Filipinos slam Marcos’ sovereign fund idea amid fears it could end up like Malaysia’s 1MDB

- The president wants the ‘Maharlika Investments Fund’ set up with seed money from state and private pension funds; there is a lot of anger against the idea

- But amid worries fund may be used by Marcos and associates to launder money in 1MDB-type embezzlement scandal, some say it may help attract foreign investors

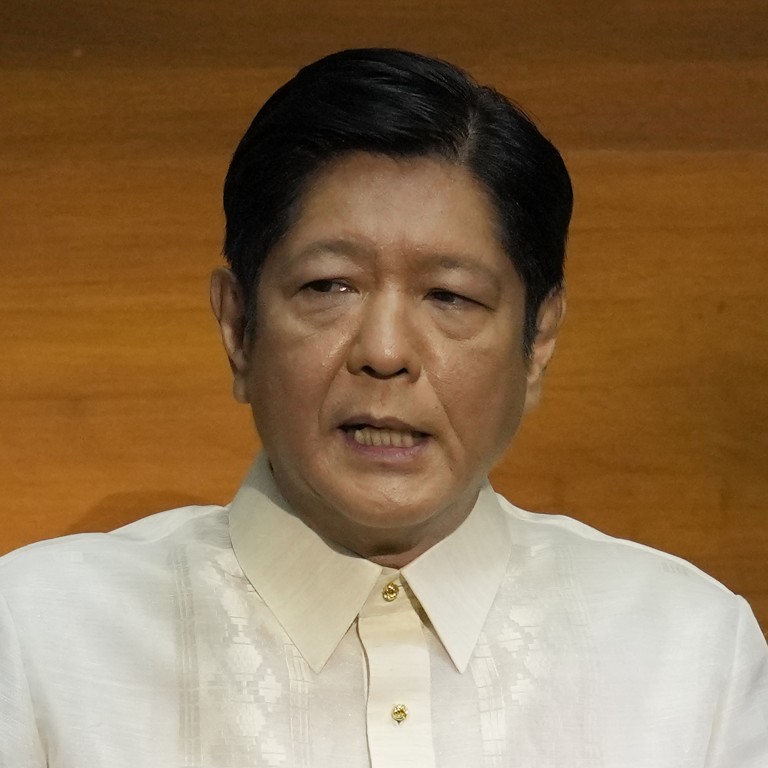

Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jnr’s order for lawmakers to set up a sovereign wealth fund seeded by the pension funds of private and state employees has generated public opposition, with protests planned across the week and a petition against the move drawing some 25,000 signatures.

The fund was recently proposed by three lawmakers related to Marcos Jnr – his cousin, House Speaker Ferdinand Martin Romualdez, his cousin’s wife Yedda Marie Romualdez and his eldest son Ferdinand “Sandro” Alexander Marcos.

“The order came from the President,” said Congressman Joey Salceda, vice-chairman of the House committee on banks and a former research analyst at Ing Barings, speaking on December 1.

Salceda also said he was “nervous” about a particular section in the legislation that barred lower courts from stopping the fund’s investments, leaving that power only to the Supreme Court and the Court of Appeals.

“That’s nerve-racking,” he said. “It’s as if we are hiding something. There’s gossip going around that Marcos' wealth will be reinjected by participation in the Maharlika [Fund]. That’s the rumour,” he added.

Philippines’ Marcos Jnr pitches US investors, unlike pro-China Duterte

The passage of House Bill 6398 has moved “with lightning speed”, reported the Philippine Daily Inquirer newspaper on December 5. Filed on November 28 and approved in principle the next day by the committee on banks, the measure could in theory breeze through the House of Representatives this week.

However, the public outcry might have an impact. An online petition started on December 1 by De La Salle University professor David Michael San Juan has gathered close to 25,000 signatures. Other critics are planning to stage street protests this week.

On Monday, a dozen business associations including the Makati Business Club and the Management Association of the Philippines, as well as economic policy groups, issued a joint statement expressing “serious concerns and reservations” against the proposed fund.

These included the forced participation of pension funds, saying their current actuarial life of 40 to 43 years was already far below the ideal 70 years. Diversion to the MIF would likely further shorten this.

Separately George Barcelon, president of the Philippine Chamber of Commerce and Industry, urged a further review to ensure “such action will not affect our presently good credit standing, which provides us lower foreign loans”.

Writer-historian Manolo Quezon – the grandson of Philippine president Manuel L. Quezon, in office 1935-1944 – said there was chatter within diplomatic circles as early as May, when Marcos Jnr won the election, that he would create a fund. Some diplomats speculated that “it might allow repatriation of [the Marcos] wealth abroad”.

“Repatriation” refers to the still unrecovered ill-gotten wealth of the Marcoses which the late President Corazon Aquino (in office 1986-1992) estimated at US$10 billion. Only a fraction has been recovered, through court litigations and out-of-court settlements.

The possibility of the proposed fund serving as a money-laundering channel could be avoided by imposing “restrictions on who can and can’t buy” the bonds that the board of the Maharlika Investments Corporation would issue, a foreign bank executive told the South China Morning Post, on condition of anonymity.

Under the bill, which would create the Maharlika Investments Corporation, its board would have the power to “approve the issuance of debt and debt-like instruments”. No restriction is imposed on who the buyers are.

The banker had “obvious misgivings about who is pushing for the fund” adding that “the other issue I might have is how the fund will be funded”, since most sovereign wealth funds use excess state revenue.

In the case of the Maharlika fund, 275 billion pesos (US$4.9 billion) in seed money would be drawn from pension funds held in trust by the government: 125 billion from the Government Service Insurance System (GSIS) for state workers, 50 billion from the Social Security System (SSS) for private employees, 50 billion from the Land Bank (LB), and 25 billion each from the Development Bank of the Philippines (DBP) and the National Treasury.

What does a Marcos Jnr presidency mean for Asean and democracy in the region?

Risk analyst Jonathan Ravelas questioned the duplication of function. “What would the Maharlika fund be able to do that the SSS, GSIS, DBP, LB are not already doing? I would like to think their treasury departments are already working to maximise returns, or at least fulfilling their mandates’ capital preservation,” said Ravelas, the managing director of eManagement for Business and Marketing Services.

However, such a fund is not risk-free, he said, with it “essentially boiling down” to how good the fund manager/s of the MIF is/are. “It could also fail if transparency, controls, check and balances are not established,” Acoba said.

Ravelas agreed that “transparency will be key”, but the bill currently states that the fund could be exempt from state audits and the board would report only to Marcos Jnr, not to Congress.

The proposed legislation would also give the Maharlika board and its appointed fund manager/s much leeway, including investing in unlisted companies.

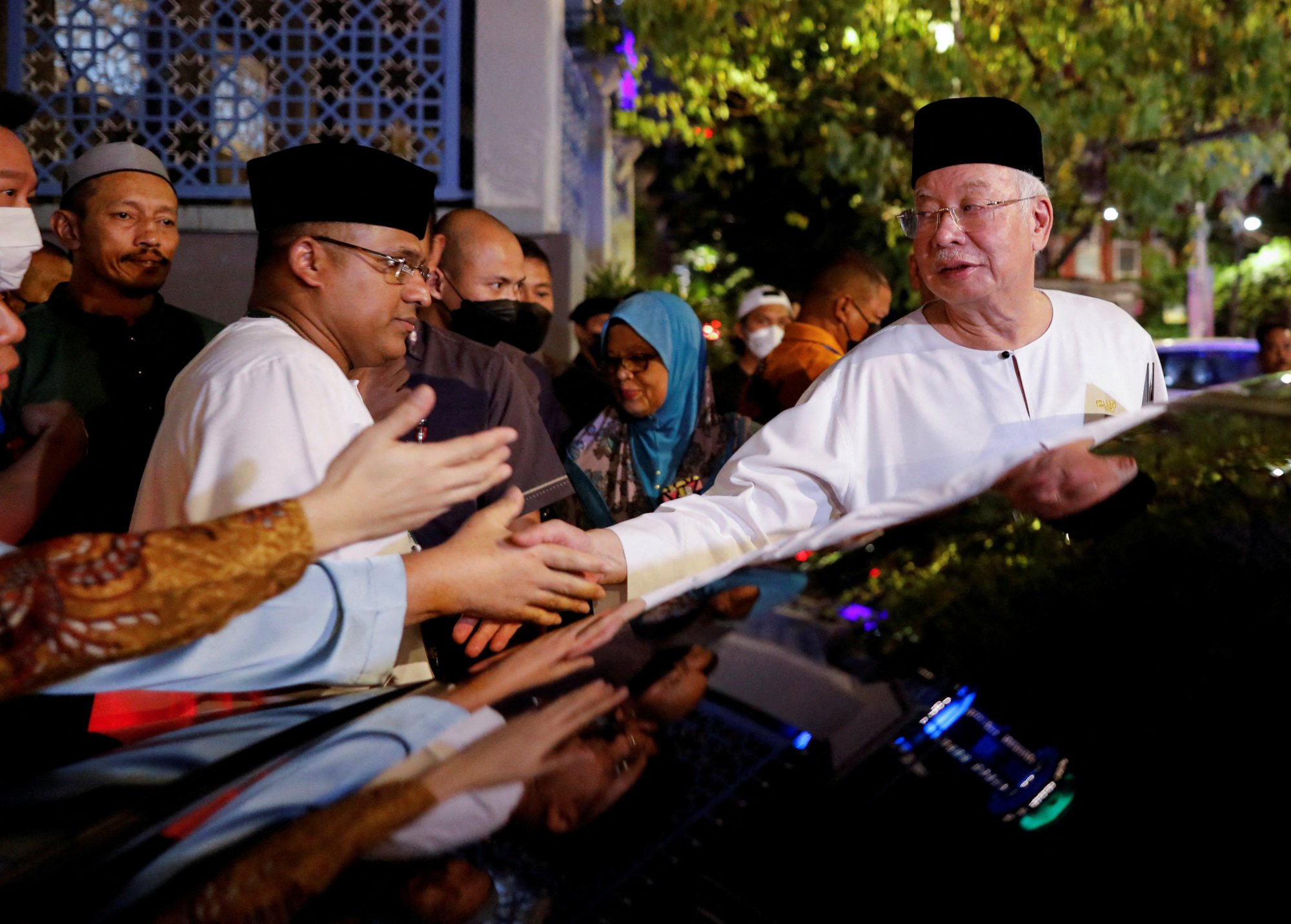

Malaysia’s Najib, Rosmah a step closer to getting back confiscated luxury goods

Corruption and money laundering meant the Malaysian sovereign wealth fund was systematically embezzled, with billions of dollars stolen.

The Philippines is no stranger to large-scale embezzlement. In 1986, after the collapse of the dictatorship of Marcos Jnr’s father Ferdinand, all five entities now set to be tapped for seed money by the dictator’s son were found to be bankrupt, particularly the GSIS.

According to the investigative book Some Are Smarter Than Others by the late scholar Ricardo Manapat, a state audit found that the GSIS – which had accumulated US$1.3 billion from state pensioners by 1980 – had lost US$843 million of that to “investments” in companies owned by Marcos’ associates and questionable transactions.

For instance, when the late Benjamin Romualdez, brother-in-law to the late dictator and father of Speaker Ferdinand Martin Romualdez, became ambassador to China, GSIS funded the formation of the Phil-China Friendship Hotels Corporation with US$26 million to build two luxury hotels, in Beijing and in Guangzhou, according to the Business Day newspaper in 1980. Both hotels failed.

With Malaysia’s Najib behind bars, what’s next for 1MDB justice?

Not all the Marcos family members are on board with a sovereign fund. The president’s senator sister Imee has cautioned against it because “at this time of gargantuan debt and an impending world recession [it] seems heedless and extremely risky”.

She said the country could ill afford to “gamble” with retirement money.

Senate finance committee chair Juan Edgardo Angara has advised further study, since the government will have a deficit of 4.4 billion pesos every day next year, which will have to be financed by debt.

Noted forensic pathologist Raquel Fortun was among many criticising the proposed fund, saying she was considering retiring earlier to ensure she receives her pension.

She said on Twitter that by the time she retired she would have “contributed a huge chunk of my salary” for 37 years. “Painful but necessary deductions, forced savings for my retirement. Then you’ll just take it?”

Meanwhile, opposition senator Risa Hontiveros took exception to the fund’s name “Maharlika”, a word closely associated with Marcos Jnr’s late dictator-father; he founded a bogus World War II guerilla unit called ‘Ang Maharlika’ and unsuccessfully tried to collect back pay for it from the US government.