Opinion: Ignore Silk Road hubris, China will grow old before it gets rich

President Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road plan is rooted in the past: here are five lessons from history that suggest assumptions of China’s inevitable rise are mistaken

A rising China has turned us all – especially in Southeast Asia – into amateur historians.

President Xi Jinping’s signature initiative to revive the ancient Silk Road trading routes is rooted in the past, therefore the pageantry, rhetoric and indeed the substance of last week’s high-profile “Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation” in Beijing cannot be understood if one ignores history.

Living as they do in China’s “armpit”, Southeast Asians have no choice but to learn a lot more about the Middle Kingdom.

Why China should be wary of overconfidence

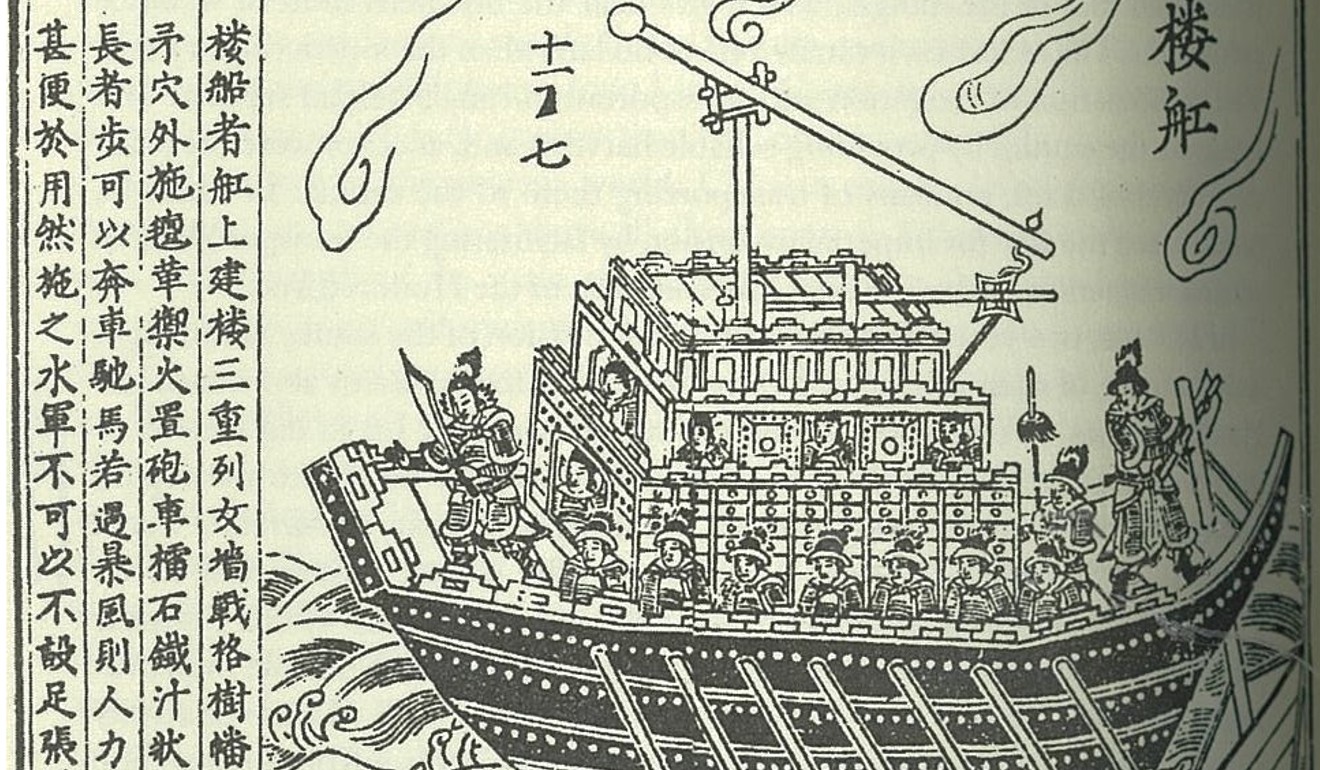

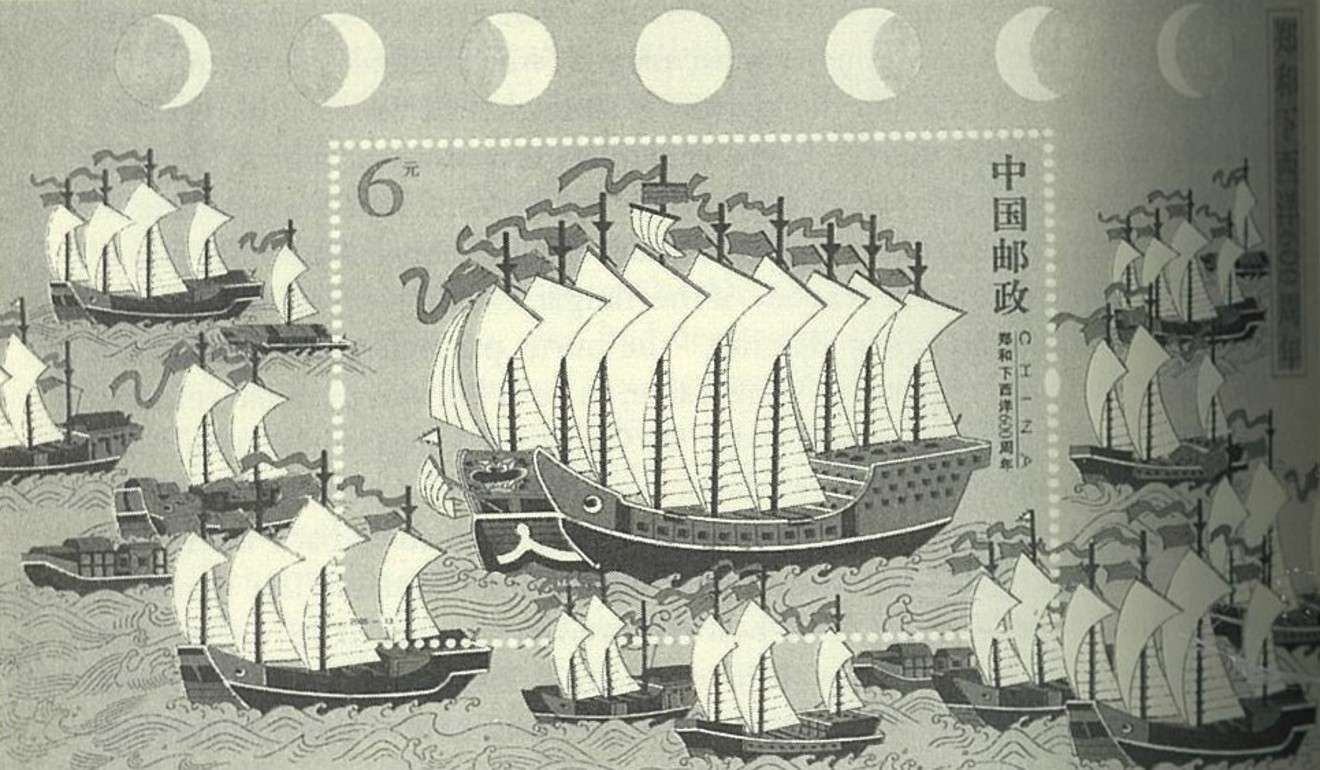

Given the strong maritime focus of the Belt and Road initiative – Beijing’s plan to link Eurasia through land and sea links and infrastructure into a China-centred trading network – it’s also critical to understand China’s chequered oceanic forays – stretching from the dynamism of the Han, Tang and Ming dynasties to the disastrous xenophobia of the Manchu Qing.

In this respect, Lincoln Payne’s 744-page tome The Sea and Civilization: a Maritime History of the World provides a superb overview of how the great civilizations faced sea-borne challenges.

Tracing the ups and downs of China’s maritime engagement, the reader comes away with five key points.

First: there has been no discernible consistency in China’s relations with Southeast Asia. Over the centuries, it has veered from great interest to isolationism, sometimes within a space of a few years.

Witness the speed with which the great Ming armadas under Admiral Zheng He (1405-1433) were abruptly followed by stringent prohibitions on foreign trade.

What this means is that Southeast Asia cannot depend on China’s long-term interest in the region.

This leads to a second point: history has proven that China’s leaders are easily distracted when its internal stability is threatened. Given its size, the resources needed to manage such challenges have been a huge and constant drain on the exchequer.

The vulnerability of China’s northern and western borders (as well as threats of peasant revolts), have necessitated a degree of constant military preparedness, sapping even further precious resources.

Consequently, internal policing has always been a fact of life – something that remains the same even in the Xi Jinping era today.

Third, the strategic importance of China’s rivers – which have long been an essential part of internal connectivity as well as domestic security and trade – feed its inwardness.

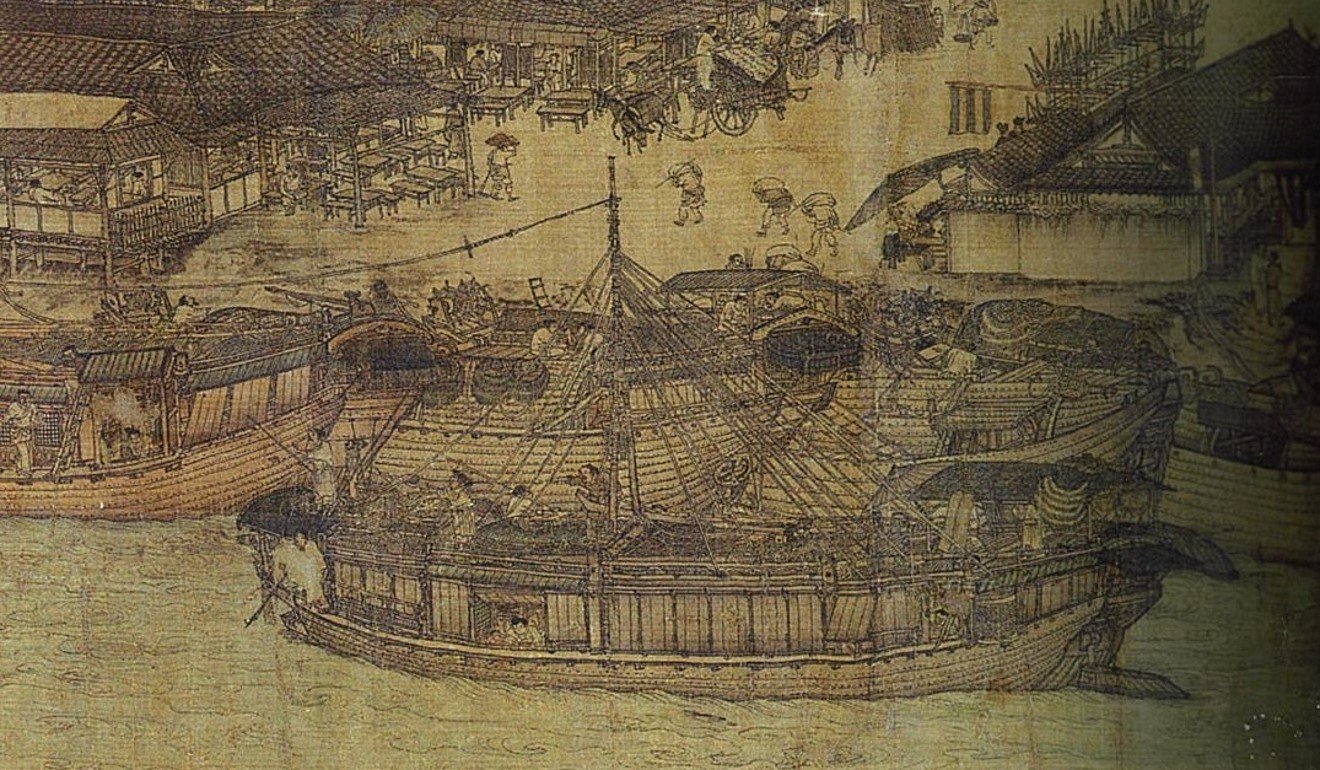

Over the centuries, the great rivers – the Yangtze, Pearl and Yellow – have been developed to enhance irrigation, prevent flooding and ease transportation. A web of canals and domestic waterways have been built, thereby uniting the country; with the most famous of these – the Grand Canal – linking the rich agrarian South to the parched North around Beijing.

A lesser-known example but perhaps even more extraordinary is the 36.4km Lingqu Canal which was built with immense loss of life during the Qin Dynasty from 219–214 BC.

This strategic waterway connected the Yangtze and Pearl River basins, providing a means of travelling by ship from Chang’an (the Imperial capital at that time) to Guangzhou – a distance of more than 2,000km.

WATCH: Belt and Road - what, when, why and how?

It’s important to remember that the emphasis on river-going craft negated to a large extent the need to develop a strong sea-going shipping industry and this stymied trade with the Southern Seas for many centuries.

Fourth, in the era before the steam engine, shipping had to follow the all-important monsoon winds. In the winter, when land is colder than water, the Northeast Monsoons would blow from China and Japan southwards, reversing in the summer, as the land warmed, creating areas of higher pressure and bringing torrential rains from the South.

As such, the monsoons determined the sailing schedule and imposed a particular time frame on trading routes between China and Southeast Asia.

The monsoons across the Indian Ocean weren’t in any way synchronized, meaning that travellers hoping to reach the wealthy Malabar coast and or beyond were forced to wait in Southeast Asian ports for the winds to shift, thereby slowing down pan-Asian trade routes.

This in turn led to the steady build-up across Southeast Asia of Chinese traders who would remain for a few months before returning to the ports of Guangzhou and Quanzhou.

It’s important to note that the Chinese never sought to occupy and monopolise the ports they visited. They traded, sojourned and then they departed: this is in marked contrast to the Portuguese, the Dutch and British who sought to use their firepower to dominate trade.

Indeed, the Hokkien people were to be major beneficiaries in the 11th and 12th centuries with the formation of the zealously pro-trade Southern Song Dynasty based in what is now Hangzhou.

Honing their navigational skills and trading skills, they grew to dominate Asian trade travelling as far as East Africa and the Gulf of Persia.

Finally, indigenous Chinese thinkers – most notably Confucius – have been stringently opposed to commerce.

In the Analects, Confucius states dismissively: “The gentleman is conversant with righteousness, the small man is conversant with profit.”

As such, when Confucian scholars and mandarins held sway as they did for much of the Ming dynasty – controlling access to the Emperor – trade and diplomacy always suffered.

It’s also worth noting that Buddhism (an alien and largely sea-borne faith) also constituted a major challenge to Confucian orthodoxy and dominance. The tension between Buddhism and Confucianism may well have been an added reason for the distrust and at times, active suppression of the South Sea trade.

In the 9th and 10th centuries, trade between China and India boomed as religious scholars and monks moved backwards and forwards between the great seat of Buddhist learning, Nalanda on the Ganges and China, providing an enormous boost to Southeast Asia, especially the Sumatran trading entrepot of Srivijaya as religious texts and sacred artefacts were shipped to China.

Who learned the lessons of Thai baht crisis: China or Europe?

Nonetheless, Confucian mandarins were extremely vocal in their criticism of the importation of tropical luxuries – sandalwood, cloves, tortoise shells and rhinoceros horn – seeing them as frivolous.

Typically, Chinese-made silks and ceramics were insufficient to pay for the imports and copper coinage was exported in large amounts to pay for the purchases, contributing in turn to inflation, the scourge of the country’s economic life.

As such, it would be mistaken to assume that China will inevitably become a global, even regional hegemon.

Current awe of China’s mounting power is directly linked to the incompetence of US President Donald Trump’s administration.

Xi is the apogee of a calm, dignified global leader, all-too aware of the scale of his responsibilities. Trump, by contrast, is nothing more than a pumped-up reality TV star.

Separately, although China’s infrastructural achievements – the toll-ways, railways, ports and cities – are dazzling, these are a mere snapshot in time.

North Korea is addicted to missiles: it’s intervention or war

The underlying reality is of a fundamentally indebted, extremely unequal and vastly over-built society that is going to be knocked sideways by its own demographic earthquake – as decades of the one child policy come home to roost – and China’s population growth starts to falter.

The best advocate for this astonishing but entirely plausible argument is the former New York Times Shanghai bureau chief, Howard French, whose book Everything Under the Heavens: How The Past Helps Shape China’s Push for Global Power is a masterful explication of its barely hidden demographic woes.

French’s core point is that China has squandered its demographic dividend. Birth rates (projected to stand at 1.51 per cent in 2020) have fallen below replacement levels and median age rates (forty-nine years old by 2050) are climbing quickly.

Why China has just 15 years to secure its place in the world

All this means that China will grow old before it grows rich and that the resources needed to care for its elderly alone (it is projected to have 329 million people over the age of 65 by 2050, equal to today’s combined populations of France, Germany, Japan and Britain) will sap its capacity to project internationally.

So while the Belt and Road conference may have made China seem like a rising giant, let’s not lose sight of the fact that it has feet of clay.