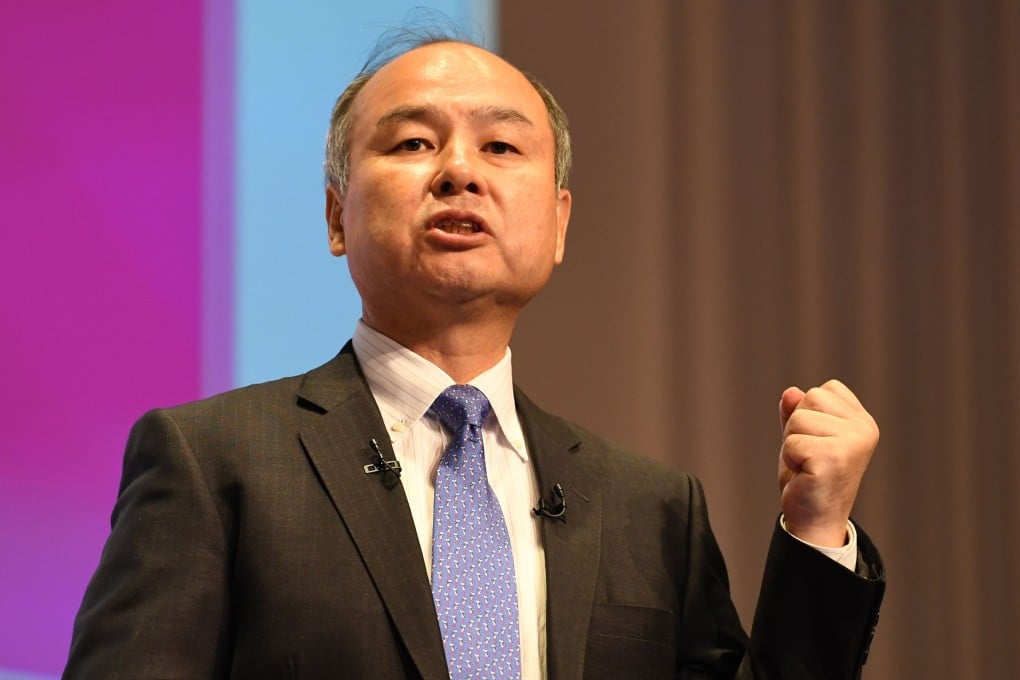

After SoftBank’s massive losses and Jack Ma’s departure, has CEO Masayoshi Son lost his golden touch?

- Japan’s SoftBank Group reported a US$12.7 billion loss, largely from its investments in Uber, WeWork and Oyo, and compounded by the coronavirus

- With more boardroom departures, including Alibaba founder Jack Ma, and Son seemingly likening himself to Jesus, who can rein in his risk-taking impulses?

But with billions in losses from some of his biggest recent investments and a growing list of departures from his boardrooms, there is speculation whether an increasingly isolated Son has lost his lauded Midas touch.

On Monday, Son announced SoftBank Group had lost 1.36 trillion yen (US$12.7 billion) in the year to March. The red ink largely stemmed from losses of 1.9 trillion yen (US$17.7 billion) at SoftBank’s US$100 billion Vision Fund, caused by misfiring investments in Uber, WeWork and Oyo, among others, which were exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic.

On a conference call with investors after the earnings announcement, Son pointed out that Jesus was also criticised and misunderstood, leading to some derision and concern that the unshakeable confidence which drove his bold moves over the years had morphed into a messiah complex. On Tuesday, Son took to Twitter to say: “The reason for failure lies not outside, but with me. There is no moving forward without admitting that.”