How a 17th-century monk is boosting China-Japan ties

Traveller who spread Buddhist scriptures and gave his name to a classic Japanese appetiser enjoys a renaissance after being championed by Chinese President Xi Jinping

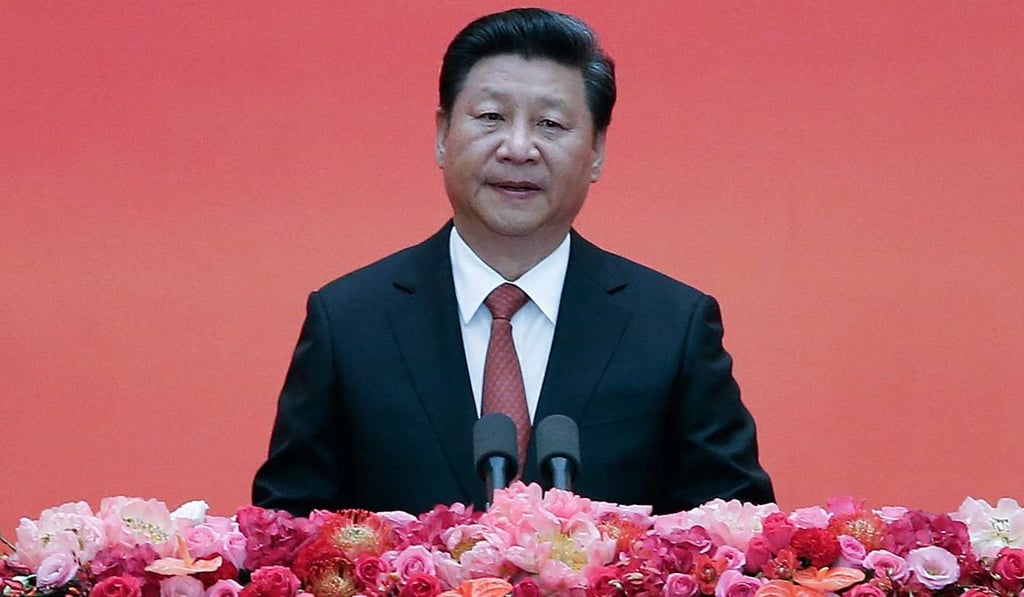

Xi, who came across Ingen’s story while working as a senior official in Fujian province, used the speech to back the idea of people-to-people exchanges between the countries. “During his years in Japan, great master Ingen not only spread the Buddhist scriptures,” Xi explained, “but also brought about advanced culture, science and technology, bringing about a critical impact on economic and social development in Japan under the Edo period.”

Not only did Ingen introduce phaseolus vulgaris or Ingenmame beans to Japan, he also enlightened the country to Ming typefaces and Sencha tea ceremonies.

Ingen’s story dates back to the Edo period of 1603-1867, during which the Tokugawa shogunate, the last feudal Japanese military government, ruled Japan and the city of Nagasaki, to which Ingen travelled. As the only port that had been open to international trading, Nagasaki accommodated numerous Chinese settlers – as much as one-sixth of the city’s population at its peak.

Ingen was born in Fuqing, Fujian province, in 1592. At the age of six, his father went missing, and Ingen grew up travelling to remote cities in search of him, though he never did find him. After returning to his home town and entering the priesthood, he developed Wanfu Temple on Mount Huangbo into a thriving Buddhist centre.