Can expanded Brics pressure rich nations to fulfil ‘broken’ promises of US$100 billion a year in climate funding?

- Emerging nations say only a fraction of the climate change financing promised by rich nations at a 2009 summit in Copenhagen has flowed to them

- But analysts warn that Brics members must ‘see the opportunity’ to realise potential gains – and not be clandestinely undermined by the US

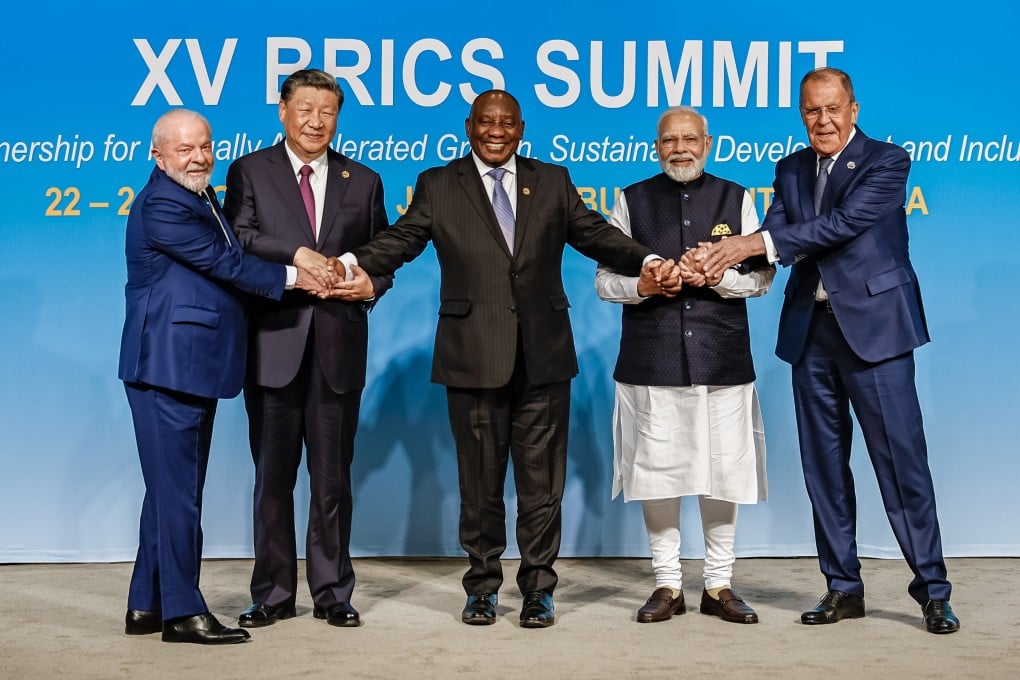

South African President Cyril Ramaphosa, the current Brics chair, announced last week that Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates would become full members of the bloc from January next year.

Brazil, Russia, India and China were the first members, with South Africa joining soon after. Emerging nations say only a fraction of the US$100 billion a year in climate change financing promised by rich nations at a 2009 summit in Copenhagen has flowed to them.

Oxfam International said in a June report that rich nations were three years overdue on their climate financing promise. While donors claim to have mobilised US$83.3 billion this year, the charity said that the real value of their spending was at most US$24.5 billion because this included projects where the climate objectives had been overstated or funds were given in the form of loans and not grants.

“In terms of the broken US$100 billion-a-year climate change mitigation promise, the simple truth is the Global South has previously lacked leverage,” said Einar Tangen, a senior fellow at the Taihe Institute think tank in Beijing.

“Separated like grains of sand, they have been no match for the developed powers.”

The Global South, a grouping of developing and least developed countries, is generally seen to encompass Brazil, India, Indonesia and China, alongside other low- and middle-income non-Western nations.