What’s at stake for China as unsure Modi meets unpredictable Trump?

The Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi finds himself at a crossroads in his journey to the West

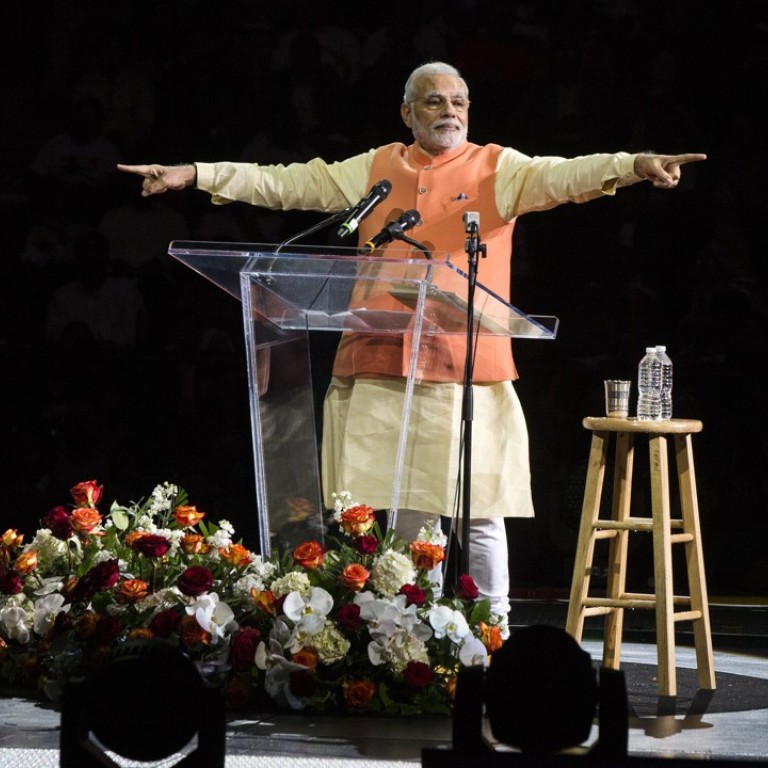

That electric September night three years ago now seems like a distant dream.

Just days before the meeting, Trump singled out India for trying to extract “billions and billions and billions” of dollars in foreign aid to sign up for the Paris climate agreement, drawing an angry response from New Delhi. The strategic and ideological moorings that have anchored US-India relations in the past, such as the Asia pivot and democracy, have clearly loosened, and no one has the faintest on Trump’s position on India. More importantly, if he even has one. More than pressing flesh, Modi’s top priority is to feel out the new White House and find out. This time, there’s just one handshake that matters.

How India and China go to war every day – without firing a single shot

The mood in the Indian media, usually upbeat when it comes to ties with the US, is suitably muted. One headline in the Hindustan Times reads: “Not bromance, this will be more like an awkward first date”, while an opinion piece advises: “India must lower its expectations on the Modi-Trump meet”.

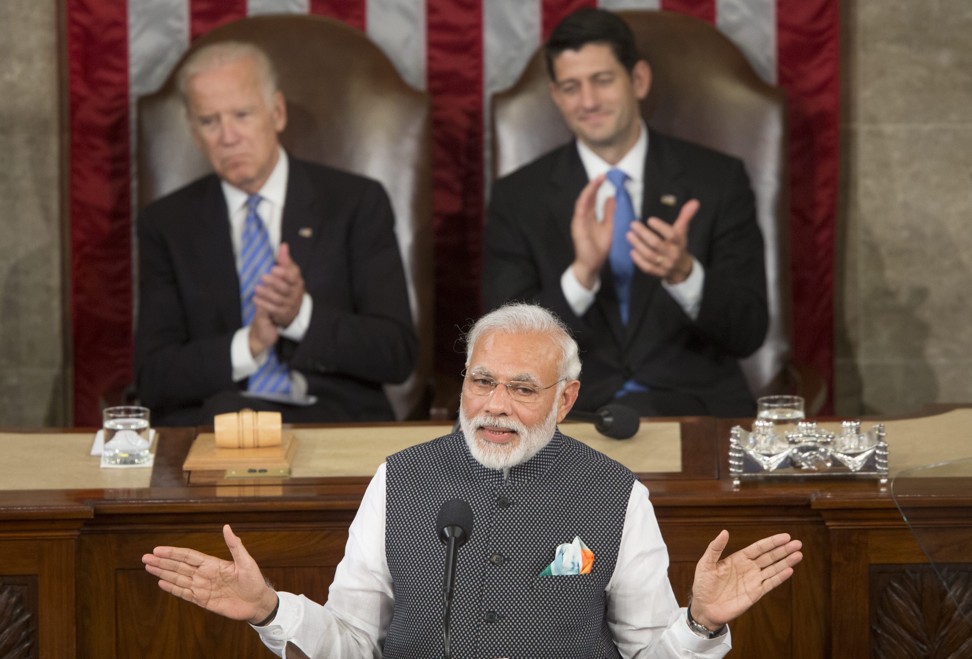

In the last three years, Modi has progressively tightened his embrace of the US, in a departure from the more careful approach of his predecessors. Under him, India has signed a joint strategic vision statement for the Asia-Pacific and the Indian Ocean region, a 10-year Defence Framework Agreement, and a landmark defence logistics pact with the US, giving each side access to the other’s military facilities. Last June, Modi told the US Congress that the US-India relationship had “overcome the hesitations of history”. This June, his uncharacteristic hesitation is writ large on his US trip as he doesn’t know what to expect when he meets the “America First” president who refuses to play by the old rules.

Trump’s indifference is particularly troubling for India, coming as it does when it needs the US the most – to hedge against an assertive China. As Carnegie India director C Raja Mohan put it in a recent talk at the Foreign Correspondents Club of China in Beijing, “The Chinese feel the arc of history is bending in their favour. They don’t have to accommodate others. The way the Asian order is evolving, there will be only one tiger on top of the mountain.”

India and the US have been cultivating one another precisely for such an inflexion point in history. Their relations have hence gone from strength to strength since Bill Clinton’s visit in 2000, propelled by bipartisan support in both countries for closer ties.

“The past 16 years has been a dream come true for New Delhi in some ways,” says Gupta. “But there is a sense in New Delhi that the golden age may be passing, or at minimum fading.”

India’s China policy off target, says Modi’s Mandarin-speaking ‘guided missile’

That puts India in a quandary since it has risked China’s wrath in consciously tilting towards the US in the last couple of years, souring an already difficult relationship between the two neighbours that share a disputed border over which they have fought one war.

“Modi’s foreign policy is too pro-America, especially his security policy, which China is not happy about,” says Lin Minwang, an associate professor at Fudan University. “Before he took office, India seemed content playing swing state between China and the US. But under Modi, it seems India is set to become a ‘quasi-ally’ of the US.”

WATCH: Modi eyes ‘India’s century’ after landslide victory

“The Modi government over-identified with the US’ pivot strategy, which China sees as a project to contain it. Clearly, the Modi-Obama Joint Vision statement of January 2015 regarding Asia-Pacific was completely unnecessary, while differences with China on issues like Pakistan-based terrorists or NSG membership could have been handled discreetly,” says former Indian ambassador M.K. Bhadrakumar.

“The notion of the ‘Dalai Lama card’ was unrealistic too,” he adds, alluding to the view of a section within the Modi administration that the Tibetan spiritual leader’s presence in India gives it leverage and should be used as a diplomatic tool. China protested in unusually strong terms against the Dalai Lama’s visit in April to a territory administered by India and claimed by China, saying India was trying to force its authority on an unsettled area by using the 81-year-old monk.

Why China, India and the Dalai Lama are pushing the boundaries

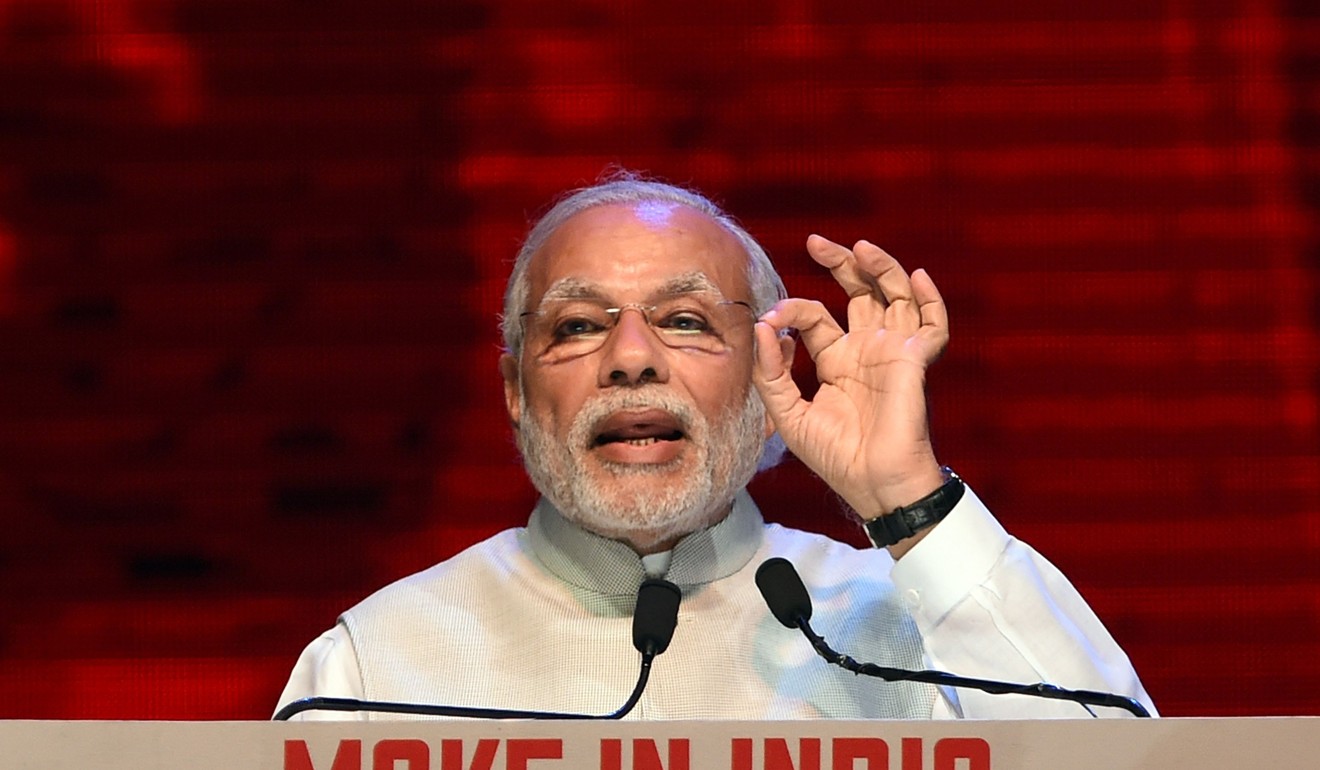

For Modi, who places economics at the centre of his foreign policy, Trump poses a particularly difficult challenge. To address India’s jobless growth problem, he is driving a signature ‘Make in India’ campaign aimed at boosting the underdeveloped manufacturing industry and create 100 million jobs by 2022. But Trump’s campaign promise to bring back manufacturing jobs runs counter to ‘Make in India’, which was in part predicated on wooing to India the same American manufacturers that Trump wants in the US.

India, America’s ninth biggest trading partner, is also among the 16 “cheater” countries that the Trump administration is investigating for unfair practices that give them a surplus over the US in goods trade. The report, due next month, will give the US more ground to put the squeeze on Indian exports. India is in bigger trouble because unlike the others, it also enjoys a trade surplus in services.

It is India’s services sector, especially its mighty IT industry, which is at the highest risk from Trump’s tantrums. Some 67 per cent of this industry’s business is accounted for by the US, making it largely dependent on Washington’s policy on visas and offshoring. Trump has already stiffened the criteria for H-1B visas – non-immigrant visas for temporary workers used heavily by India’s US$130 billion IT sector to fly out inexpensive engineers to the US. Some 75 per cent of the 85,000 H-1B visas awarded annually go to Indians.

He has issued an executive order to review the H1-B allotment process. A reform bill proposes to double the minimum pay for this visa to US$130,000. Indian companies are expected to take a hit as a result, and there are already reports of large-scale job losses across the sector. Indian IT major Infosys has promised to hire 10,000 American workers to take the heat off, but such hiring shifts will come at the cost of the bottom lines Indian IT companies have become used to.

H1-B is supposedly among the topics to be discussed by Trump and Modi. “Trump will likely nod and say polite things to Modi on H1-B but will do nothing about it. Soon there’ll be changes to the H1-B selection process, limiting it only to the most skilled or the highest paid visa petitioners. A whole lot of Indian IT workers will no longer qualify,” says Gupta.

From virtually zero trade links at the turn of the century, China is now India’s second biggest trading partner, after the UAE and ahead of the US. The Modi government has made it much easier for Chinese companies to invest in India by removing some of the red tape. As a result, China has emerged as one of the fastest-growing sources of foreign direct investment into India, from just US$102 million in 2011 to US$4.07 billion last year, with many of its electronics and automobile companies moving production bases to India as wages rise at home. Except Samsung, all four top-selling mobile phone brands in India, for example, are Chinese. The Chinese are also increasingly funding Indian start-ups.

OUTLOOK FOR TRUMP AGE

Dhruva Jaishankar, who manages Brookings India’s activities related to international affairs, sees five possible trajectories of Indo-US-China relations, none particularly good for India. The first is that the US pursues a militarised version of the pivot to Asia while stepping back from commercial engagements. India could be a net beneficiary of this strategically, but not economically. The second scenario is that the US decides to adopt a policy of calculated unpredictability in which conciliatory gestures are interspersed with bellicosity. “India might not like the unpredictability, but nor would others,” Jaishankar says.

“Other scenarios are less encouraging for India. The third is that the US and China broker a deal or power-sharing arrangement that creates realms of influences. Indian interests could become bargaining chips. The fourth scenario is belligerent and militaristic US positions on China not backed up by capabilities, making the US a paper tiger. This increases the chances of miscalculation and conflict.

“Finally, the US and China gets embroiled in a trade and currency war. India will be a loser, given the vulnerabilities of its economy at this juncture.”

What a stronger Modi means for China

Much more deeply rooted than the impulse to balance China with the US is India’s ambition of emerging as a pole in a multipolar world. The end of the Cold War may have put India’s old policy of non-alignment out of fashion, but its civilisational pride and its recent economic success mean it sees a global role for itself as inevitable. Projections that India will be the second largest economy after China within the next two to three decades play heavily on Indian strategic calculations, and the US is seen as an important means of getting there.

In fact, one of the consistent complaints in Indian policy circles against China is that the latter has forsaken its earlier stated goal of a multipolar Asia and has begun to assume the role of a regional hegemon, and is increasingly speaking in terms of a G2 – a bipolar world of the US and China. Trump’s transactional nature, in which the next best deal is better than the last best idea, makes him a particularly risky bet in terms of just such a US-China collusion. Indian strategists are acutely conscious of that risk as China brings a lot more to the table for Trump than India.

“Indians are failing to ask themselves how they can help Trump realise his agenda. They have this habit of always demanding and taking but not ready to give. With a more transactional-minded president like Trump, that can be very damaging,” says Gupta.

Note ban: will it make India, or break Modi?

“Our modest contribution to ‘America First’, a unilateral gesture,” quips Bhadrakumar. “The Modi government is basically hoping for happy days to return in ties with the US. Although the journey increasingly seems hopeless and futile, the foreign-policy compass is set and will not change vis-à-vis the two adversaries – China and Pakistan,” he says.

It is also linked to the exigencies of domestic politics, he adds, as muscular diplomacy appeals to Modi’s core constituency of Hindu nationalism.

But Gupta is not that certain.

“A course correction on China and the US is an option that can’t be discounted, depending on the incentives from China and how far India is pushed by the US,” he says, adding, however, that there would have to be visible course correction for Chinese inducements to flow.

“Modi will first try to glean a first-hand impression of Trump’s wants and inclinations before deciding on making a course correction. Because if so, New Delhi will have to make the first move; Beijing won’t be making it. And retracing one’s steps is always difficult.” ■