Mahathir Mohamad. Malaysia’s anti-China rebel? Not so fast …

The Chinese bogeyman helped Mahathir get elected, but now he is playing a new game – mending fences after cancelling projects worth US$22 billion. And with a visit to Beijing under his belt, he seems to be winning

Mahathir Mohamad, the anti-China rebel of Southeast Asia?

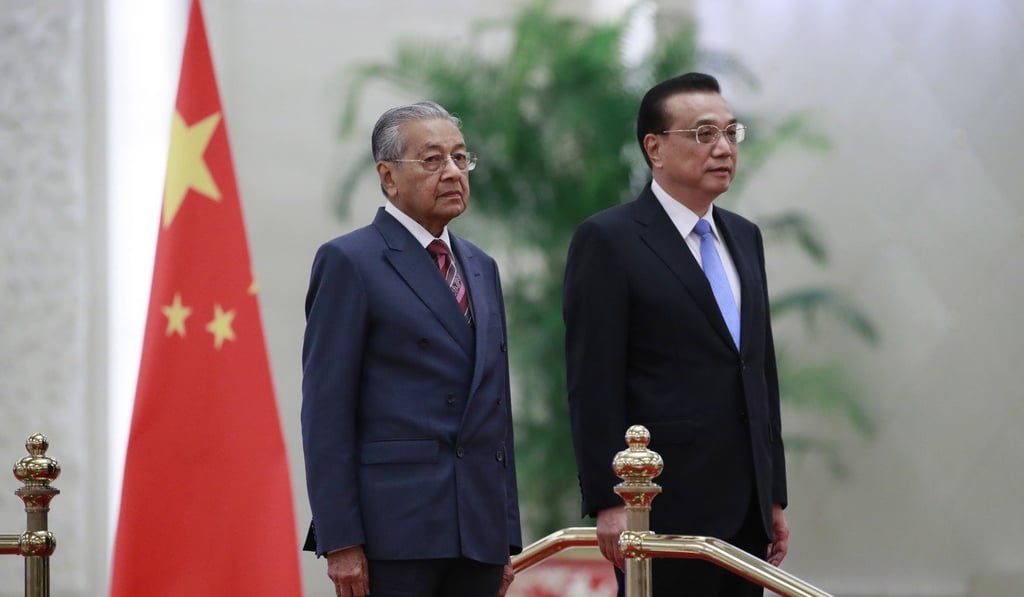

Not quite, if the reaction of foreign-policy observers to the Malaysian leader’s five-day visit to China is anything to go by.

The 93-year-old leader’s trip had attracted intense scrutiny for any residual signs of the anti-Beijing hawkishness he had shown in the run-up to his shock election victory in May.

Close watchers of Malaysia-China ties said the visit had been a success and that both sides had shown an eagerness to “meet halfway” and put behind them the uncertainties that had built since Mahathir defeated his Beijing-friendly predecessor Najib Razak.

And his public position on China before the election had been even more alarming for China’s leaders – at one point during his campaign he blasted his one-time protégé Najib for ceding sovereignty to Beijing.