Back To The Future | Opinion: Why a kick in the teeth is good for Chinese kung fu

When mixed martial arts fighter Xu Xiaodong beat ‘thunder master’ Wei Lei in a Sichuan duel it was not tai chi he was thrashing – but its corrupted form

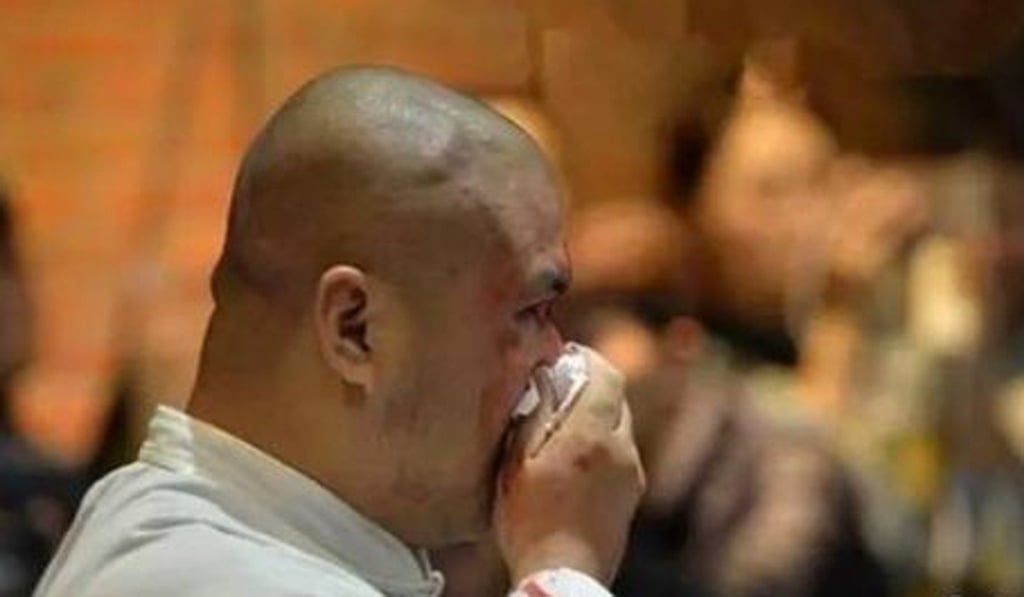

Sometimes a kick in the teeth is the best thing in the world for you. Let’s hope this will be the case for Chinese martial arts. This week, a viral video of how a mixed martial arts (MMA) boxer thrashed a tai chi master in a fist fight in Sichuan (四川) shocked the public, but it should come as no surprise to professional fighters.

World Cannabis Day: ‘Flying leaves’ defy stigma to soar to new heights

Not Xu. He accused Wei of fraud and questioned tai chi as a fighting technique. The two got into a heated spat over cyberspace that eventually led to their duel in Chengdu (成都), Sichuan, on April 27.

Wei’s humiliating defeat sparked debate in China over the truth of one of its most treasured traditions. For millions who grew up reading books, watching films and listening to stories of glorious kung fu, it is hard to stomach that such legends may be just tall tales. Like football to Brazilians, kung fu has become a quintessential part of Chinese identity. In no culture other than Japan have ancient fighting techniques been elevated to such status.

WATCH: Viral video of tai chi master’s defeat by MMA fighter sparks kung fu debate

This has not always been the case. In fact, while Chinese have practised martial arts for millennia, the public’s obsession with them is a modern phenomenon. Wuxia (martial arts) is the oldest genre of Chinese film and remains hugely popular today. Its rise in popularity goes hand in hand with the spread of nationalism. Kung fu has become an expression of Chinese resistance to foreign humiliation, a symbol of cultural uniqueness.