Advertisement

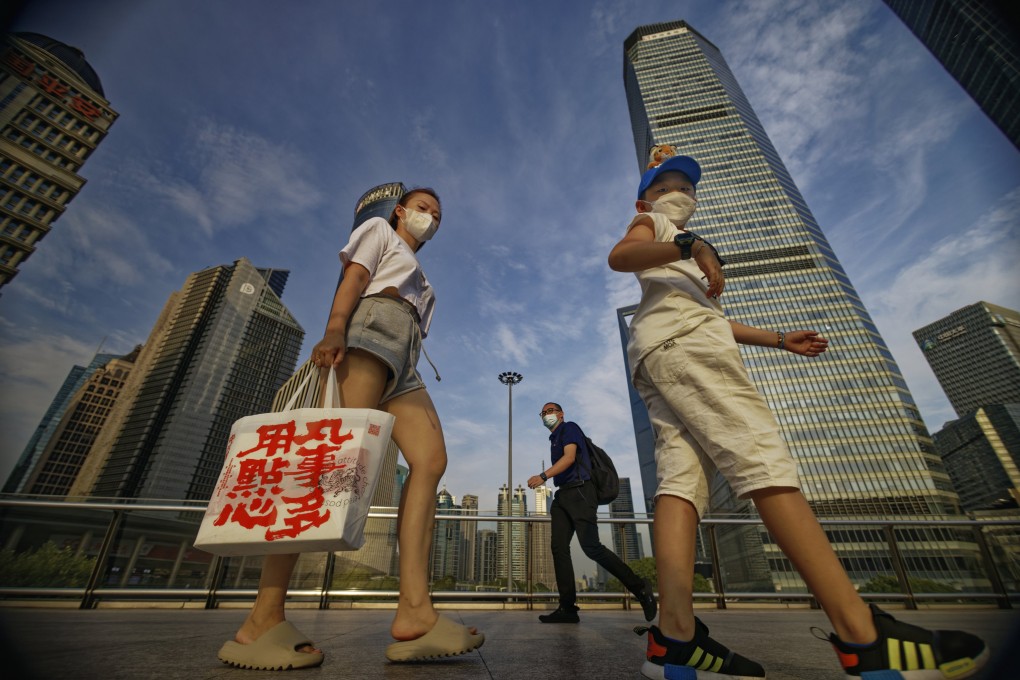

China’s zero-Covid economic drag could be ‘significantly bad’ for Asia: IMF

- The IMF said China’s economy has been affected by it’s zero-Covid policy, and a growing real estate crisis

- The financial institution said Asia would feel the pinch of China’s muted economic growth due to the connectivity of trade in the region

Reading Time:3 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

10

Dewey Simin Singapore

China’s “sharp and uncharacteristic” economic slowdown could spell trouble for its Asian neighbours with whom it has strong trade and financial ties, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) said on Friday, offering a bleak outlook for the region’s economy.

The IMF shaved its growth forecast for Asia to 4 per cent this year, down 0.9 percentage points from an earlier projection, citing in its Asia-Pacific regional economic outlook report that countries also had to navigate tighter global financial conditions and inflation stemming from the war in Ukraine.

While Asia’s economies were expected to expand by 4.3 per cent in 2023, Krishna Srinivasan, director of IMF’s Asia-Pacific department, warned that growth could be lower if the headwinds intensified.

Advertisement

“That’s the kind of risk you’re dealing with,” he told This Week In Asia in an interview on the sidelines of the report launch on Friday.

Srinivasan said China’s economy has been hurt in part by its hardline zero-Covid strategy that involved strict border controls and intermittent lockdowns though he was optimistic that there could be some relief soon.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x