Advertisement

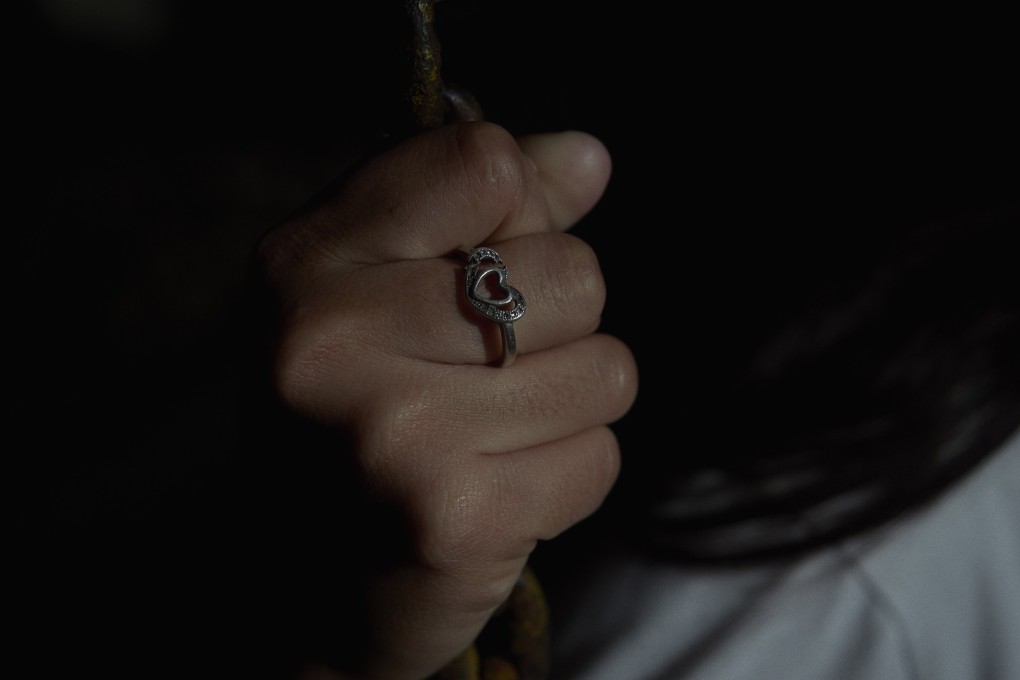

Filipino children abandoned to internet sex abusers during coronavirus

- Online sexual exploitation of children in the Philippines has soared since the outbreak began, while lockdown has robbed them of safe havens

- Shelters are operating at only half capacity, but staff say there is an unofficial policy of keeping their doors closed

Reading Time:5 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

The boy is 16 years old, and law enforcement officers believe he’s being sexually exploited by foreigners over the internet – abuse that seems to have been going on for years. He lives in the Philippines, and they know exactly where, right down to the house where he eats and sleeps and logs online. They have a pretty clear picture of what his abusers are doing to him, and they are worried about what is likely to happen if they don’t get him out fast.

This would normally be the part of the story where a rescue occurs. But the National Bureau of Investigation – a government agency under the Department of Justice – says it is unable to act. Their agents are prepped to approach the teenager, to speak with his family and swiftly remove him from further harm’s way. What they don’t know is what to do with him after that. Government authorities have told them that all of the children’s shelters in Manila are full due to the coronavirus pandemic. Children’s shelters say that no government authorities have reached out to them to ask.

And so the 16-year-old is abandoned to his abusers: unaware of the increasingly frantic dispute over his safety taking place via email and video call across the city, or that anyone is looking out for him at all.

Advertisement

As the rate of Covid-19 infections surpasses 44,000 across the Philippines, the impact of President Rodrigo Duterte’s military-enforced safety protocols is becoming increasingly apparent among the country’s most vulnerable. More than seven million people are currently out of work, and schools remain closed.

In June, the UN’s Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) renewed their call for an “on-the-ground independent, impartial investigation into human rights violations in the Philippines” including police violence during the quarantine, while child rights organisations such as Save the Children, the International Justice Mission and Unicef have been warning of a surge in the online sexual exploitation of Filipino children since the outbreak began. Research shows that girls are the most at risk – a study released by the IJM in May found 86 per cent of victims were female – but boys are frequently targeted too.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x