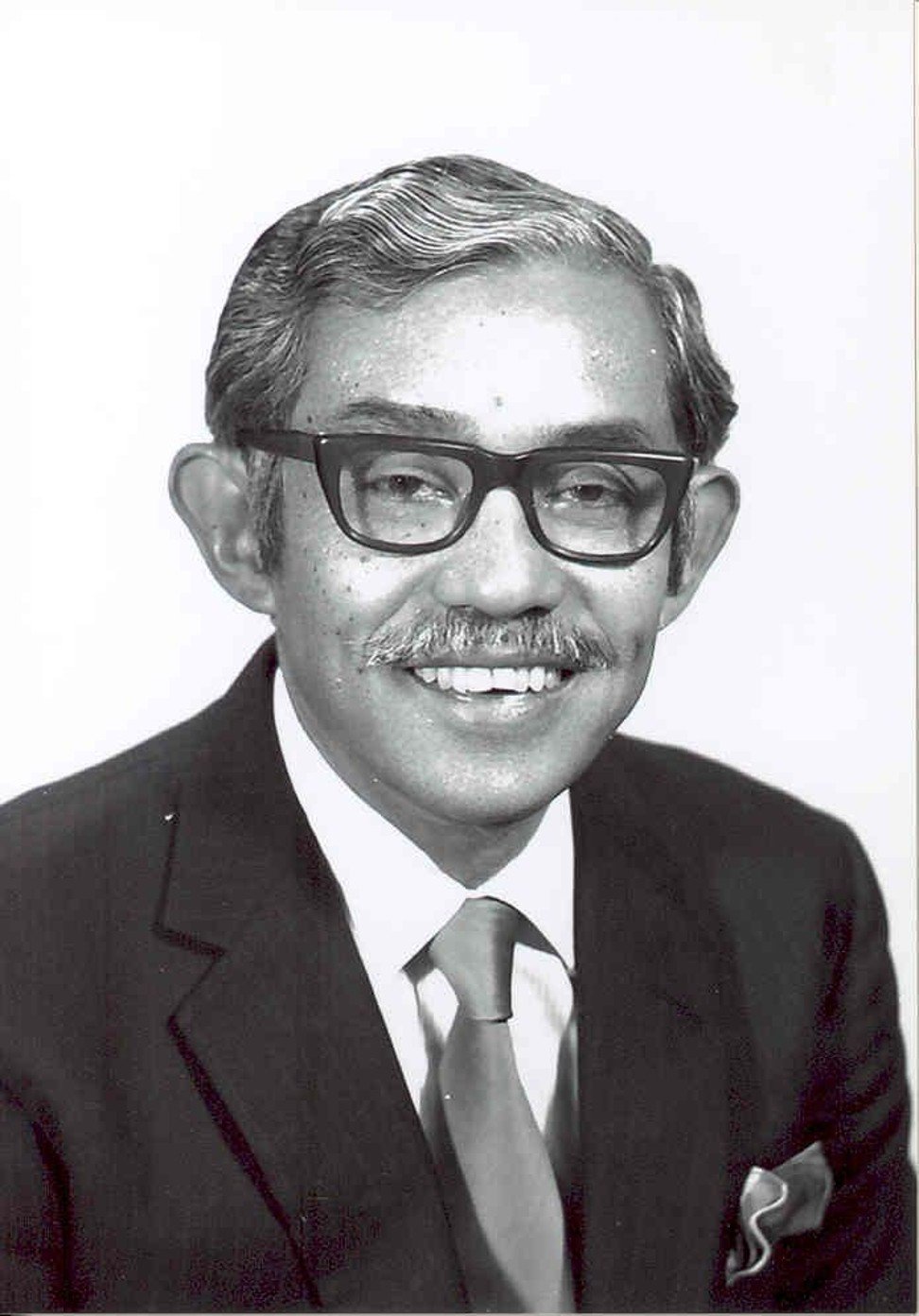

Exclusive | How I launched Malaysia’s national shipping line (and what Genghis Khan had to do with it): the Robert Kuok memoirs

In the fifth extract from Robert Kuok’s memoir, the Malaysian-born tycoon reveals how patriotism drove him to launch the country’s national shipping line and how he drew inspiration from the Mongol warrior

CUT THE APRON STRINGS AND CAST OFF

In 1967, word reached my ears that the Blue Funnel Group was coming to set up the national shipping line of Malaysia. Blue Funnel was probably the largest shipping conglomerate in Britain at that time. It owned Blue Funnel, Glen Line, Straits Steamship Co in Singapore, and many other lines. The Executive Chairman, a man whom I recall walked with a bad limp, was making frequent lobbying trips from London to Kuala Lumpur. I was interested in applying for the licence, so I chatted with a few of my Malay civil-servant friends. They agreed that I should put in a similar application to be considered for the right to establish the national shipping line.

My interest was partly patriotism … to help Malaysia not be tied to the apron string of the ex-colonial government

My interest was partly patriotism – a desire to help Malaysia to launch its own independent shipping line and not be tied to the apron strings of the ex-colonial government of Britain through Blue Funnel. I had become interested in shipping from about 1964, due to our large-scale buying of sugar for our refinery, wheat for our flourmill and our international commodities-trading activities. For example, we bought free-on-board sugar from India and delivered it to the Government of Indonesia on a cost-and-freight basis (sellers only wanted to sell on the basis of delivery at their own ports; buyers wanted the sugar delivered to their ports. Thus, covering the span of the ocean was my risk).

In those days, shipping was quite volatile and freight rates could sometimes shoot up 25-30 per cent. Since margins on sugar trading were small, you could easily make money on your trade, but lose on the freight. There was one problem: I knew nothing about shipping. I did know that in any business, unless you know the tricks of the trade, you can be badly burnt. I couldn’t even submit a decent memo for the application. So I looked for a partner.

A FRANK ADMISSION

On one trip to Hong Kong, I had been introduced by a Malay civil-servant friend to a man called Frank WK Tsao. I remembered that Tsao was a shipping man, Chairman of International Maritime Carriers, so I telephoned him. I said I would like to come and see him to discuss a business proposal. He gave me an appointment and I flew to Hong Kong. When I went to his office, Tsao was only mildly friendly. I was quite humble in my approach. I told him that we had met. He said, “Oh yes, we have met, we have met.” In business life, you learn early on that you must swallow your pride. I told him that some Malay civil servants, who wanted to stir up competition, were encouraging me to submit an application to set up a national shipping line.

There was one problem: I knew nothing about shipping. I did know that in any business, unless you know the tricks of the trade, you can be badly burnt

I said, “I can’t differentiate between the front and rear ends of a ship,” which was a bit of an exaggeration, “so why don’t you come and help me to set up the Malaysian national shipping line? You’re well known in the shipping business. Are you willing to become my partner?” Without thinking for a second, he retorted, “Do you know, so and so and so and so have also approached me. They are Tan Sris, and I turned them all down.”

He was virtually saying “And who are you? I’ve turned down people way ahead of you in the pecking order in Malaysia.” When I heard these remarks and saw his body language, I said, “I’m sorry then. I thought I would give you first crack. I am going to go at it.” I didn’t tell him what a determined man I am in life.

Malaysia-Singapore Airlines, Siamese twins set for separation: the Robert Kuok memoirs

I concluded, “Never mind, nothing has been lost by this little chat we’ve had. Thank you for receiving me.” I got up and was walking out when he shouted, “Oh, no, no. Please, Mr Kuok. Don’t go! Don’t go! Sit down, sit down.”

To this day I don’t know what made Frank change his mind. I had one shipping expert on staff, Tony Goh, a Singaporean- Chinese who was running my plywood factory. Tony had been a manager at Ben Line, a Scottish liner, before he joined me in 1964. So I sent Tony Goh to draft the memo with Frank Tsao.

I rewrote certain parts to suit the reading style of the Malaysian civil servants, and we submitted the memo in the joint names of Kuok Brothers and Frank’s International Maritime Carriers. A little later, I heard that we were one of the leading contenders. I asked Frank to meet me in Kuala Lumpur. I had made up my mind that we should pick one day to call on as many important ministers as possible. From eight in the morning we whipped around Kuala Lumpur at a furious pace, such as you can’t do today due to the traffic, and saw seven ministers by lunchtime. Some of them gave us good time and good hearings, and we told them the same story. In the afternoon, we visited one or two more.

I remember calling on the Prime Minister, the Deputy Prime Minister, Home Minister Tun Dr Ismail, Finance Minister Tan Siew Sin, Minister of Works Sambanthan and Minister of Transport Sardon Jubir.

OUR SHIP COMES IN

Within two or three weeks, we were picked at a cabinet meeting to start the national shipping line, Malaysian International Shipping Corporation (MISC). We were like a dark horse coming from behind in the last furlong and pipping the favourite at the post!

I was Chairman of the Board and provided business management guidance. Frank Tsao’s side provided the shipping expertise. Just around the time of MISC’s formation in 1968, my dear friend Tun Dr Ismail resigned from government when he found that he had cancer. I immediately invited him to be the first Chairman of MISC.

I was inspired by the example of Genghis Khan, who, when he conquered cities, usually turned the spoils over to his generals and soldiers

Frank Tsao already knew Tun Dr Ismail through a textile-mill investment Frank had made in Johor (Dr Ismail resigned from MISC after the May 13, 1969, riots to return to the Cabinet. I then took over the chairmanship until the 1980s). Our first two ships came from the Japanese. Simultaneous with our moves to start the shipping line, there was an initiative by the Malayan Chinese Association (MCA) to demand war reparations from Japan.

The Chinese community was angry about the Japanese massacre of innocent Chinese and was seeking compensation for this blood debt. Tunku Abdul Rahman, the Malaysian Prime Minister, supported the demand and raised the issue during official trips to Japan. The Japanese finally agreed to give two blood-debt ships to Malaysia, which the Japanese called “goodwill ships”. MISC started with these two cargo ships and paid for them on a monthly bare-boat, hire-charter basis. Frank’s ship architects and engineers in Hong Kong supervised the design and construction in Japan. Tunku Abdul Rahman made some very cogent suggestions about the design of the flag for this new national flag carrier.

MISC had an initial paid-up capital of 10 million ringgit. Since Kuok Brothers led the show, we took 20 per cent; Frank Tsao took 15 per cent. As the ships were reparation from the Japanese to the Malayan Chinese Association, not to the Malaysian nation, the vessels were assessed a reasonable value and the MCA was given MISC shares in lieu of payment.

MCA and other Chinese associations, combined, took 20-30 per cent, so in the beginning the holding of Kuok Brothers, Frank and the MCA group together was easily over 50 per cent. We had a fairly united board in the beginning. MISC started business in the second half of 1969 and quickly flourished. Much of the credit must go to Frank, the deputy chairman, who recommended capable managers such as Eddie Shih. Shih, another Shanghainese who had settled in Hong Kong, ran the show with Tony Goh. Very early on, Tony recommended his one-time colleague in Ben Line, Leslie Eu, who at the time was manager of Ben Line Bangkok. Leslie, the son of Burmese Chinese who had settled in Malaysia, quit Ben Line and came in as Managing Director of MISC.

YES, PRIME MINISTER

Within a year of our launching MISC, Tun Razak, who by then was prime minister, sent for me. Razak said, “I want you to make a fresh issue of 20 per cent of new shares. I’m under pressure because there is not a high enough Malay percentage of shareholding.” I said, “Tun, are you quite serious about this request?” He answered, “Yes, Robert.” So I replied that I would do it. I went back and, with a little bit of arm-twisting, persuaded the board to pass a resolution waiving the rights of existing shareholders to a rights issue (MISC was not yet a public company). Razak allocated all the new shares to government agencies. So, I was diluted to 20 upon 120 – the enlarged base – and Frank became 15 upon 120.

One or two years later, Razak again sent for me. He said, “I’m under a lot of pressure at Cabinet meetings. You know, Robert, it’s just the price of your success. MISC is doing well, people are getting envious. But now, instead of giving in to those factions, what I’ve decided is this: Issue another twenty per cent, five per cent to each of four port cities in Malaysia.”

I have always believed in some degree of socialism when you have made money

This entailed enlarging the capital base to 140 from the original 100, making the Malaysian Government the largest single shareholder and relegating Kuok Brothers to second position. And he again wanted the shares issued at par – the original issue price.

I said, “Tun, I have always cooperated with you, but it’s getting very difficult. Three, four years have elapsed from formation, but I would be loath to ask you for a premium since we are a growing company. So I will go back and ask the board again to issue shares at par to you. But Tun, can you please promise me that this is the last time?” He smiled and very gently signified his agreement, without saying the words.

Devils to friends, how China’s communists won over Malaysian PM Tunku: the Robert Kuok memoirs

GIVING LIKE GENGHIS

Then Frank and I decided that we should go public. Before we listed in 1987, I made quite a radical move, adopting a practice that I had used within Kuok Brothers. I explained to my Kuok Brothers senior directors that the MISC shares were now worth a lot of money, but only because of the great effort put in by other members of the board and many of the very deserving staff. I wanted to take about 15 per cent of our shareholding and sell the shares at par to deserving directors, staff and ship captains. Quite a number of people benefited from this move. I have always believed in some degree of socialism when you have made money. You know very well that you alone didn’t make it; it was a joint effort.

I was inspired by the example of Genghis Khan, who, when he conquered cities, usually turned the spoils over to his generals and soldiers. He was not selfish, and that is why he became the greatest general the world has ever seen.

Robert Kuok, A Memoir will be available in Hong Kong exclusively at Bookazine and in Singapore at all major bookshops from November 25. It will be released in Malaysia on Dec 1 and in Indonesia on Jan 1, 2018