The questions facing Chinese investment in Bandar Malaysia

There is more to the saga of Kuala Lumpur’s troubled new business district and transport hub than mere monetary investment

The Bandar Malaysia project was launched in May 2011; a 197ha development under the real estate arm of Malaysian state fund 1MDB that was meant to be a new business district of Kuala Lumpur as well as a major transport node, housing the terminus of the High Speed Rail to Singapore and perhaps Bangkok.

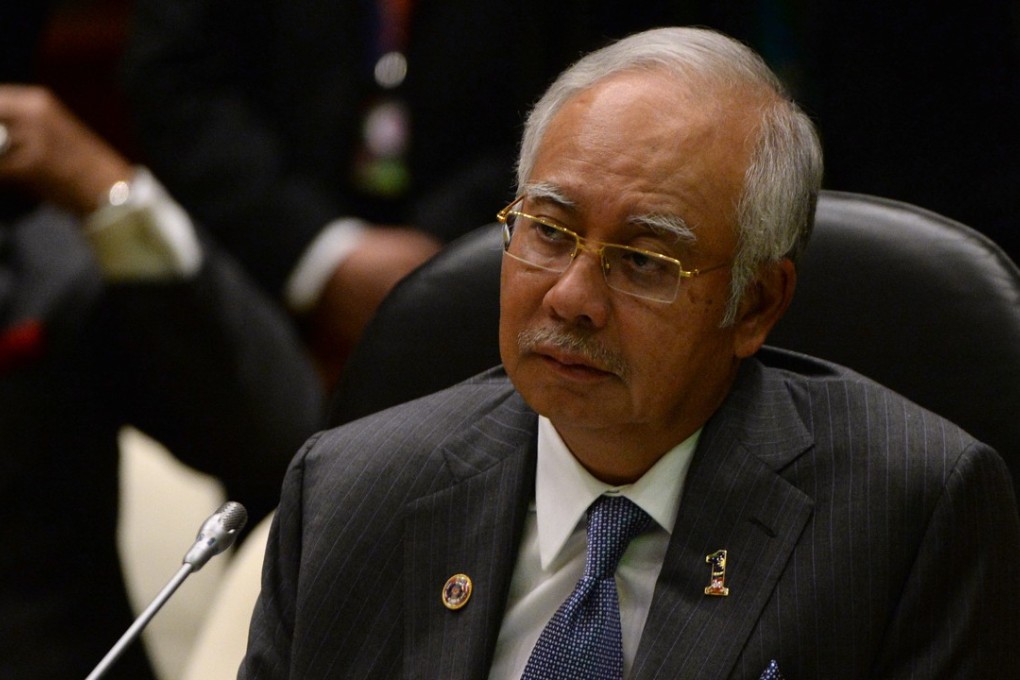

After the fallout from a scandal at 1MDB, where funds had allegedly been misappropriated, Bandar Malaysia fell under the auspices of TRX City, a wholly-owned subsidy of Malaysia’s Ministry of Finance.

In December 2015, 60 per cent of Bandar Malaysia was sold to a consortium comprising Iskandar Waterfront City and the China Rail Engineering Corporation (CREC), a Chinese state-owned company, at a signed value of 12.35 billion ringgit (HK$22 billion). This consortium thus became the master developer for Bandar Malaysia. The projected market value of that agreement today, based on the illustrated selling price of 2000 ringgit psf, is 42 billion ringgit.

The hidden costs of China’s lifeline in the 1MDB scandal

On May 3, 2017, the contract was terminated by the ministry on the grounds that the consortium had not fulfilled its payment obligations and that it was unable to prove that it had the 1.93 billion ringgit required to move the Sungai Besi airbase.

It was also reported that CREC had not attained the necessary Chinese regulatory approvals. While the consortium disputed these claims, the media added to the confusion by reporting that Arul Kanda, the former Chairman of the Board of Bandar Malaysia and director at TRX City had been removed due to a conflict of interest.