Explainer | ‘Uniting for Peace’: What to expect from Asia at the UN General Assembly emergency session on Ukraine

- China and India are mulling their options in condemning Russia’s aggression while considering the long-term costs of their response

- Long-standing US allies Japan, South Korea and Australia are expected to take a firmer stance against Russia

The session will involve the participation of all 193 member states. Only 10 such emergency sessions have been held since the UN was formed after World War II.

Russia last week used its veto to block a hastily put together Western-backed Security Council resolution that condemned Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine.

Then, on Sunday, the Security Council took another vote to allow the General Assembly to convene and discuss the matter.

Unlike the Security Council, which can issue legally binding resolutions, authorise sanctions or military operations, the General Assembly has no real power as its decisions are not binding on member states.

Still UN observers say debate at the General Assembly will put across to Russia that a majority of the international community, including some nations that it has traditional close ties with, do not view its aggression as acceptable.

Under a procedure called “Uniting for Peace” and which was first invoked during the Korean war in 1950, veto-wielding members have no powers to block the emergency session.

Out of the 15 Security Council members, 11 voted to convene the emergency session. Russia voted no while China, India and the United Arab Emirates abstained.

What is likely to transpire at tonight’s meeting and what positions will Asia’s movers and shakers – from Indonesia, to India and China – adopt when they address the General Assembly? Here are the key things to note about the emergency session.

What happens during a ‘Uniting for Peace’ resolution?

The resolution to be debated on Monday was tabled by the US and Albania, which are the so-called “pen holders’’ on Ukraine-Russia tensions.

Also known as Resolution 377A(V), the measure allows for General Assembly debate on a matter if there is a lack of unanimity among the five veto-wielding permanent members of the Security Council: the US, China, Russia, Britain and France.

The precedent for such a measure was first set by the US in November 1950, following the Soviet Union’s veto of a Security Council resolution on the Korean war.

Only 10 such emergency special sessions of the General Assembly have been convened so far, according to the UN website, and have previously been invoked by the UN Security Council on matters such as the withdrawal of foreign troops from Afghanistan in 1980.

Following a debate, all countries are expected to vote on a resolution similar to the one that Russia vetoed in the Security Council last week.

While General Assembly resolutions are non-binding, the UN says they are “considered to carry political weight as they express the will of the wider UN membership”.

“By calling for an emergency special session of the General Assembly … [we] have recognised that this is no ordinary moment and that we need to take extraordinary steps to confront this threat to our international system,” said the US ambassador to the UN Linda Thomas-Greenfield said on Sunday.

Nicolas de Riviere, the French ambassador to the UN, added that the special session was a “necessary new step” to put an end to the aggression against Ukraine.

How will representatives from Asia vote?

Monday’s vote invokes memories of the General Assembly’s actions in 2014, in the wake of Russia’s shock invasion and annexation of Ukraine’s Crimean peninsula.

At the time, the General Assembly independently tabled a resolution for debate, avoiding the need to invoke the rare “Uniting for Peace” resolution.

In that vote, 100 UN member states voted in favour of the resolution while 11 – including Russia – voted against it.

Some 58 countries abstained and the remaining 24 were absent.

Dylan Loh, a Singapore foreign policy scholar, said the resolution this time would likely get more votes, a reflection of the “much stronger anti-war, pro-peace signals globally”.

Russia’s aggression, he said, was “qualitatively different” from 2014, as the sheer scale of the present invasion is “much more materially”, in terms of the number of troops and arms involved.

But China and India, which abstained from the Crimean vote, would do the same, he said. Chong Ja Ian, a political scientist at the National University of Singapore, suggested that the two Asian powerhouses would likely be cautious given their closer relations with Russia. India, especially, relies quite heavily on Russian military technology.

Cambodia, Vietnam and Myanmar were also among the abstaintees in 2014. Loh expected those who were in favour of the Crimea resolution – such as Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and South Korea – to vote the same way.

Apart from China and India, Chong said Indonesia would be “quite cautious” too as its air force has some reliance on technology from Moscow.

For the other countries, much would rest on their dependence on Russia as well as the international financial system.

“Those more likely to be hurt by limiting ties with Russia are likely to be quiet. Those who find their hands forced by sanctions may wish to demonstrate that they are compliant,” said Chong.

Long-standing US allies including Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand would possibly be tough on Russia, he suggested.

Singapore, which has strong strategic ties with Washington, would also be keen to underscore the need for respect for the sovereignty of small states.

During the Monday special session, Chong expected representatives from Asia to call for restraint but there would not be a common position, given the region’s diversity and differing interests. Myanmar, he said, would be one to watch.

While the country’s ruling junta – a key client of Moscow’s arms industry – had deemed the Russian invasion as “justified”, its ambassador to the UN is loyal to the rival National Unity Government, Chong said.

Loh said Ukraine’s Western allies are trying to isolate Russia further by showing the strength and weight of international opprobrium of Russian activities. “These are non-binding resolutions but carry important symbolic, moral, and diplomatic weight,” he said.

Ahead of the General Assembly meeting, the 47-state UN Human Rights Council – which commenced a five-week session on Monday – voted on whether to debate the Ukraine crisis.

The vote offered a glimpse of countries’ position on the matter. India and Pakistan abstained from the vote, while Malaysia, Indonesia, Japan and Nepal were among the Asian nations that voted in favour of a debate.

How has Asia responded to the crisis so far?

Among the first countries in the region to impose sanctions on Moscow were Japan and South Korea, with the latter tightening its exports of strategic items such as electronics and semiconductors.

Singapore on Monday confirmed that it would also impose export controls on items “that can be used directly as weapons in Ukraine to inflict harm or to subjugate the Ukrainians”.

Foreign minister Vivian Balakrishnan, describing the invasion as an “unprovoked military invasion of a sovereign state”, said Singapore would also block certain Russian banks and financial transactions connected to Russia, with specific measures to be later announced.

Analysts have earlier suggested that other Asian countries have been more measured in condemning Russia’s aggression as they mull the long-term costs of their response. Particularly, there could be implications of alienating Russia, the world’s second biggest exporter of crude oil. China has also been criticised by the US for standing on the sidelines and not condemning Russia.

But it would get increasingly difficult to remain neutral as global condemnation against Russia’s aggression increases, said Loh, the Singapore foreign policy scholar.

That way, China’s vote during the UN session on Monday would be closely watched as Beijing has “threaded on an extremely fine line between defending their positions on the inviolability of sovereignty and territory while not outrightly condemning or criticising Russia”.

Loh pointed out that the way the crisis has played out has been hyper-socialised, unfolding rapidly on social media rather than on TV screens.

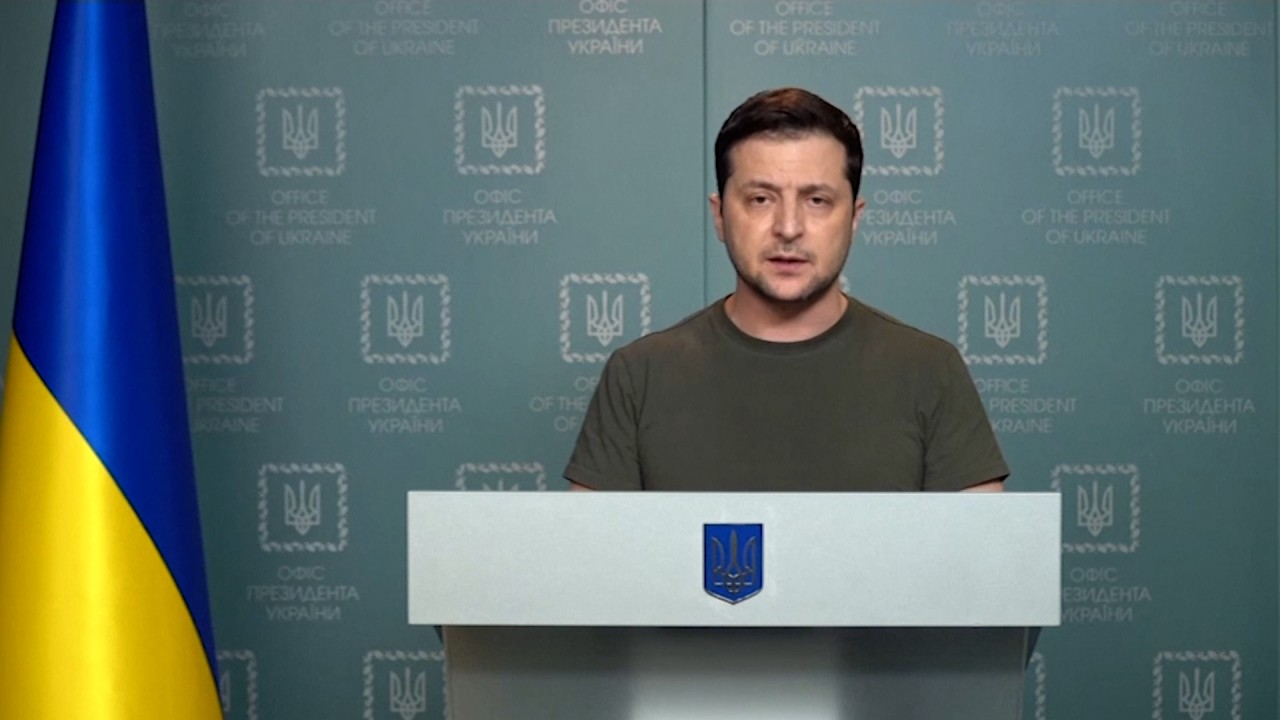

“The first hand, very personal point of view creates representations of warfare that is much more personal, raw and emotive,” he said. “The direct appeals of the Ukrainian President to Ukrainian, Russian and the global audience is instructive. In that regard, this has had the effect of corralling public opinion against Russia and for Ukraine very sharply.”