As Beijing urges understanding of Hong Kong’s Basic Law, it should look to its own backyard

The disappearance of five booksellers and aggressive investment by mainland Chinese companies have raised concerns for Hongkongers regarding ‘one country, two systems’

“The well water does not interfere with the river water”. The metaphor is one of the most memorable when it comes to describing the relationship between Hong Kong and the Chinese mainland, and Beijing’s policy of “one country, two systems”.

Former president Jiang Zemin ( 江澤民 ) first popularised it in the wake of the Tiananmen Square crackdown in 1989 when he said Beijing would not impose socialism on Hong Kong while the latter should not meddle in mainland politics. At that time, Beijing was more concerned about Hong Kong being used as a base for subverting the Chinese government.

How things have changed. As Hong Kong gears up to mark the 20th anniversary of the city’s return to China next month (following its commemoration of the 27th anniversary of the Basic Law earlier this year) the metaphor seems to have been turned on its head.

WATCH: One country, two systems survives, says Hong Kong Legco President Jasper Tsang

Over the past 20 years, the city and the mainland may have forged closer economic and financial links, and people to people exchanges, but their minds seem to have drifted further apart over the future of Hong Kong and its political relationship with the mainland.

At stake is the Basic Law, which has served as the city’s constitution to safeguard rights and freedoms since the 1997 handover. Citing the Basic Law, the pro-democracy camp has bitterly complained that Hong Kong’s rights, freedoms, and high degree of autonomy are under threat, saying the city has been short-changed over a promise to introduce universal suffrage. Meanwhile, Beijing has countered that misunderstanding and deliberate misinterpretation of the law – as evidenced by calls for self-determination or Hong Kong’s independence – meaning it has to take a tighter grip on the city, leading to a vicious cycle.

Nationalism cuts both ways for China’s global ambitions

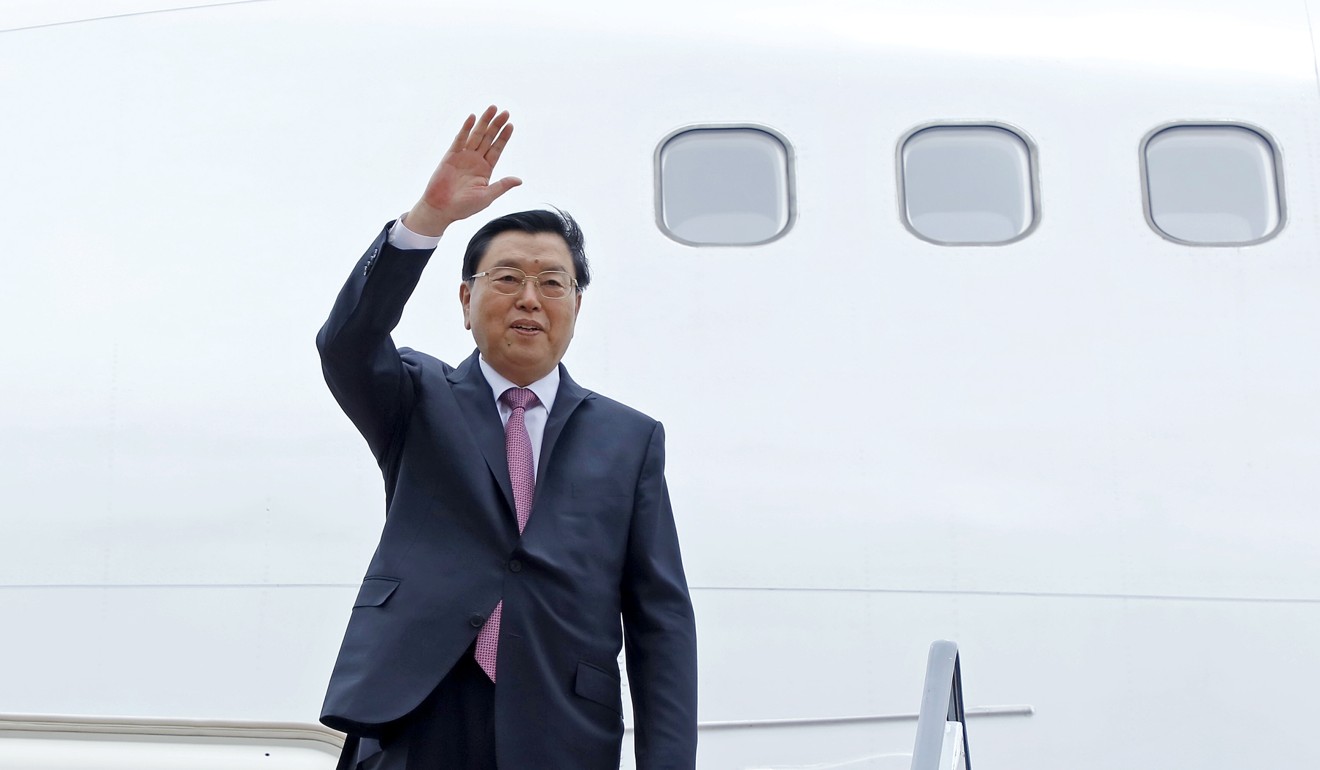

Last week, Zhang Dejiang ( 張德江 ), China’s third most senior leader, warned Hong Kong not to confront the central government over its “high degree of autonomy” and said it must enact its own national security laws to ensure national sovereignty over the city.

Zhang, speaking at a forum marking the 20th anniversary in Beijing, made clear Beijing had the final say in granting a degree of autonomy to Hong Kong rather than sharing power with it.

In April, Wang Zhenmin, the legal chief of the central government’s liaison office in Hong Kong, warned the policy of “one country, two systems” could be scrapped if it became a tool to confront Beijing, reiterating that “one country” must come before “two systems”.

As the political tension forms the backdrop to the 20th anniversary of Hong Kong’s return to China, it is necessary to understand Beijing’s reasons behind what it thinks has gone wrong with what was once billed as one of the world’s great political experiments, barely 20 years into its 50-year design.

Looking back, the Chinese leadership now believes the implementation of “one country, two systems” went off balance from the start.

Why China should be wary of overconfidence

Back in the first few years of the HKSAR, both the central government and Hong Kong were very keen to make sure the formula would work well by placing emphasis on the two systems, with the overly optimistic view that it would set an example to Taiwan. Hong Kong has refused to reinstate the special branch tasked with national security and intelligence and Beijing placed strict restrictions on central government departments and local authorities from bothering Hong Kong in any unnecessary way.

The year 2003 proved to be a watershed as the Hong Kong government was forced to back down from enacting contentious Article 23 legislation obligated by the Basic Law, which outlaws treason, sedition and other national threats. The legislation has been on hold since half a million people took to the streets to protest in 2003.

Since then, Beijing has started to put the stress on “one country” by using its powers of interpreting the Basic Law to lay down the rules which are binding on local courts. After five interpretations and the street protests that culminated in the Occupy movement that paralysed parts of the city in 2014, Beijing is now seeking tighter control of the city. It is particularly worried about the nascent movement of a smattering of youth seeking self-determination or independence for the city.

But as the Chinese leadership urges Hongkongers to seek comprehensive and precise implementation of the Basic Law and the principle of “one country, two systems”, they should also take a serious look at how the mainland side fares in this regard.

Indeed it is good to hear that Zhang said in his speech that the central government departments and the mainland’s local authorities should also take the lead in studying the Basic Law, abiding by the law and raising awareness of the law, along with the Hong Kong government.

As Beijing tries to assert national sovereignty over Hong Kong, there have been palpable signs of failure to adhere to the principle of “one country, two systems”.

One notable example is the disappearance of five Hong Kong booksellers in late 2015 and the concerns this saga raised about the city’s autonomy and potential loss of freedoms.

Forget leading the world, China must get its own house in order

Secondly, China’s governance over Hong Kong also has plenty of room for improvement. At first glance, the central leading group on Hong Kong and Macau affairs, now headed by Zhang, a Politburo Standing Committee member, is supposed to be Beijing’s highest authority to oversee and co-ordinate all matters related to the two cities, mainly through the Hong Kong Macau Affairs Office in Beijing and the liaison office in Hong Kong. But because a dozen other central government bodies have stakes in Hong Kong and Macau affairs, coordination of those departments has proved less effective.

One key issue is over how to regulate investments by the mainland businesses in Hong Kong. While there is no dispute that mainland investments have helped boost Hong Kong’s economy and its status as one of the world’s premier financial centres, some deals have proved less helpful and their intentions questionable.

The latest example is the land buying spree by the mainland conglomerate HNA group, which owns Hainan Airlines, among other assets. In November, it raised more than a few eyebrows in Hong Kong by splashing out HK$8.8 billion for a site on the old Kai Tak airport, doubling the former highest price paid for land in the same area. In just over four months, the group spent HK$27.2 billion to acquire four lots with a combined land size of nearly 400,000 square feet. The price paid for each of these acquisitions was well above the market expectations.

Is Xi’s new ‘core’ status a sign of strength, or weakness?

Such aggressive investments have fuelled Hong Kong’s already red hot property market, in which soaring prices have been a key source of social discontent and resentment among the city’s youth.

Some may argue those investments are business decisions but the bigger question is: are they good for the future of Hong Kong? ■

Wang Xiangwei is the former editor-in-chief of the South China Morning Post. He is now based in Beijing as editorial adviser to the paper