As Indonesia’s Chinese revive original family surnames, others get inspiration from Javanese customs, American culture and Islam

- Name-giving in Indonesia has a colourful history for most of its 1,300 ethnic groups; for the Chinese, it was troubling when they had to abandon their names

- Today, Western and Islamic influences play a part in naming babies, but even the pandemic and K-pop have provided inspiration

For a minority ethnic group like the Indonesian Chinese, who make up less than two per cent of Indonesia’s population, its history of name-giving has been both colourful and contentious. Although Chinese people settled in the Indonesian archipelago as far back as the 16th century, the majority arrived as economic migrants in the early 20th century.

How Indonesian-Chinese food in the ‘flavour lab’ of Jakarta survived Covid

But naturalisation did not stop Indonesian Chinese from experiencing the stigma of being seen as foreign. In 1967, in an attempt at “assimilation”, the Indonesian government issued a decree compelling all Indonesians of Chinese ancestry to abandon their Chinese names in favour of Indonesian ones. It was followed by a ban on the public use of Mandarin and expression of Chinese culture.

For Surabaya-born Hwely Ongkowijoyo, 44, the 1967 regulation led his grandparents to convert his family name, Wang or Ong in Hokkien, to Ongkowijoyo. The new Indonesian-ised family name remained in use for two generations until 2013, when Ongkowijoyo decided to revive the original family name by legally naming his newborn daughter Vivian Wang.

“For two generations, our family had used the name Ongkowijoyo and we felt that change was needed to move with the times. Ongkowijoyo sounded like [it was] from another era,” Linda Trisnawati, 45, Ongkowijoyo’s wife, said.

Trisnawati said that for her generation and that of her parents, the use of Chinese names had been out of the question.

“No Indonesian court or government agency would have allowed us to use our Chinese names. We would have been accused of not being patriots.”

The lifting of the ban in 2000 under President Abdurrahman Wahid heralded a new era for many Indonesian Chinese, although most remained cautious.

“When my son Alexander was born in 2004, we still registered him as an Ongkowijoyo. We knew that the ban was no longer in place but we wanted to wait and see if it held up. In 2013, we eventually plucked up the courage to revert to Wang,” Trisnawati explained.

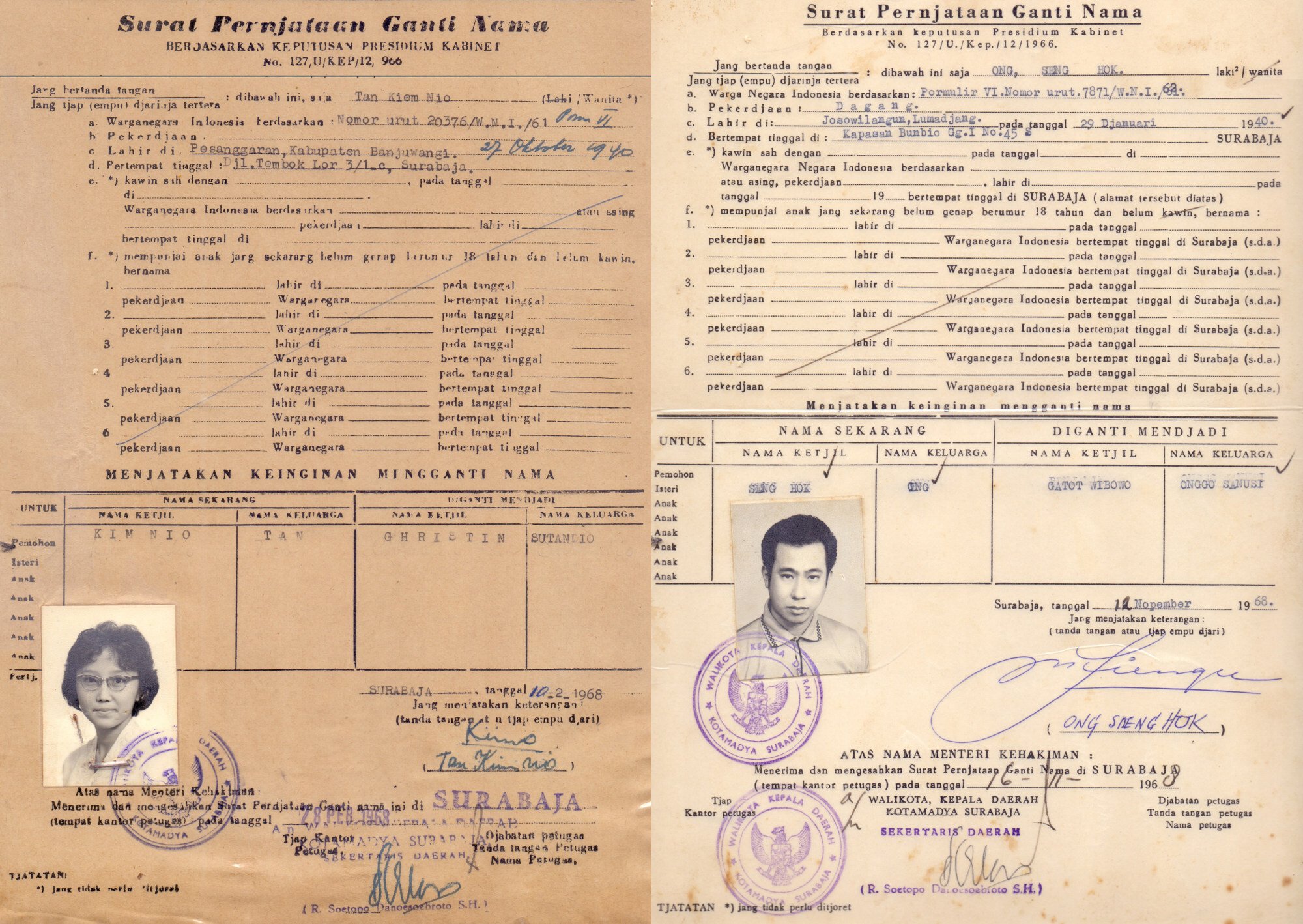

This writer’s family had a similar experience. His late mother, who legally went by the name of Christin Sutandio, had initially chosen “Grace” to replace her Chinese name, Kim Nio, in 1968.

But government officials vetoed the name Grace because it was too foreign-sounding. In the end, she had to settle for Christin, minus the “e” as the English spelling was also deemed too foreign. Sutandio had been agreed upon by her family as the Indonesian-ised version of the surname “Tan” or “Chen”.

This writer’s father also went through the same process, becoming an Indonesian citizen in 1962 and changing his name from Ong Seng Hok to Gatot Wibowo Onggosanusi. Being an avid reader of Javanese “wayang” legends, which had derived from Vedic sagas, he chose the name “Gatot” after a character from Mahabharata, Gathotkacha (Gatotkaca in Javanese), son of the Pandava Bhimasena.

Afterwards, at a tournament, the name Guntur had to be called repeatedly before King entered the arena because he had himself forgotten his new name. Oddly enough, his old name had become such a household name in Indonesia that the press continued to refer to him as Liem Swie King instead of Guntur.

Why Chinese Indonesians and their children are learning Mandarin

Both the first and second presidents of Indonesia, Sukarno and Suharto, had no last name. Another practice from this era which is rarely prevalent today is for parents to change the name of their offspring as they get older.

Old Javanese customs prescribed a change of name for sickly children because it was believed that the original name was ill-suited, hence the resulting ill-health.

The day a court ruled my Chinese dad was a ‘bona fide’ Indonesian

During Indonesia’s Dutch colonial period between the 17th and 20th century, new names derived from both Dutch and Malay were adopted eagerly by the populace due to their novelty value. In the 1920s, for example, many children were named “Kantoor”, which means “office” in the Dutch language. Indonesian natives who had converted to Christianity such as those in Manado and East Nusa Tenggara also preferred Dutch Christian names.

Historian Adrian Vickers, author of A History of Modern Indonesia, told This Week In Asia that new words in the Malay language, which was used as the lingua franca instead of Dutch, became names as well.

He gave the example of how Balinese in the 19th century started using new words and terms associated with events and celebrities as children’s names.

“In the early 20th century, the King of Klungkung called his two children Cokorda Karcis (Ticket) and Cokorda Beras (Rice) after the royal household had been exposed to these Malay words for the first time.”

Why do Indonesians use English to talk about the Chinese?

Exposure to American culture from the 1970s onwards saw many Javanese adopt surnames for the first time. American-ised nicknames also became popular, such as in the case of Indonesian tycoon widely known as Bob Sadino, whose real name was Bambang Mustari Sadino or the late Ali Alatas, foreign minister for 11 years, who was popularly called Alex.

Novelty value in names could also be inspired by religion in Indonesia. As a stronger Islamic identity began to manifest itself among Indonesian Muslims during the 1990s, more opted for Arabic names and their variants to give their children.

“In the past, parents would ask the local cleric to name their children. But with growing literacy and internet technology, parents have been able to consult diverse sources of inspiration for new names.”

Fighting prejudice against Indonesia’s Chinese … with a museum

But unique foreign names can be tricky, especially those which do not roll off the tongue for most Indonesians. A common English name like Matthew is usually pronounced as “Mati-U” by most Indonesians, with Mati meaning “dead” in Indonesian. If a name is indeed a prayer, then this one may be something prudent parents will want to avoid.