As anti-US feeling grows in Cambodia, China cashes in

If it’s business as usual with Washington, as Phnom Penh’s Ministry of Commerce claims, what’s behind Hun Sen’s increasingly fevered rhetoric?

Chinese businesses are quietly expanding their footprint in Cambodia as relations between the Southeast Asian nation and Washington worsen and the din of anti-American sentiment grows louder.

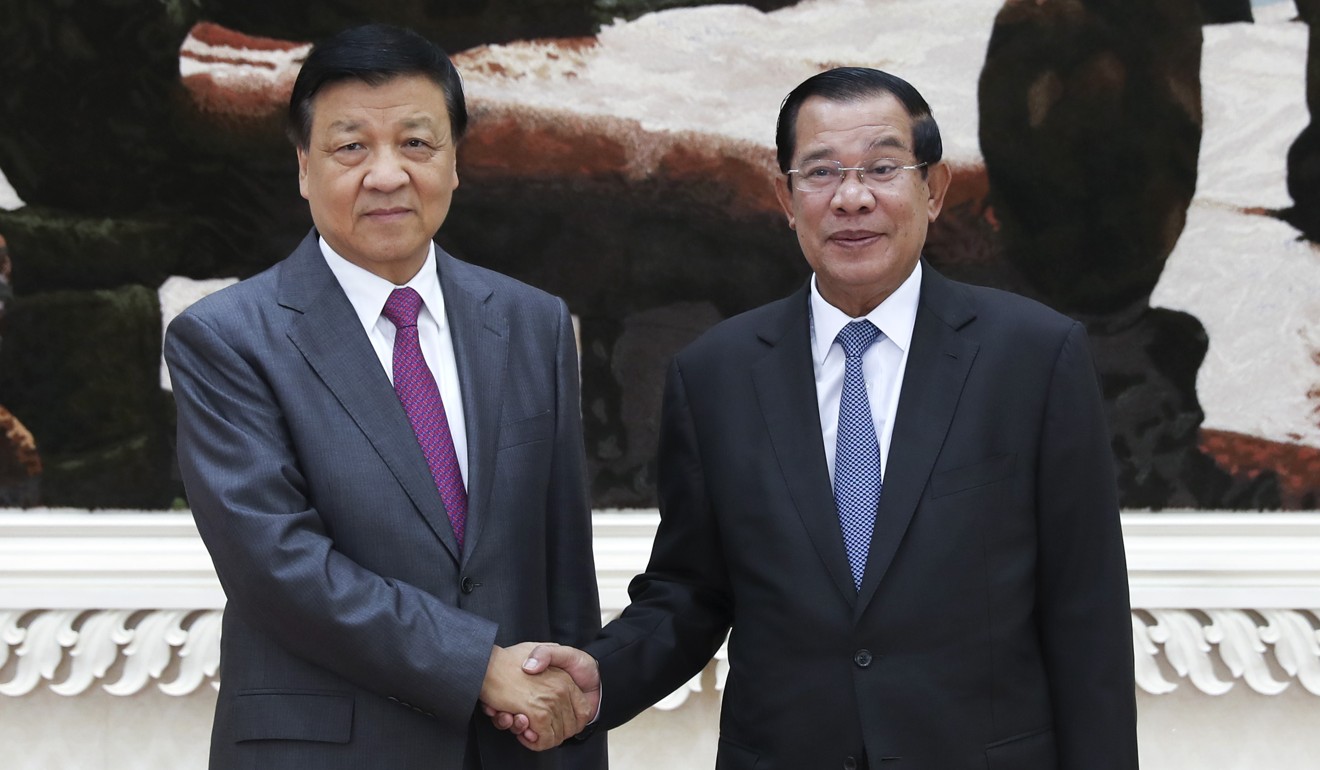

The United States and Cambodia have never been on the best of terms, with the small country’s long-time ruler Hun Sen rarely missing an opportunity to take potshots at the Western superpower.

In recent weeks, the prime minister has unleashed a flood of conspiracy theories centred around the US – often perpetuated by state mouthpiece Fresh News – that claim Washington is promoting insurrection and wants to topple the government led by Hun Sen and the ruling Cambodian People’s Party.

These allegations reached fever pitch when opposition leader Kem Sokha was arrested in early September on charges of treason for what the government says is a US-backed plan to overthrow the government.

In late August, the US imposed visa restrictions on senior foreign ministry officials after Cambodia suspended a controversial 2002 agreement to receive from the US Cambodian deportees who had been convicted of felonies. In response, Hun Sen said Cambodia would no longer help find the remains of American soldiers who had died in Cambodia during the Vietnam war. He also lambasted the US for its role in Cambodia before the Khmer Rouge regime and invited the ambassador to inspect two chemical bombs, which were found in the countryside, as a reminder of America’s past actions.

Hun Sen has also hinted that Peace Corps volunteers should leave the country and suggested the recent mass shooting in Las Vegas was a “mocking of fate” because the US warned its citizens about safety and “anti-American rhetoric” in Cambodia.

US-Cambodia trade relations have been growing in past years, with bilateral trade reaching about US$3 billion in 2016, when nearly 240,000 American tourists visited the country.

More than 21 per cent of Cambodian exports went to the US last year, making the superpower the second-largest importer of garments from the Southeast Asian nation, following the EU.

With so much at stake, the Cambodian Ministry of Commerce insisted business ties between the two countries would not be affected by the diplomatic row.

Soeung Sophary, spokeswoman for the ministry, said: “I think for the business mindset, people do not get scared by [political tensions between the US and Cambodia]. There are many factors that keep them here and assure that the situation will not be getting worse.”

Hun Sen counts on China as he cracks down in Cambodia: has he miscalculated?

Meanwhile, an investment expert speaking on condition of anonymity, said they had not noticed a drop in investment, and those investing in Cambodia would probably not be paying attention to the country’s politics.

“Time and time again, the US has turned a blind eye to human rights issues or stood by Hun Sen because he has brought stability and commerce,” he said.

But not all parties share the same laissez-faire attitude towards American business interests in the kingdom. The US-Asean Business Council has explicitly warned investors of the inherent risks of doing business in Cambodia.

“Certain Cambodian politicians and government officials are more likely now to distance themselves from publicly engaging with US firms until after the July 2018 elections, making government advocacy tougher than it normally would be,” the council wrote in a recent alert to members.

Sophal Ear, professor of diplomacy and world affairs at Occidental College, Los Angeles and co-author of The Hungry Dragon: How China’s Resources Quest is Reshaping the World, also expressed anxiety over the current political climate.

“Elections are usually a bad time for investments anyway, but especially now in Cambodia when there seems to be little recognition for what value Americans, in general, bring to the country,” he said.

Chinese businesses, on the other hand, betray no such anxiety. Chinese investments in Cambodia ballooned by US$200 million last year to US$4.8 billion, making it the single largest investor in the country. A big reason for Beijing’s growing funding is the absence of rights oriented conditions that Cambodia faces when accepting cash from Western countries.

“China doesn’t want a mirror held to its face when it comes to human rights. That’s what criticising human rights would mean,” said Ear.

“With respect to human rights [concerning Cambodia and China], we’re dealing with Dr Evil and Mini-Me. Even with Trump, the US still gives some lip service to human rights.”

In exchange, the Cambodian government often looks the other way for Chinese companies. For example, one Chinese company has development rights over about 20 per cent of Cambodia’s coastline. Rights organisations say a resort development by the firm has led to forced evictions of local residents, sometimes at gunpoint.

End of the road for Indonesia's motorbikes?

Long before Hun Sen called China his country’s “most trustworthy friend”, the two countries’ relationship had been growing at a steady clip. In the 1970s, Beijing backed the deposed King Norodom Sihanouk against the US-backed Lon Nol regime.

Now, China funnels staggering amounts into Cambodia in exchange for loyalty: military uniforms, vehicles, loans for equipment and a training facility in the southern reaches of Cambodia.

In the capital Phnom Penh, Chinese construction projects are popping up everywhere.

And in provincial areas, a host of companies are involved in mining, infrastructure and hydropower industries, among others.

From 2011 to 2015, Chinese firms pumped nearly US$5 billion worth of loans and investment into Cambodia, accounting for about 70 per cent of all industrial investment during that time.

“For a small country, Cambodia garners a disproportionate amount of China’s attention,” Ear said. “It has sold itself as an outpost of China down to promoting a Khmer-language version of [Chinese President] Xi Jinping’s governance book and learning about the judiciary from China, as well as praising Xi’s anti-corruption programme.”

“[It’s about the] South China Sea, undying devotion to Beijing and anti-Americanism, which for Chinese bureaucrats in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is always a plus, because they see the world as zero-sum.

“The enemy of my enemy is my friend.” ■