Despite retirement, Xi’s right-hand man Wang Qishan is still within arm’s reach

At 69, China’s anti-graft tsar has stepped down from China’s Politburo Standing Committee, but his new special duties cement his continued political influence

Yet, due to the opaque nature of Chinese politics, there is more to this than meets the eye. Subsequent media reports lamenting the end of Wang’s remarkable political career could also be off the mark.

As reported by the South China Morning Post, he will still attend Politburo Standing Committee meetings where key decisions are made, a rare privilege that suggests his political influence will continue to be felt.

He is also expected to be named as the country’s vice-president at the next session of the National People’s Congress in March. Then, the national legislature will endorse the leadership line-up of the state, including re-electing Xi as the president for another five-year term and the senior officials for the Cabinet. But this will merely be a formality, as their government appointments were decided along with their party positions at the 19th congress.

‘Great Leader Xi’ or ‘Xi, the great leader’: it’s a fine line

Previously, there was some speculation about Wang’s role immediately following his retirement from the standing committee last month. This included whether he would take a leadership position in one or two of the party leading groups chaired by Xi himself, or perhaps help guide a newly formed commission which combines the anti-graft functions of the party and the government.

But Wang’s new roles, detailed by the Post, make more sense as such arrangements would enable the dynamic five-year working relationship between Xi and Wang to continue without breaching the existing informal rules on retirement and terms of services.

But at the age of 69, he was set to retire at the congress last month – informal succession rules mandate standing committee members step down at the age of 68. Long before the congress, many lobbied Xi to break the informal rules and let Wang stay on for another term. But in the end, Xi demurred, perhaps to avoid a backlash from other factions within the party.

Why a stronger Xi is being gentler in foreign affairs

While Xi is determined to keep him on, Wang’s new assignments have reflected political ingenuity and careful considerations that include taking precedents into account.

In the past, there were times when China’s vice-presidents were not Politburo members – Wang Zhen in the late 1980s and Rong Yiren in the 1990s.

And there is the precedent of Yang Shangkun, who was the state president in the late 1980s. Although he was a Politburo member, Yang was given the special privilege of attending the powerful Politburo Standing Committee meetings.

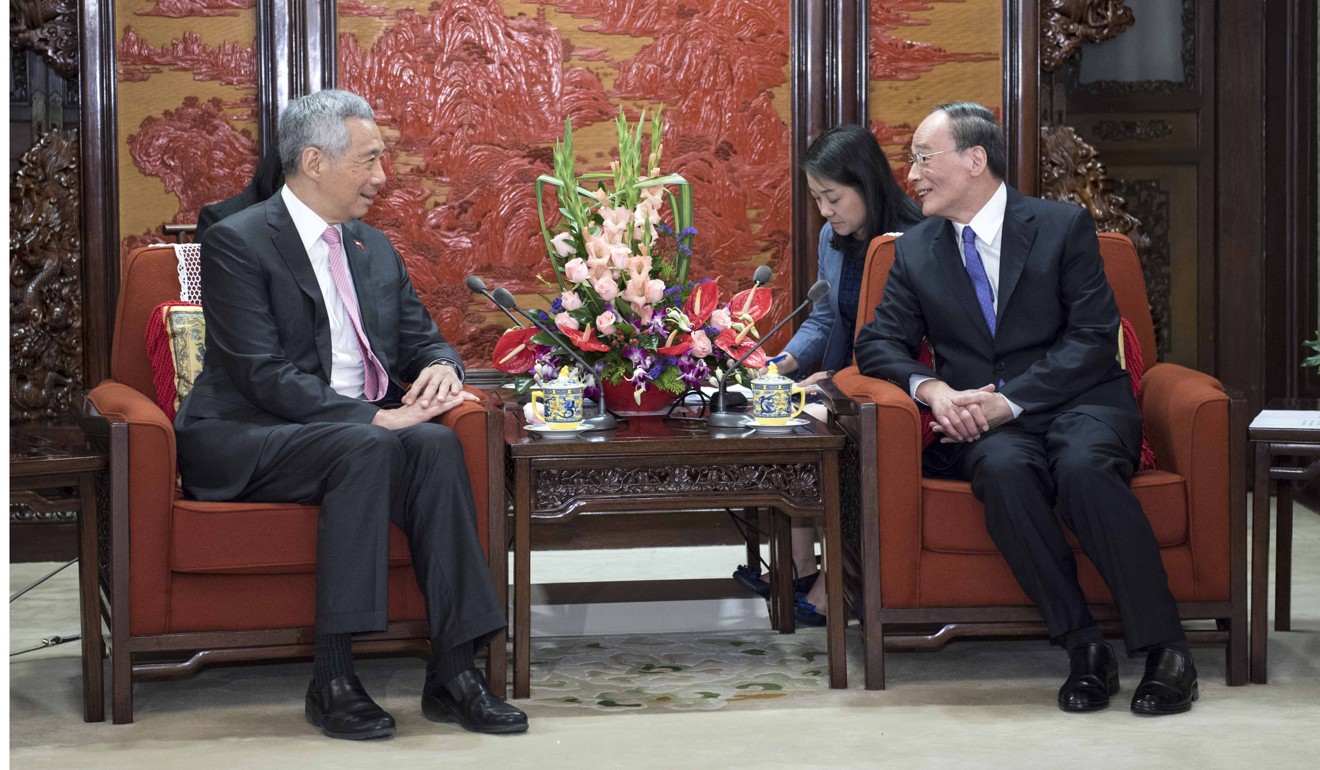

In his meeting with Lee, Wang pointedly told him that he had sought permission to hold their meeting, presumably from Xi. He should have done the same for his secret meeting with Bannon, which was later reported by overseas media.

What Xi’s new leadership team means for China’s economy

The new arrangements should suit Wang well. Although the vice-presidency is merely ceremonial, it will give him the public profile he needs to meet visiting heads of state.

His access to the Politburo Standing Committee meetings will give him a wider remit to be involved in more strategic issues than his previous portfolio, which focused on anti-corruption issues.

For Xi, Wang’s remarkable success in implementing his anti-corruption campaign and his proven skills as a great problem-solver and fixer are too valuable to allow him to just fade from the political scene. Furthermore, keeping Wang on will send powerful messages that the thrust of the anti-corruption campaign remains unchanged and this in turn will enhance the authority of the central government, Xi’s personal authority and China’s overall political stability. ■

Wang Xiangwei is the former editor-in-chief of the South China Morning Post. He is now based in Beijing as editorial adviser to the paper