Can Russia and Japan resolve the Kurils territorial dispute?

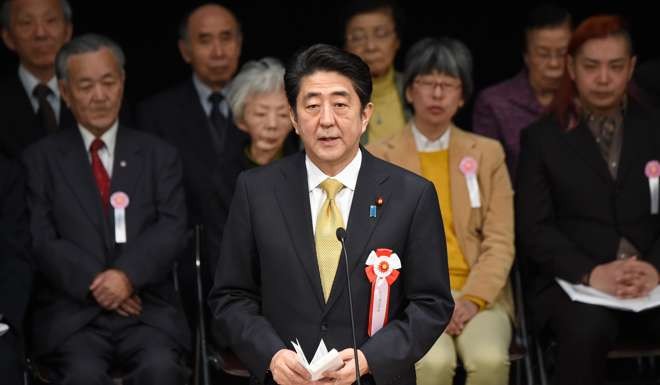

Vladimir Putin and Shinzo Abe embark on a summit meeting today over an issue that has prevented their countries from formally ending second world war hostilities

In his book Romance with the President Vyacheslav Kostikov, the press secretary of President Boris Yeltsin in the 1990s, reminisces that in 1992, “on the eve of his [ultimately cancelled] visit to Japan, the president was so focused on the Japan trip that he seemed unable to talk about anything else”.

“They say you also have a plan on how to deal with the Kuril islands,” he remembers Yeltsin telling him.

“Everyone who comes to my office has a plan...So, what do you have?’ I started to talk about the idea of the lease of political sovereignty over the islands for the period of 50 to 99 years…Russia’s economic rights on the leased territories would be stipulated. Russia would preserve legal sovereignty over them…‘Well, the president sighed. Today you hear all kinds of ideas, don’t you? I attach the number nine to your variant’.”

As Vladimir Putin and Shinzo Abe embark on a summit meeting today, is a No 10 on the cards?

Russia and Japan signed their first treaty defining their border in 1855. Japan got the four South Kuril Islands (it calls them Northern Territories) it is now claiming – Iturup, Kunashir, Shikotan, and the Habomai islets group. Russia got the rest of the Kurils. The territorial status of the Sakhalin Island was left undetermined.