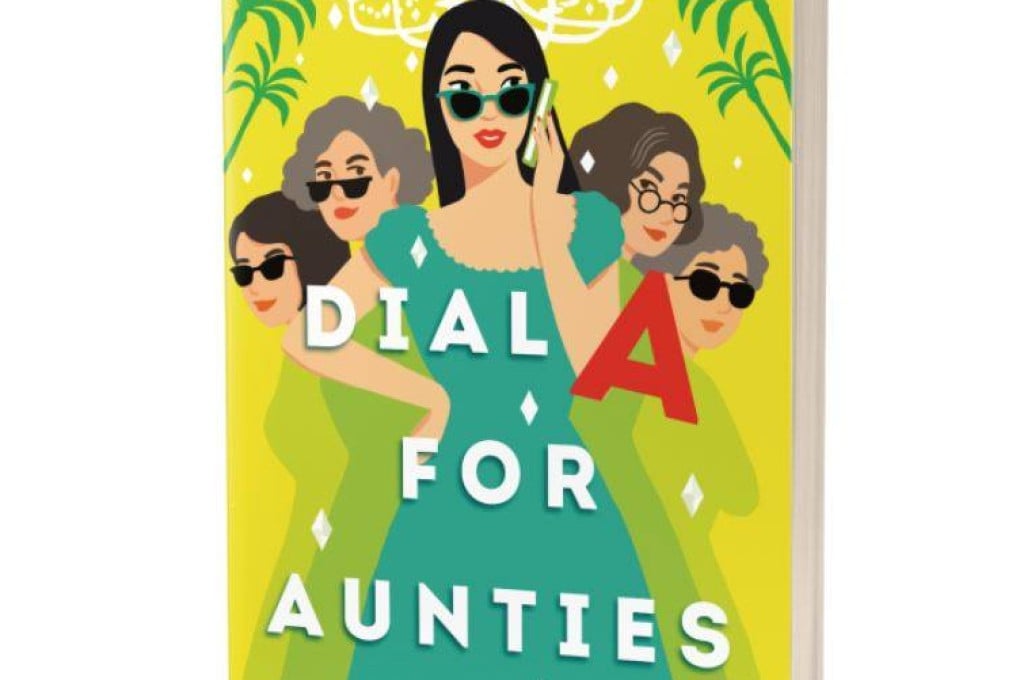

Lunar New Year: how Asian aunties went from asking about your love life to a Netflix movie

- Indonesian-Chinese writer Jesse Sutanto has sold the rights to her book Dial A for Aunties about a California wedding planner who accidentally kills her blind date

- Sutanto, who learned the true power of ‘aunties’ as a young person in Singapore, says they give the lie to Western stereotypes of ‘quiet and submissive’ Asian women

Among the many characters at those reunions, there is likely to be one that stands out for her inquisitive nature, sharp powers of observation and – quite possibly – her thoughts about your love life and all that weight you’ve been gaining recently: the “auntie”.

Unlike Western “aunts”, Asian “aunties” need not be blood relatives; people use the term loosely to refer to women who are a decade or two older and are afforded some form of seniority in the family’s social circle.

Aunties are famed for probing younger generations about their love lives. Singles can expect a grilling about why they don’t have a partner yet and whether they will ever get married; newlyweds can expect questions about when they are having children; parents will brace themselves for questions about their weight.

Indonesian-Chinese writer Jesse Sutanto knows this all too well, having grown up with what she describes as a reliable, if nosy, network of aunties in her life.