Trump’s vanishing act: a metaphor for the US in Asia?

The US president’s early departure from the meeting of leaders speaks volumes about his management – or lack thereof – of his foreign policy in East Asia

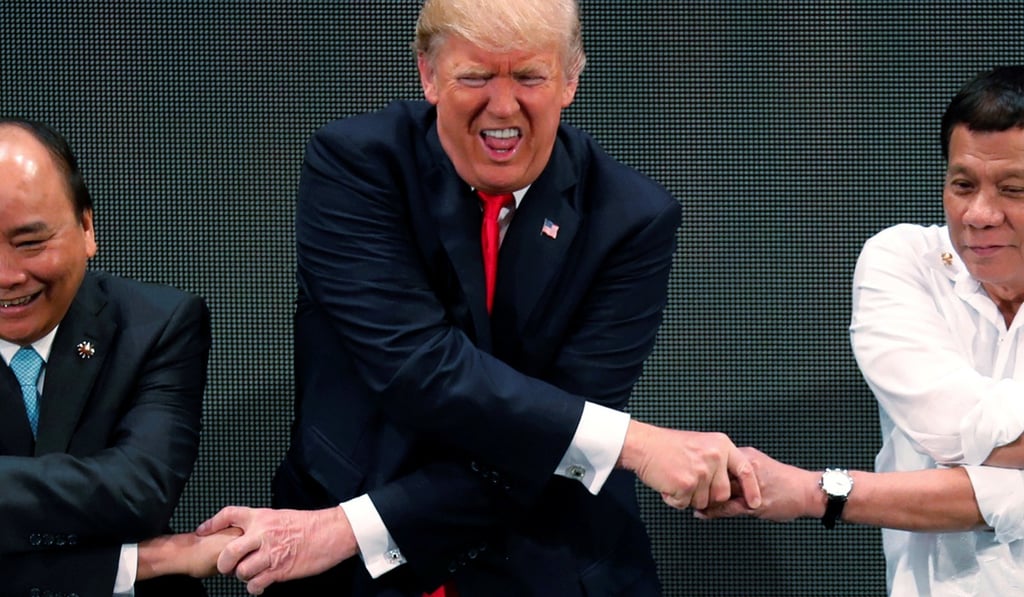

For the past two weeks, a handful of Asia-Pacific countries have rolled out the red carpet for Donald Trump, who completed his first visit to Southeast Asia as the US president while also chalking up a few other “firsts”. Trump attended his first Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation meeting in Da Nang, Vietnam, before heading to Manila for a summit marking 40 years of relations between the US and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations – his first meeting with Asean leaders. He was also expected to attend the East Asia Summit, but only made it as far as a leaders’ luncheon and thus ended his maiden visit to the region on something of a down note.

To recap, Trump had earlier surprised quite a few and disappointed many more when he said he would not attend the East Asia Summit – despite a pledge in April from US vice-president Mike Pence that he would. But Trump subsequently appeared to have averted diplomatic embarrassment for the US as well as Asean by changing his mind and deciding to include the summit on his itinerary. However, the red faces were to return – while Trump managed to join the East Asian leaders for their usual lunch marking the summit, he skipped out before the nitty gritty began, citing scheduling issues.

Trump’s decision not to invest a few additional hours to attend the summit cast a spotlight on the administration’s management – or lack thereof – of its East Asia policy.

The flip-flop suggested a lack of understanding regarding Southeast Asia, adding to a growing sense of uncertainty towards the US in the region, while Trump’s mercurial decision making raised further questions about US credibility and its ability to fulfil commitments.

If the word of the vice-president counts for little, should Trump’s word or that of other senior US officials be taken seriously?