As Indonesia wavers on deforestation pledge, young climate activists demand action

- Southeast Asia’s largest economy has long struggled between development and conservation, preferring ‘sustainable forest management’ to zero deforestation

- But younger, more vocal activists are demanding more action to fight climate change in the home of the world’s third largest tropical forest

Indonesia, which aims for net zero carbon emissions by 2060, has a turbulent history when it comes to protecting its forests, but recent comments from the environment and forestry minister, Siti Nurbaya Bakar, have still bewildered green activists.

Indonesia, with the third-largest area of tropical forest in the world, had just days before endorsed a legally non-binding pledge during the COP26 climate conference to halt and reverse forest loss and degradation by 2030, alongside 136 other nations. These signatories account for nearly 91 per cent of global tree cover and 85 per cent of the world’s primary tropical forest.

Vice Foreign Minister Mahendra Siregar later told Reuters that the pledge did not contain the phrase “end deforestation” by 2030 and Indonesia had interpreted it as a vow to carry out sustainable forest management. Nevertheless, the outrage to Siti’s tweets came swiftly on social media, including from environmentalists and climate activists.

“We were stunned by her statements, which is quite funny since she is the minister of environment and forestry,” said Nadia Hadad, director of Jakarta-based environmental NGO The Sustainable Madani Foundation. “The development must go on but we can’t allow deforestation as we have a target to become a net carbon sink by 2030.”

According to Nadia, bureaucratic overlaps are one of the major impediments hampering efforts to save Indonesia’s forests, as companies are sometimes able to get permits to clear protected woodland and conservation areas by applying to different government bodies that do not share up-to-date forestry data.

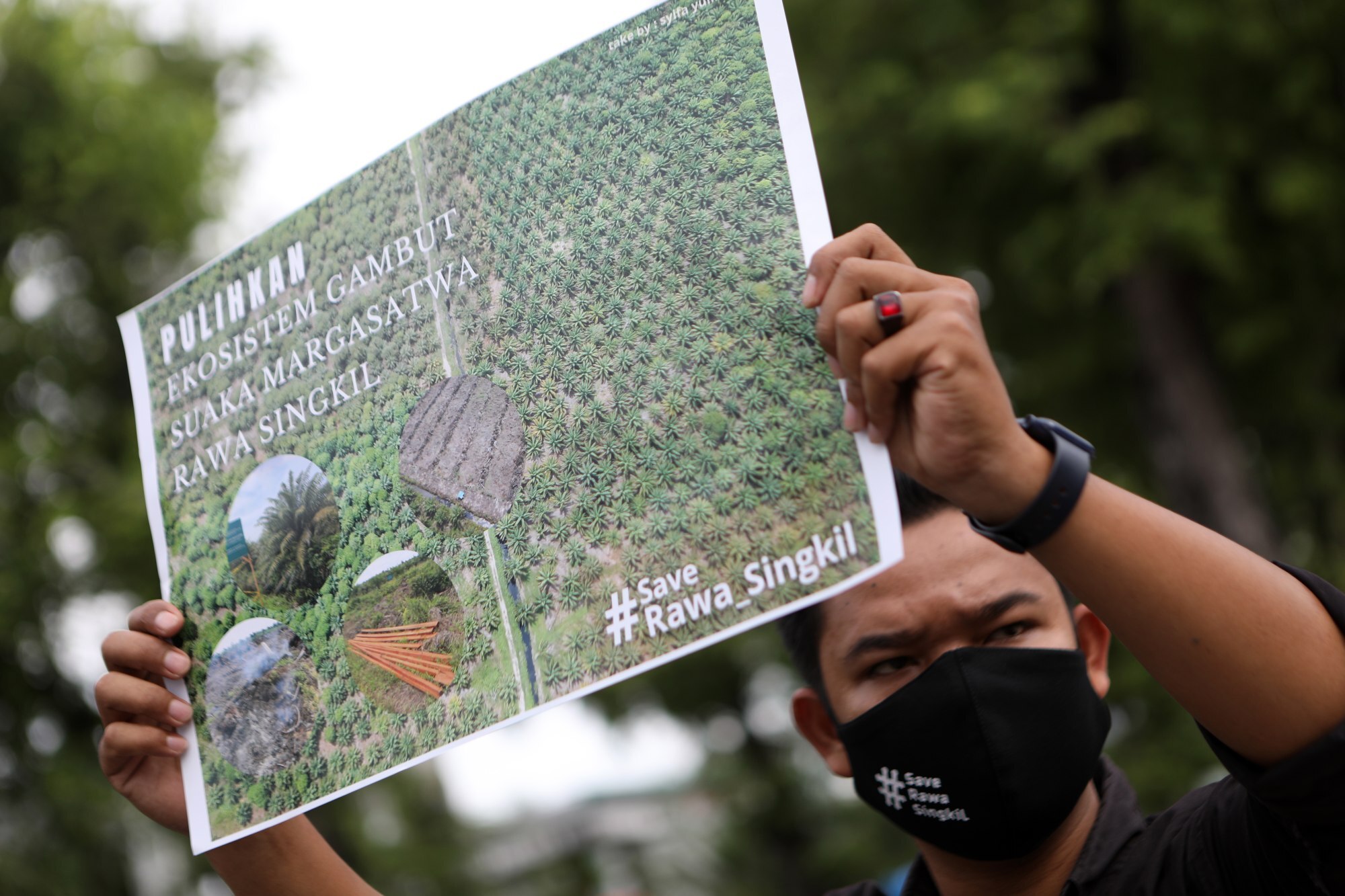

Some 3.1 million hectares of oil palm plantations – or 19 per cent of Indonesia’s total oil palm cover – were located inside in the country’s forest estate as of the end of 2019, despite a law banning the practice, according to a recent report by environmental groups Greenpeace and TheTreeMap. The forest estate covers national parks, wildlife sanctuaries, and Unesco sites across Sumatra, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, and Papua. According to the groups, which described oil palm plantations as “the largest single cause of deforestation in Indonesia over the past two decades”, more than 332,000 hectares of land previously mapped as orangutan and Sumatran tiger habitats have been planted with oil palm.

Expanding palm oil plantations jeopardises Indonesia’s climate aims: report

In the report, Greenpeace identified eight Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil member companies with more than 10,000 hectares of illegal plantations each, including one Singapore-based palm oil company and two Malaysia-based companies.

According to a study launched in May by Forests and Finance, a coalition of research groups and civil organisations, Chinese financial institutions also provided around US$15 billion in loans and underwriting services between January 2016 and April 2020 for companies that are driving tropical rainforest deforestation by producing commodities such as palm oil, pulp and paper, beef, soy, rubber, and timber in Southeast Asia, Brazil, and Central and West Africa.

“There are three sides that are responsible for this, the government, the companies, and the investors. Investors should be aware because they can assess the companies’ environmental, social and governance indices. This could be damaging to their reputation,” says Iqbal Damanik, forest campaigner at Greenpeace Indonesia.

“We are also calling for financial institutions such as banks to no longer fund companies that destroy the environment, including deforestation. They need to be more aware so that their sustainability claim is real.”

In September, Indonesia ended a deal with Norway that had promised a US$1 billion grant if Jakarta could cut carbon emissions from deforestation, under the UN’s Reducing Emissions caused by Deforestation and Forest Degradation scheme. Indonesia’s Foreign Ministry said it was terminating the agreement because Norway was delaying on a payment of US$56 million to Jakarta for preventing the release of 11.2 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent from 2016 to 2017. In a statement, the Norwegian government said that the discussions for the payment had been “progressing well” until Jakarta ended the deal.

“Since it is Indonesia who cancelled the deal, we are questioning the government’s commitment to stop deforestation. It provides a clue that Indonesia is not confident that it could curb its deforestation rate in the next few years,” said Mufti Fathul Barri, director of Forest Watch Indonesia.

Indonesia expects deforestation to claim up to 14.6 million hectares by 2050 or 6.8 million hectares with policy interventions, as laid out in the country’s long-term strategy for low carbon and climate resilience.

A numbers game

Instead of zero deforestation, Indonesia has opted to rehabilitate forests and peatland in a bid to absorb the same amount of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere that is released by deforestation, a strategy dubbed forestry and land use net carbon sink.

But many researchers say that so-called carbon offsetting does not actually reduce emissions in the long run. Deforestation and peatland degradation contributes about 60 per cent of Indonesia’s total carbon emissions.

“We are far from hopeful [that Indonesia can cut its carbon emissions from deforestation]. If the government’s approach is to rely on a carbon net sink strategy, it is very possible that they would play up the numbers, while improvement does not happen on the ground,” Mufti said.

“The carbon [emissions] released from deforestation are bigger than the amount of carbon absorbed by forest rehabilitation. If we cut trees in a 100,000-hectare forest area, we should rehabilitate 200,000 hectares of forest.”

Mufti also questioned Widodo’s claim during his speech at COP26 that 3 million hectares of forest had been rehabilitated between 2010-2019, as data published by the environment and forestry ministry said only 1 million hectares had been rehabilitated from 2011-2020.

At the conference, Widodo said that the annual deforestation rate in 2020 of 115,500 hectares was the lowest in 20 years, a statement repeated by Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi during a joint news conference with her UK counterpart Liz Truss on Thursday. However, Greenpeace Indonesia said 4.8 million hectares has been deforested from 2011-2019, compared to 2.45 million hectares from 2003-2011.

Young vs old

The country’s youth climate activists have also voiced their disappointment at Indonesia’s apparent lack of action to tackle the climate crisis.

Devirisal said that he started becoming environmentally aware in 2017, after learning about the climate crisis from his friends in environmental groups. That year, he set up an informal, self-funded, environment-focused school for the Aru Islands’s children, who can “pay” for the education with plastic waste. Every month, Devirisal gives as much as 70 per cent of the money he earns – as a clean water and sanitation worker and consultant for the local disaster agency – to the school.

Indonesia’s clean energy dream: a victim of coronavirus, or politics?

Devirisal is calling for the government to stop deforestation and start the transition to renewable energy, “if Indonesia is really committed to stopping the impacts of climate change”.

If no concrete action is taken soon, Iqbal from Greenpeace Indonesia predicts that Jakarta’s economic drives will clash with the demand of younger generations for a greener future.

“Young Indonesians are aware that their future will depend on the environment, if the environment collapses, there will be no economic growth,” he said.

“So in the future, the demand from Indonesian youth will be very, very loud if the government hesitates to quit the dirty economy.”