Explainer | US-China fireworks, Kishida speech, Singapore’s role: key things to know as the Shangri-La Dialogue returns

- The defence meeting, which began in 2002, is up and running again, in person, for the 19th time after a two-year pause because of the pandemic

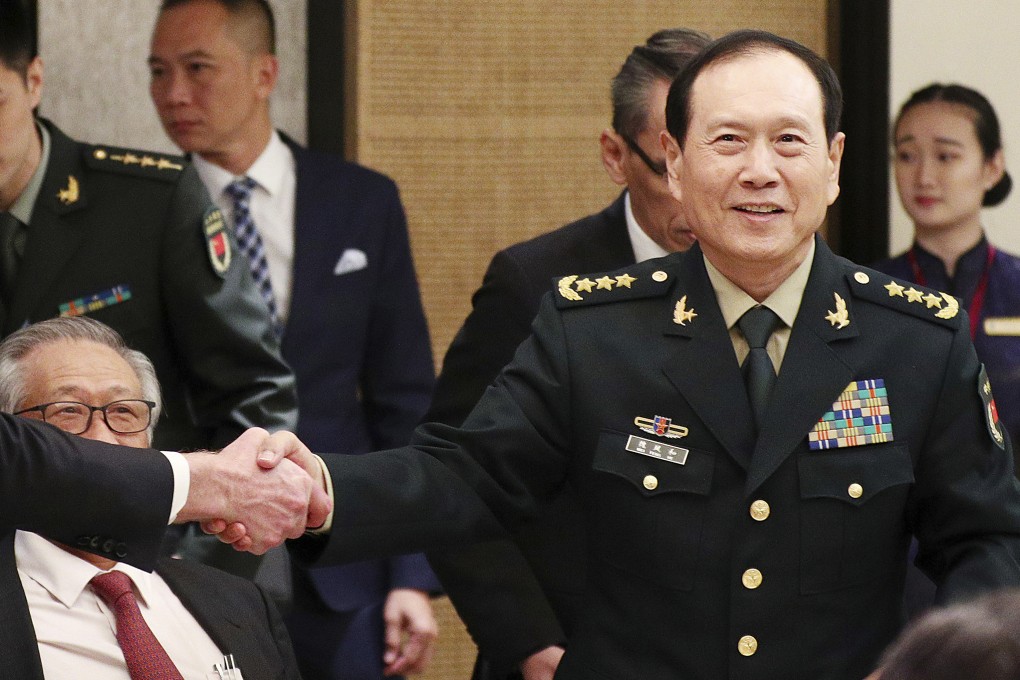

- The event now plays a key role in Asia’s security landscape, with more than 40 countries involved; China’s Defence Minister, General Wei Fenghe, is among those due to give a talk to participants this year

Present at the inaugural session that May were defence officials from 22 countries, including China, Japan, South Korea, India, Australia and Britain.

Since that initial meeting the event has grown in size and influence, now billed as one of Asia’s most important defence dialogues and one which plays a key role in the region’s security landscape.

Robert Gates, the former United States Defence Secretary, said in 2008 that the discussions had “no peer in Asia” while former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, who delivered the keynote address in 2009, called the summit the “pre-eminent” security dialogue in the Asia-Pacific area.

On Friday (June 10), the Shangri-La Dialogue, organised by London-based think tank International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), will be held for the 19th time, having had a two-year hiatus due to the pandemic.

Organisers are expecting around 500 delegates – high ranking military officials, politicians and diplomats – from more than 40 countries, with the war in Ukraine and US-China tensions likely to dominate discussions over three days.