Explainer | How India and China’s deadliest clash in decades came about

- No shots were fired but a serious physical confrontation between troops left at least 20 Indian soldiers dead with more casualties on both sides

- Beijing’s foreign ministry says the situation is stable, India’s defence minister has mourned the deaths but nationalist sentiment online is raging

At least 20 Indian soldiers have died, with more reportedly injured. Indian media say there are 35 Chinese casualties but Beijing has not confirmed if any of its troops were killed or injured.

The editor-in-chief of the hawkish Global Times Hu Xijin tweeted on Tuesday night that China was remaining silent on the numbers as an act of “goodwill” so that there would be no comparison of deaths that could inflame nationalist sentiments.

‘20 Indian soldiers killed’ in border clash with Chinese troops

India’s Defence Minister Rajnath Singh was the first government minister on either side to address the issue in a statement on Wednesday afternoon, when he described the incident as “deeply disturbing and painful”.

“Our soldiers displayed exemplary courage and valour in the line of duty and sacrificed their lives in the highest traditions of the Indian Army. The nation will never forget their bravery and sacrifice,” he said.

The fatalities were the first in more than four decades from the simmering conflict along the 3,488-km undemarcated border known as the Line of Actual Control.

But many Indian observers said the latest stand-off was unusual, pointing to the size of the troop build-up by China, how they were massing in areas that had previously not been under dispute and the level of violence in brawls between soldiers – with one incident that took place in the Indian state of Sikkim on May 9 leaving several men injured.

Monday’s clash took place in the Galwan Valley, which India accused Chinese troops of entering even though it was not under dispute.

On Tuesday, a senior Chinese military official Zhang Shuili insisted the valley had “historically belonged” to China and said Indian troops had “violated the mutual consensus reached by both countries on border issues”.

Indian foreign ministry spokesman Anurag Srivastava said the incident arose from “an attempt by the Chinese side to unilaterally change the status quo” on the border.

Alongside a spike in domestic coronavirus cases and fears of a second wave of infections abroad, the clash has served to dampen Indian market sentiment, while dominating media headlines and fuelling anger on social media.

Official Chinese media have downplayed or ignored the incident in line with Beijing’s low-key response, but other outlets have reported extensively on Monday’s clash, leading to inflamed and nationalistic sentiments among Chinese netizens.

02:02

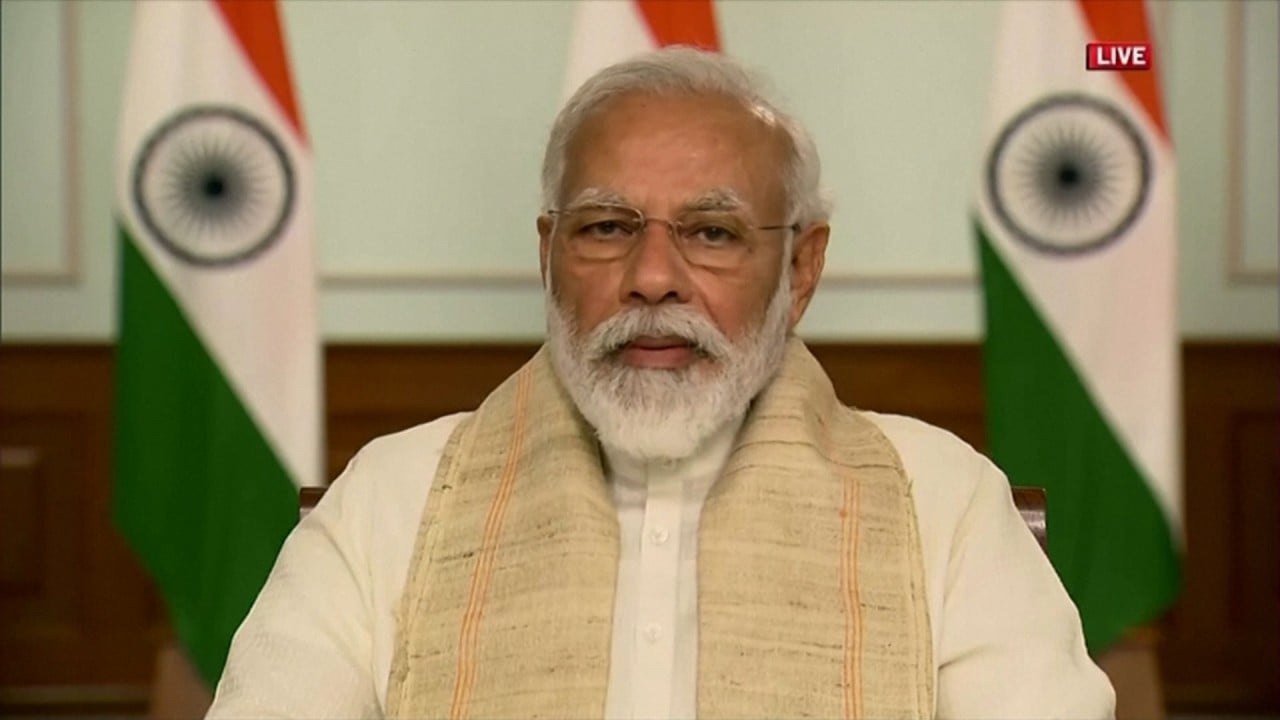

Modi says India wants peace with China, but will provide ‘appropriate response’ if provoked

How did we get here?

Beijing claims about 90,000 square kilometres of territory, comprising almost all of India’s Arunachal Pradesh state.

In 1959, when India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru went to Beijing, he questioned the boundaries shown on official Chinese maps, prompting Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai to reply that his government did not accept the colonial frontier.

In 1962, Chinese troops swarmed the disputed frontier with India during a row over the border’s demarcation. It sparked a four-week war that left thousands dead on the Indian side before China’s forces withdrew.

Beijing retained Aksai Chin, a strategic corridor linking Tibet to western China. India still claims the entire Aksai Chin region as its own, as well as the nearby China-controlled Shaksgam valley in northern Kashmir.

Another flashpoint has been Nathu La, a high mountain pass in India’s northeastern Sikkim state that is sandwiched between Bhutan, Chinese-ruled Tibet and Nepal.

During a series of clashes in 1967, which included the exchange of artillery fire, New Delhi said some 80 Indian soldiers died and counted up to 400 Chinese casualties.

In 1975, shots were reportedly fired across the official border at Tulung La in Arunachal Pradesh. Four Indian soldiers were ambushed and their deaths marked the last time anyone was known to have been killed in the long-running dispute until now. Then, Delhi blamed Beijing for crossing into Indian territory, a claim dismissed by China.

The Doklam plateau is strategically significant as it gives China access to the so-called “chicken’s neck” – a thin strip of land connecting India’s northeastern states with the rest of the country.

It is claimed by both China and Bhutan, an ally of India. The issue was resolved after talks. In 2018, India said Chinese troops advanced around 300-400 metres inside the Demchok area and pitched five tents. Three were later removed after talks between the two armies.

What has been done to ease tensions?

Since 1993, India and China have signed several bilateral agreements and held more than 20 rounds of border talks to maintain peace.

The current stand-off is thought to have been triggered by India’s construction of a road in the Galwan Valley, its latest project in years of infrastructure build-up by both sides in the border region.

In the days that followed, the Indian establishment indicated through leaks to the media that troops from both sides would disengage in some areas while officials would continue talks to ease the situation.

Last week, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying said Beijing had reached a “positive consensus” with Delhi.

But respected former Indian Army colonel Ajai Shukla, in a piece for the Business Standard newspaper last weekend, said there was no indication that Chinese troops were withdrawing. He quoted sources saying that the Chinese military was strengthening its hold on “60-odd square kilometres of disputed territory that it has illegally occupied” and highlighted other areas along the border where Chinese tanks, armoured vehicles and bunkers had been spotted.

No shots have been fired in the current stand-off, with Indian security officials telling various media outlets that the clashes involved soldiers attacking each other with their fists, rocks and clubs.

05:02

Indians burn effigies of Chinese President Xi Jinping over deadly border clash

How bad is it?

Monday’s clash was the deadliest in more than half a century and comes as both India and China are grappling with a rise in domestic nationalism and a series of external challenges.

Beijing, meanwhile, is locked in an ongoing feud with Washington over matters ranging from trade to tech to the origins of the coronavirus pandemic, and is facing pressure from other economies seeking to reduce their dependence on Chinese goods and manufacturing.

But given that India’s military is much smaller than China’s, analysts do not foresee Delhi wanting to escalate the situation.

At a regular press briefing in Beijing on Wednesday, Chinese foreign ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian said troops from both sides were working together to “manage the related situation”.

Michael Kugelman, a South Asia specialist at the Wilson Centre, said the two countries were unlikely to go to war because they cannot “afford a conflict.”

“But let’s be clear: it beggars belief to think that they can magically de-escalate after a deadly exchange with such a higher number of fatalities,” he said. “This crisis isn’t ending any time soon.”

Where do we go from here?

Modi has called for a gathering of all major political parties with parliamentary representation on Friday evening.

This is to consult them on India’s response on the issue and ensure limited opposition to the administration’s plans when they are announced.

Meanwhile, his Bharatiya Janata Party has gone into overdrive with posts on Twitter in support of Modi and maintaining that the “borders of India will remain intact” under his leadership.

The high roads to border conflict through India and China

China’s Global Times, published under the auspices of Communist Party mouthpiece People’s Daily, said in an editorial that India had misjudged Beijing on its will to defend itself against provocation, despite strategic pressure from the US.

It added that if India thought its military was more powerful than China’s then it was wrong.

Cheng Xizhong, visiting professor at China’s Southwest University of Political Science and Law said the current situation was “entirely caused by India”.

“India always miscalculates the situation and always invades Chinese territory when China is in the midst of facing international problems

“It is difficult for us to understand the thinking of Indians. After decades of joint efforts by both sides, China and India have established working mechanisms for maintaining peace and security in the border regions. Currently, there is only one way to resolve the military confrontation peacefully, and that is, for the Indian soldiers to return to where they’ve come from,” Cheng said.

00:49

China-India border region is ‘stable and controllable’, says China

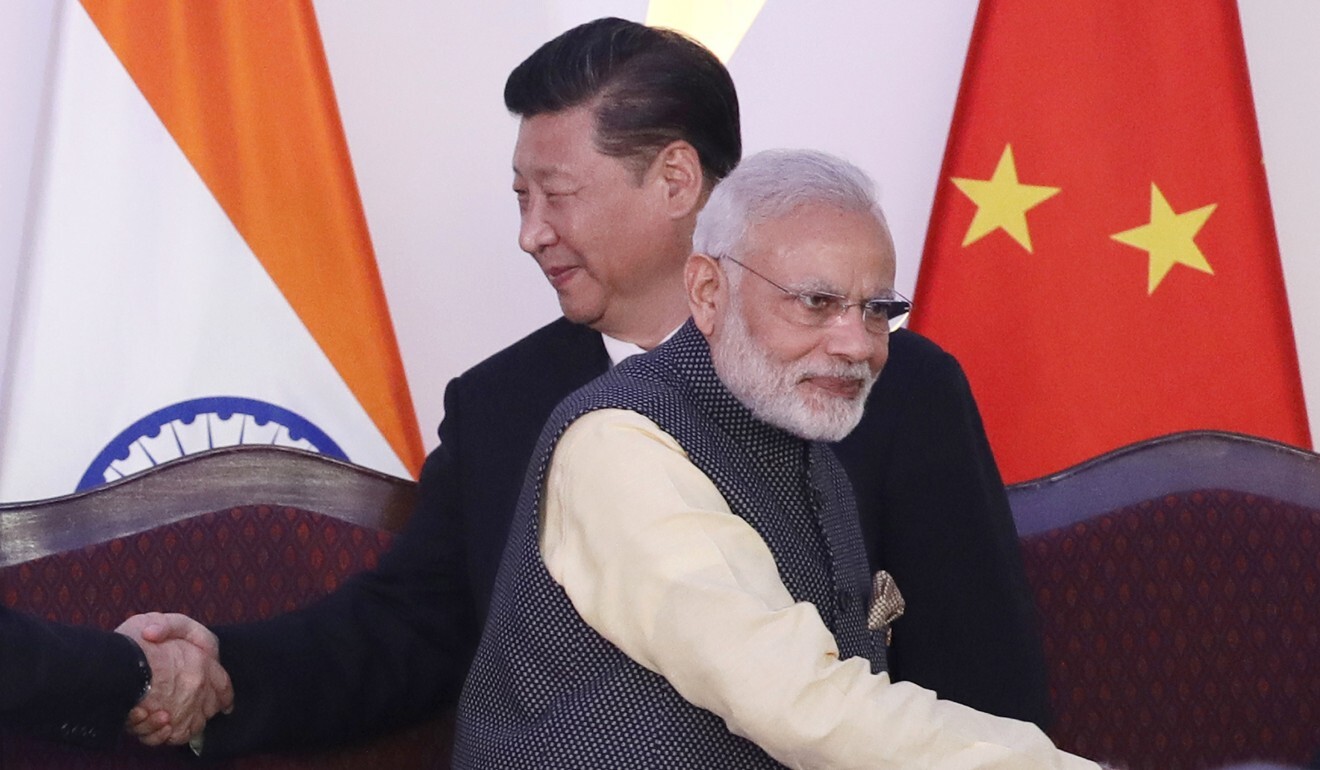

Over the last decade, the world’s two most-populous nations have ramped up trade and people-to-people ties, with Modi and Xi meeting at least 18 times since the former came to power in 2014, in one-on-one meetings and on the sidelines of large-scale summits.

Last year, at their second informal summit in the coastal town of Mamallapuram – after the first one in the Chinese city of Wuhan in 2018 – both men agreed they would host 70 activities to mark 70 years of diplomatic relations this year.

But analysts say this week’s violent conflict means both are entering a period of rocky relations, as they compete for influence in Asia amid the ongoing US-China tussle.

Reporting by Agence France-Presse, Bloomberg, Associated Press, Kunal Purohit, Maria Siow