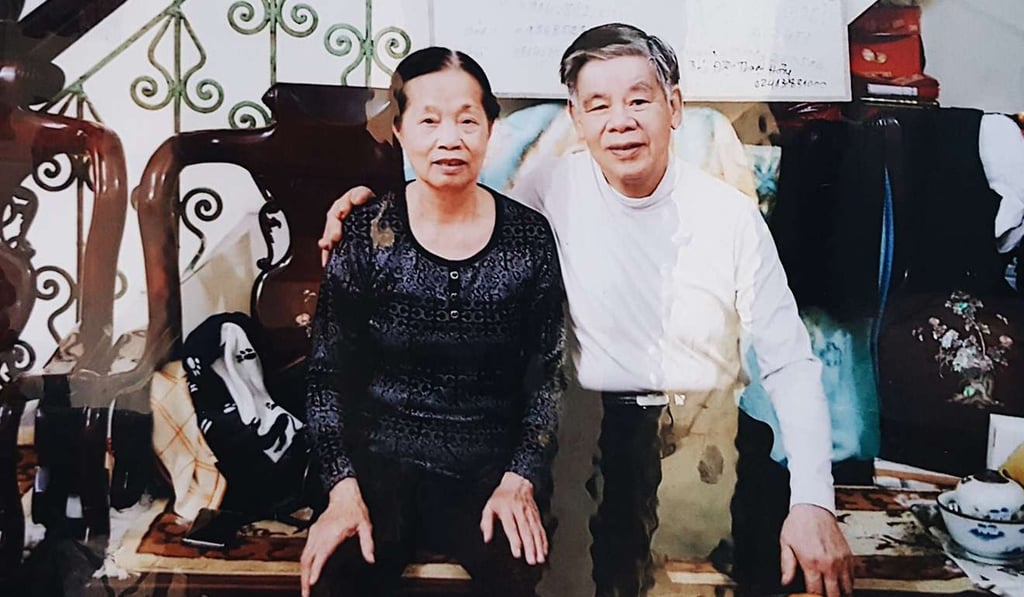

Now 82 years old, Tran Van Quy speaks haltingly about the past.

“I have lived through two wars – against the French and the Americans. The fighting started when I was only eight years old so I never went to school.

“We suffered more with the French; they killed men and raped women. The Americans were different. We never saw them. They just dropped bombs.

“But the French burnt down our family home. Thirty-two people were killed by the cannons they fired into the village. Kids don’t really know anger but they know fear and I was very afraid.”

Born into a well-to-do, land-owning family, Tran remembers his pre-war childhood as an idyllic time – running through his family’s large home, looking after the water buffaloes and eating rice every day.