What’s the secret behind India’s IIT, which produced Twitter chief Parag Agrawal and other tech titans?

- The Indian Institute of Technology is an elite network of 23 engineering schools which boasts the ‘the most difficult admission exam on the planet’

- ‘IITians’ include Alphabet’s Sundar Pichai, Adobe’s Shantanu Narayen, Micron Technology’s Nikesh Arora and Sun Microsystems’ Vinod Khosla

Above the imposing main entrance of the first Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), which opened back in 1951, is the motto “Service to the Nation”. For years, as many graduates of the country’s elite network of engineering schools headed off for greener pastures in the US, the joke among Indians was “which nation?”.

Twitter’s new chief Parag Agrawal recently joined a long list of talented IIT graduates who have become tech titans in Silicon Valley, including Alphabet’s Sundar Pichai, Adobe’s Shantanu Narayen, Micron Technology’s Nikesh Arora and Sun Microsystems’ Vinod Khosla to name just a few.

By global standards, IIT – which has grown to 23 campuses around India – is way down the academic league tables, according to the widely used QS World University rankings. IIT Bombay fared best of all Indian educational institutions in 2021, coming 177 out of the leading 200 universities in the QS global rankings. By contrast, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) was in top position. While IIT scores well on employer reputation, with 70 out of 100 points, it loses heavily on its lack of international students and faculty.

IIT Delhi director V. Ramgopal Rao said the reason there are so few international undergraduate students (there are some at postgraduate level) is that it is so hard for foreigners to crack what he called “the most difficult admission exam on the planet”.

What’s behind the success of Indian tech CEOs in Silicon Valley?

While IIT holds entrance exams in centres like Dubai and Singapore, foreign students have a “big disadvantage in that they haven’t attended an Indian school and completed the rigorous curriculum”, said Rao. In fact, IIT Delhi has only ever had one foreign student passing the entrance exam – a Korean who went to an Indian high school.

The lack of international faculty is because the pay is so low at the government-funded institution said Rao, who earns US$60,000 a year as the equivalent of a university president while MIT’s president earned US$1.25 million in 2018. An IIT assistant professor gets around US$25,000 annually.

But despite IIT’s global standing, IITians, as they’re known, have a golden reputation and are hired by the world’s biggest corporations on substantial pay packages.

“The brand remains impeccable in terms of what it can do to your resume,” said Chetan Bhagat, a banker-turned-top-selling Indian novelist who graduated from IIT.

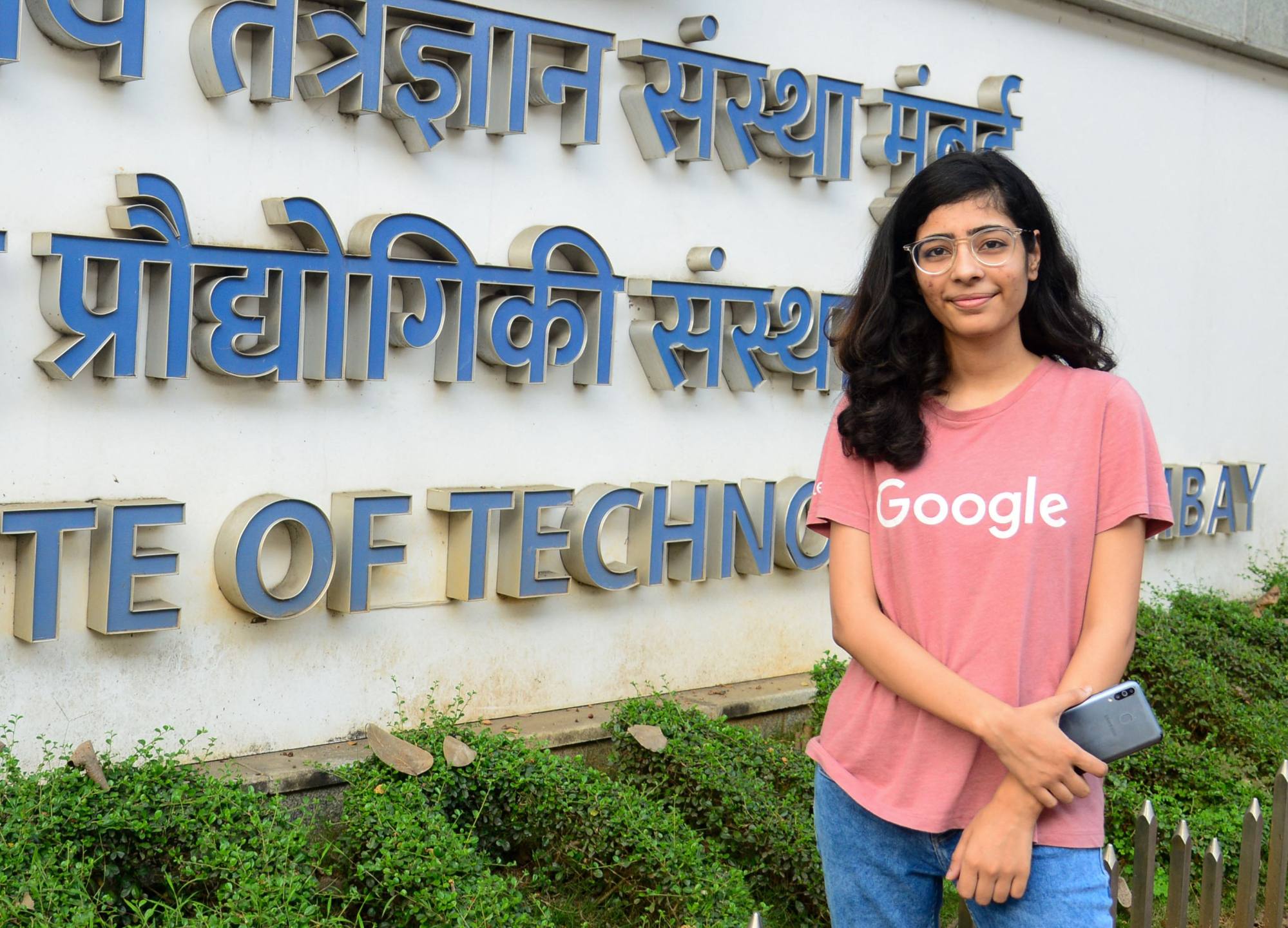

Top 2021 recruiters included Microsoft, Qualcomm, Google, Airbus and Amazon which were looking for graduates in product and software engineering, R&D, financial analysis, data science and other fields. This year, a 22-year-old IIT graduate got a US$263,000 software-engineering job offer from Uber.

‘Mother of all entrance exams’

So what is the special sauce that makes IIT graduates so sought-after? First, there’s the “mother of all entrance exams” that weeds out all but the smartest. The curriculum also places heavy emphasis on creating a solid foundation in mathematics “which helps develop the students’ analytical skills”, said Rao. Students learn how to brainstorm on projects, convert theory into practice, and team-building skills.

Ambitious parents set their sights on IIT for their sons (students are still mainly male though 20 per cent of seats are now set aside for women). Even if their child has no interest in engineering, an IIT degree is seen as an automatic passport to boundless high-paying career opportunities.

“Put Harvard, MIT and Princeton together and you begin to get an idea of the status of this school in India,” said CBS host Leslie Stahl in a 2003 TV programme about IIT, a remark that still holds true.

It’s not easy to become an IIT student, and it’s even tougher to survive this gruelling programme

There are a number of costly “cram centres” involving brute rote-learning of physics, chemistry and mathematics.

“As a teenager, you have to forget about your life for three to four years, you have to forget about the rest of the world, extracurricular activities, and just prepare hard, but you’re compensated once you’re in because you’re studying with the very best,” said Vipul Singh, 32, who attended IIT and is co-founder and chief executive of drone firm Aarav Unmanned Systems.

In 2020, 1,118,673 IIT hopefuls sat the six-hour Joint Entrance Exam. Of those, 150,838 made the cut to appear for the advanced exam. Just 43,204 qualified for entrance. But that was not the end of the road. Students then competed for 13,000 places based on an all-India marking rank and demand for particular engineering, physical science or architecture courses.

Who is Parag Agrawal, Twitter’s new Indian-American CEO?

The competition does not end when the student finally gains a coveted IIT place. “The students are graded relatively, respective to each other. We ask them to compete with each other. That leads them to be the best in whatever they do,” said Rao. “It’s not easy to become an IIT student, and it’s even tougher to survive this gruelling programme, but if you talk to people who’ve made it through, they tell you everything afterwards is a cakewalk.”

Of course, such intense academic pressure and the desire to achieve high marks to make their parents happy can be too much for students’ mental health. “We’ve got a very extensive process, multiple counsellors, ways to identify those lagging behind, to provide them support,” Rao said.

But some still slip through the cracks. In 2019, the government said 50 IIT students had killed themselves in the previous five years. In India, exam-related pressure and the crippling fear of failure results in a tragically high number of student suicides, with the National Crimes Register Bureau saying over 170,000 students of all ages died by suicide between 1995 and 2019.

Alumni network

Back before the tech scene began seriously gaining traction in the early 2000s, there was a huge exodus of IIT talent to the US and to Silicon Valley in particular, in what was seen as a lamentable “brain drain”.

Now, though, IIT graduates are far more likely to stay in India where opportunities are deemed bigger and better. The number of tech start-ups has rocketed. Rao said 20 years ago “80 per cent of the BTech class used to go abroad. But last year, less than 200 of 10,000 IIT graduates went abroad for jobs”.

Kunal Bahl, co-founder of e-commerce company Snapdeal, said in September there had been 4,079 start-ups founded in India by IIT graduates, including 593 by graduates of IIT Delhi and 529 by IIT Bombay alumni.

According to UK accounting software firm Sage, IIT is ranked fourth globally for educating students who have proceeded to create unicorns (start-ups valued at over US$1 billion).

Is India the new China for unicorns and start-up investors?

Graduates wanting to start their own businesses find support through those who have passed through IIT.

“The alumni network is very, very strong, they come and mentor students, they’re contact points for students, they bring their knowledge,” said Aarav Unmanned Systems’ Singh. A number of the graduates who prospered become “angel investors” in ventures launched by other IITians.

“Working with someone who’s also gone to IIT means we speak the same language,” said one investor, an IIT graduate who did not want his name used but said he had invested in six start-ups involving IIT alumni. And if they do not become entrepreneurs, a number of graduates go on to become top Indian civil servants.

Many of the IITians who have done well also contribute heavily to their alma mater. “In the last three months alone, we [IIT Delhi] have received pledges of US$12-13 million. That’s the kind of connection everybody has with each other and with this institution. They either contribute back in mentoring or donate funds,” said Rao.

“All of this creates an extremely vibrant atmosphere.”