When Trump opens his arms to Kim again, could they close the door on the Korean war?

- Expectations are growing that the US president and North Korean leader may use a second meeting on denuclearisation to declare a formal end to the 70-year conflict

- Despite the signing of an armistice in 1953, the war officially continues to this day

Christine Ahn, founder of peace activist group Women Cross DMZ, said ending the Korean war could be the US president’s “Nixon moment” – referring to the normalisation of relations with China in 1979 after a historic visit by then-president Richard Nixon seven years earlier.

Is the US about to lower the bar for North Korea denuclearisation?

President Trump is ready to end this war ... We’re not going to invade North Korea

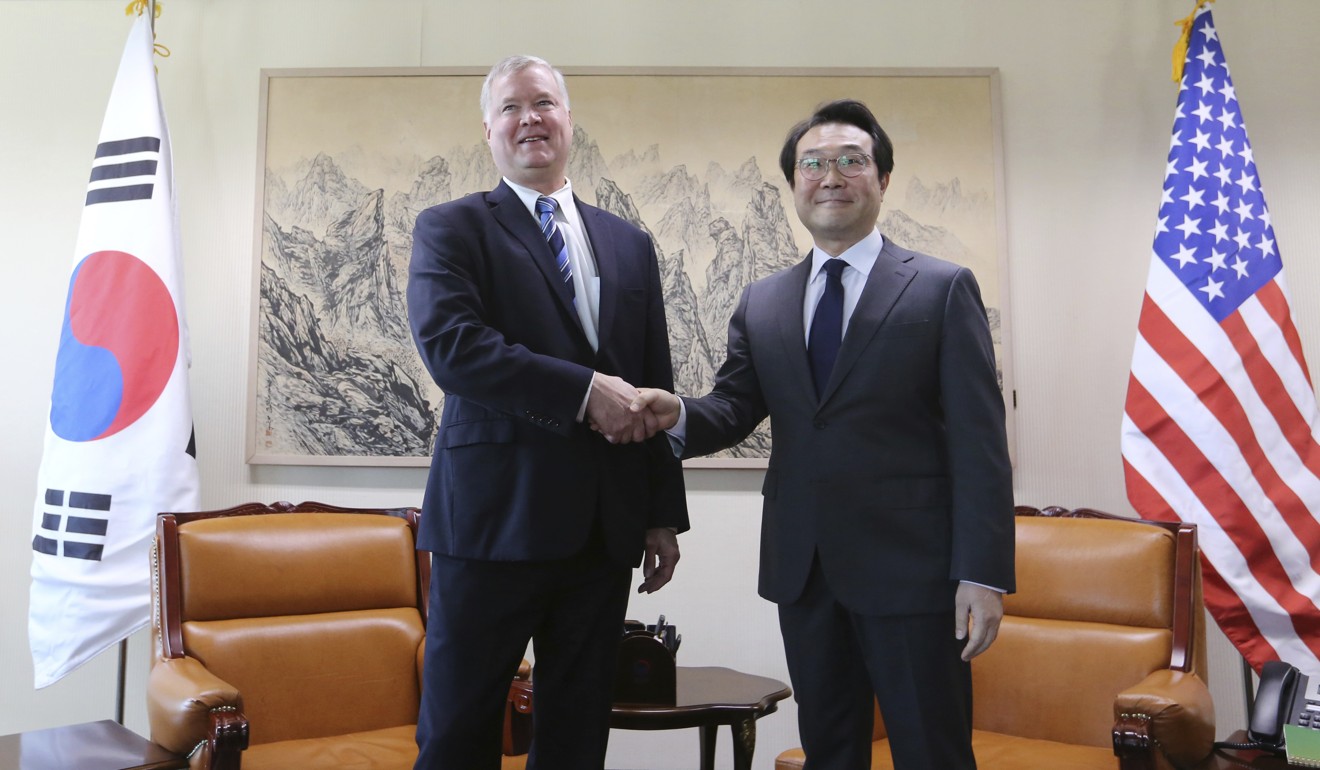

Stephen Biegun, US special envoy for North Korea, last week said Trump was more deeply committed to ending the hostility on the Korean peninsula than any president before him.

“President Trump is ready to end this war,” said Biegun during a speech at Stanford University. “It is over. It is done. We’re not going to invade North Korea. We are not seeking to topple the regime.”

While rich in symbolism, the practical implications of ending the Korean war are open to interpretation. One common expectation of normalising relations is that Washington would open an embassy or liaison office in Pyongyang, and vice versa. An end-of-war declaration could also be accompanied by relief from US sanctions and the easing of a travel ban for US nationals.

More controversially, ending the state of war is seen in some circles as synonymous with the removal of US troops from South Korea, a long-standing demand of Pyongyang. China, which is the North’s main benefactor and has repeatedly expressed its support for a peace deal, would likely welcome a retreat of US forces. Japan, which views North Korea as its main security threat and has been openly sceptical of Trump’s rapprochement efforts, would greet such a development with trepidation.

In South Korea, resentment of refugees from the North

For decades, the North has called on the US to sign a formal peace treaty and end its “hostile policy” against it, viewing the US presence as a security threat and barrier to reunification with the South.

Trump, who has suspended joint military exercises with Seoul as a concession to the North, has repeatedly complained of the cost of stationing troops in South Korea, but on Monday told CBS he had “no plans” for their withdrawal.

“I think that eventually, when we see the final end of the war, when we see that peace prevails on the Korean peninsula, I think we have to ask that question: What is the need for a US military presence?” said Women Cross DMZ’s Ahn.

Almost eight in 10 South Koreans support the signing of a peace agreement with the North, according to an opinion poll carried out by Real Meter last year – although Seoul is not a signatory to the 1953 armistice, unlike Washington and Pyongyang. But most South Koreans also support the continuing presence of US forces in their country; 96 per cent said it was “necessary” in a 2017 survey by the Asan Institute for Policy Studies.

“Most South Koreans want peace,” said Kim Jong-ha, who leads the Graduate School of National Defence and Strategy at Hannam University in Daejeon, South Korea. “However, signing a peace treaty before North Korea has taken any concrete steps to denuclearise is the wrong way.

Could Hong Kong’s ‘one country, two systems’ work for Korea?

“In particular, South Koreans think that North Korea will not give up its nuclear weapons easily, if at all. In this situation, the disadvantages of signing a peace treaty to end the Korean war outweigh any possible benefit.”

Some analysts argue that a peace declaration or treaty – the latter of which would have to pass the high bar of two-thirds support in the US Senate – would be rewarding the North before it had taken concrete steps toward denuclearisation. Although Pyongyang blew up tunnels at a nuclear facility and dismantled a missile test site earlier this year, proliferation specialists have widely downplayed these moves as largely symbolic or reversible.

“A ‘peace agreement’ would disincentivise the Kim regime from taking steps toward dismantling its nuclear arsenal,” said Soo Kim, a former North Korea analyst with the CIA. “Game over, essentially. For Kim, retaining nukes in an atmosphere of peace – namely [easing] sanctions pressure and the gradual withdrawal of US troops from South Korea, the wedge finally splitting the US-ROK alliance – means even more options from the menu of extortions, threats, and realising his ultimate goal of reunifying the two Koreas under the DPRK.”

Although fighting in the Korean war ended nearly 70 years ago, the US and North Korea have no formal diplomatic relations. As a result of crippling sanctions and a travel ban, exchanges of goods and people between the countries are almost non-existent.

Six months after Trump and Kim shook hands, denuclearisation a distant hope

Since the early 1990s, the sides have been at near-constant loggerheads over Pyongyang’s development of nuclear weapons and ballistic missiles, more than once coming close to armed conflict. During the early days of his presidency, Trump reportedly considered launching a limited “bloody nose” strike on the North to thwart its nuclear development.

But more recently, Trump, who electrified the Republican base as a candidate with a platform that railed against military intervention abroad, has made no secret of his desire to bring about a historic leap forward in US-North Korea relations. Among others, some veterans of the “Forgotten War”, which left about 3 million people dead despite having little presence in the public consciousness, have applauded his efforts.

Before his first meeting with Kim, Trump indicated that ending the Korean war could be among the items on the agenda.

“Can you believe that we’re talking about the ending of the Korean war?” Trump said days before the June summit, during which the two sides made a less definitive commitment to “build a lasting and stable peace regime”. “You’re talking about 70 years.”