Japan’s birth rate takes a nosedive amid rising costs of having a family

- The country expects about 880,000 births this year, a decrease of around 200,000 from just a decade ago

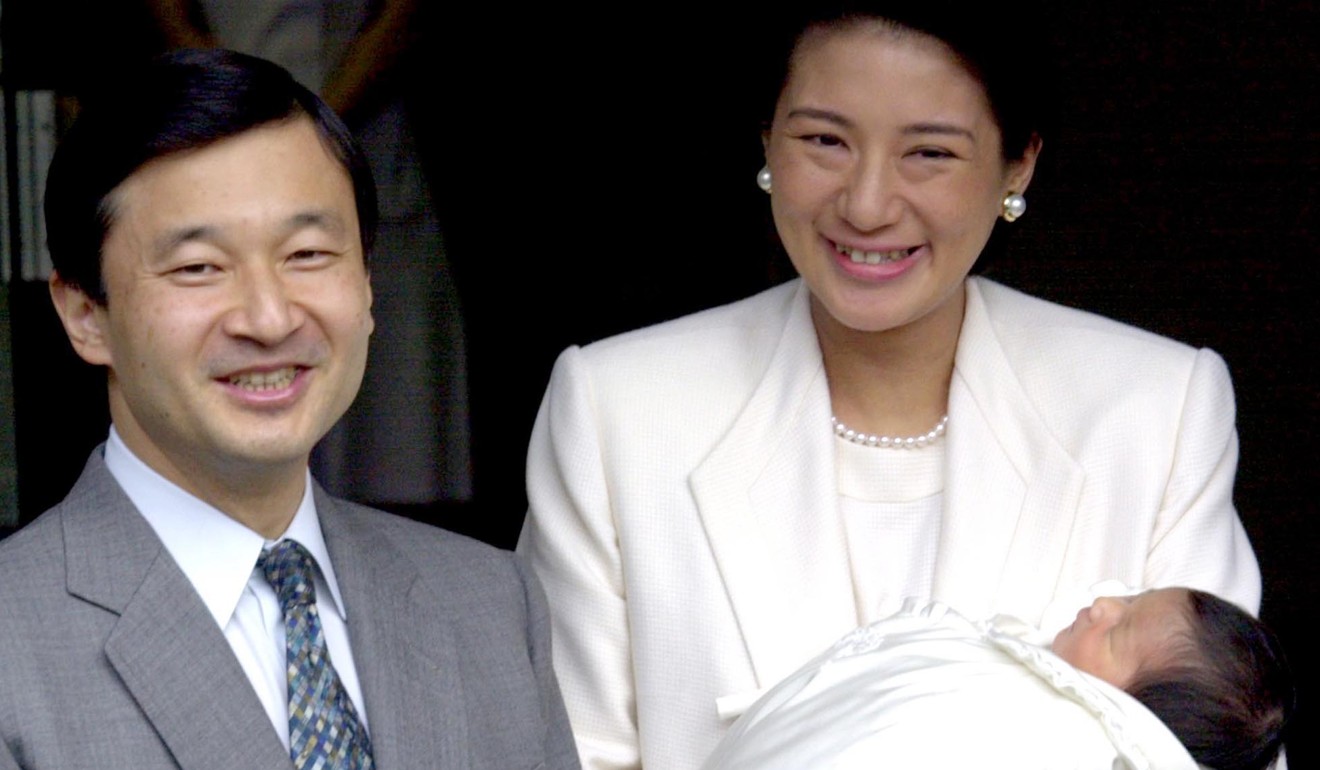

- Theories for why the birth rate has plummeted include one that is hard to prove – a desire for children to be born in the new Reiwa era after Emperor Naruhito’s coronation

This year, however, there are some unique factors to take into account, said Hiroshi Yoshida, an expert on the economics of ageing at Tohoku University.

Japan scraps stand-up comic’s end-of-life ad campaign amid backlash

“The birth rate has been gradually increasing for the last couple of years but I believe this can be attributed to the people who previously put off marriage finally going ahead and marrying and starting a family,” he said.

“And that means that now, we are likely to see the birth rate return to a gradual downtrend.”

Another consideration is that the nation’s “echo baby boomers” – those born amid the surge in births between 1971 and 1974 – are all reaching their mid-40s, meaning there are fewer women of child-bearing age.

“There is certainly that kind of psychological effect to take into account and we saw the same thing happening 20 years ago, when many people wanted to wait and have their children in the new millennium,” Yoshida said.

If that assumption is correct, then the evidence should become apparent in the next few months, he added.

Japan expects to see about 880,000 births this year, a decrease of around 200,000 from just a decade ago and the lowest figure since records were first accurately collated in 1899. In the late 1940s, some 2.7 million children were born in the country every year.

The nation’s fertility rate, or the number of children that a woman gives birth to on average, also declined this year, falling for the third consecutive year to 1.42. The level that is needed to maintain the population at the current level stands at 2.07.

As Japanese population shrinks, Chinese, Koreans arrive in growing numbers

For most couples, the biggest hurdle to them having children is often money.

“We live in the countryside in Nagano so it’s not a problem for us but all of my friends in the city say they want to go back to work after having children, but they can’t because there are not enough places at crèches or kindergartens,” said Emiko Livesey, 36, who lives in the town of Nozawa Onsen with her British husband and two sons, aged 4 and 5 months.

“But money is definitely a concern for us,” she said. “We have talked about having another child – my husband would really like a daughter – but we have to take into consideration the cost of education a few years in the future.”

Livesey and other parents say that although the government has introduced initiatives designed to ease the burden on couples who want to have children, such as making all crèches free, costs are still too high for many people.

“People stop after having one child because they just can’t afford to have another one,” she said. “But if they were to receive help on the financial side of things, I’m sure that they would have more.

“Sadly, it all boils down to money.”