Don’t hold your breath for Xi to reform China’s economy

It is likely the Chinese president believes he has struck the right balance: one in which market forces have some leeway, but the state still holds the levers of control

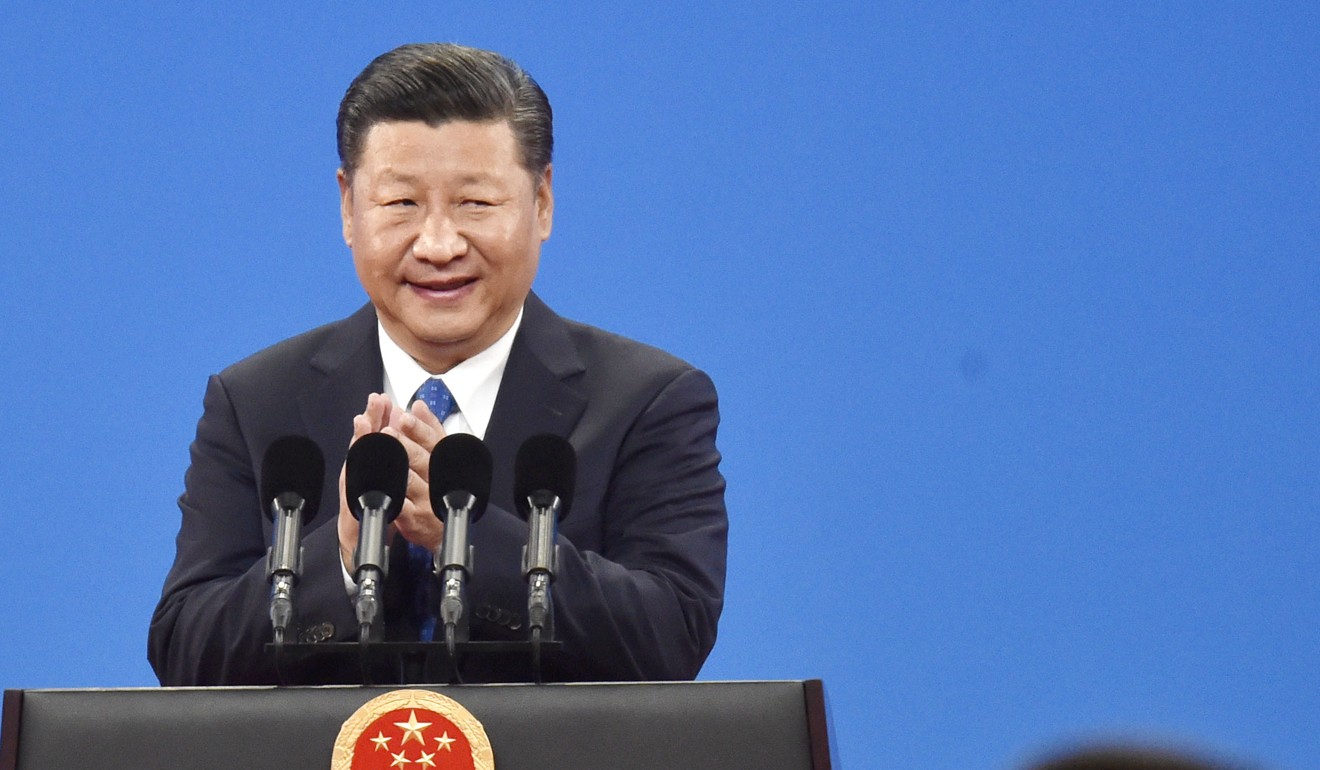

When Xi Jinping stands up on Wednesday to deliver his “work report” to the Communist Party’s five-yearly congress, foreign businesspeople – and many in China – will be listening closely for indications the Chinese president is preparing to accelerate the process of economic liberalisation. They are likely to be disappointed.

The hope is that Xi – now he has successfully consolidated his grip on the party, cleaned out corrupt cadres and surrounded himself with like-minded allies – will turn in his second five year term as president towards economic affairs.

Move over Aussies, the Chinese are coming to Indonesia

Now that Xi no longer faces stiff opposition from senior officials intent on protecting their own economic interests, optimists hope he will roll out a suite of market-oriented reforms – the sort that has long been urged by the International Monetary Fund. These would include steps to open up state dominated sectors to private business, privatise many of the smaller state-owned firms and overhaul the governance of the larger ones, and allow more foreign competition especially in China’s closely protected service sectors.

Naturally, many businesspeople and investors would welcome a reform programme that levels the playing field between the state and private sectors, and between domestic and foreign players.

But they are not the only ones. Many economists and policy advisers argue that greater liberalisation is essential to foster the competition and business innovation China needs to sustain economic growth, avoid the dreaded “middle income trap” that has ensnared other developing countries, and achieve Xi’s objective of creating “a moderately wealthy society” within the span of his presidency.

Retired Macau triad boss back in circulation with cryptocurrency

But although Xi is likely to talk glowingly of “supply-side reform” in language lifted straight from the economic era of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, his sense of the term differs greatly from that of Western free market enthusiasts back in the 1980s.

Far from implying a hands-off approach to production, the president’s notion of supply-side reform involves imposing output quotas to eliminate excess industrial capacity and manage prices.

Similarly, under Xi, state enterprise governance reform has not seen Beijing take a step back and set up investment firms to hold the government shares – similar to Singapore’s Temasek. Instead it resulted in a number of government directed mergers that turned big state companies into even bigger ones, more tightly under Beijing’s control.

And privatisation – dubbed “mixed ownership reform” – has done little or nothing to reduce the state’s stake in China’s economy. The sale earlier this year of 62 billion yuan (HK$73 billion) of shares in the listed subsidiary of telecoms giant China Unicom is a case in point. It was billed as a privatisation deal that would see the state’s 63 per cent shareholding cut almost in half, with private sector investors including Tencent and Alibaba brought in to revitalise the business. In reality, however, many of the “private” investors were really joint ventures controlled by state concerns.

When the dust settled, it turned out that Beijing’s stake in the privatised company had barely been reduced – to 58 per cent.

What’s more, far from allowing enterprise to flourish free from state control, Beijing is actually tightening its grip over private business. According to reports published last week, China’s Cyberspace Administration is planning to acquire direct shareholdings in some of the country’s biggest internet companies, potentially taking a formal role in their management.

All of this suggests observers should not hold their breath for continued economic liberalisation. It looks very much like Xi has taken free-market reforms just about as far as he wants them to go.

After the efforts of the last few years, the prices of most Chinese goods and services – from coal to housing to bank loans and even the exchange rate of the yuan – are set largely by market forces. However, Beijing has retained its commanding influence over key sectors of the economy, and the government still has the ability to step in and manipulate prices if officials feel they are straying too far from desired levels.

In short, China has adopted a mixed economic model, under which market incentives direct much of the day-to-day activity, but where state control ensures that that activity supports the government’s greater political goals. And as far as Xi is concerned, it seems to be working. Growth remains remarkably rapid for such a large economy, and most importantly, it is relatively stable. Administrative measures have largely managed to contain bubbles in China’s local property markets. State companies have been pushed to deleverage. And officials are increasingly confident that the regulatory crackdown initiated earlier this year will succeed in reining in China’s runaway credit growth without triggering a financial crisis.

Guess what Chinese travellers are bringing back home? VPNs, lots of them

In other words, it is likely Xi believes he has now structured the economy he wants: one in which market forces are given enough leeway to generate moderately rapid growth, but in which the state still holds all the levers of economic – and therefore political – control. If so, further liberalisation would appear not just unnecessary, but dangerously destabilising. Under Xi, economic reform has reached the end of its road. ■

Tom Holland is a former SCMP staffer who has been writing about Asian affairs for more than 20 years