Why Australia’s cure for Chinese influence is worse than the disease

Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull has cause to push back against undue political influence from Beijing, but the economic price, and the price paid by his fellow citizens who happen to be of Chinese descent, is too high

On a recent overnight flight from Beijing to Sydney, most of the passengers were mainland Chinese tourists looking forward to a respite of summer sunshine and fun, with some talking excitedly about the upcoming spectacular New Year’s Eve fireworks in Sydney, or hot-air ballooning over the Hunter Valley vineyards.

They seemed oblivious to a viral story trending on the mainland’s social media about Australia becoming the “most unfriendly” country to China during 2017, according to an online straw poll conducted by the Global Times, China’s most hawkish tabloid, sponsored by the People’s Daily.

But during my recent brief holidays in Australia, the unscientific poll results invariably came up in my interactions with Chinese Australians, and added spice to the dinner table conversation about how some of them had lived a surreal year of anxiety and angst.

Over the past year, Chinese Australians who form the largest overseas Chinese community in Oceania, have found themselves at the centre of unwanted attention and scrutiny from the Australian government, intelligence services and media. In what appeared a concerted campaign, some of the community’s prominent business leaders were accused of acting as possible agents of the Chinese government by seeking, at its behest, to influence Australia’s domestic politics through political donations.

Turnbull in a China shop: did Beijing bogeyman sway an Australian election?

The Chinese government was also accused of peddling its influence through the Confucius Institutes opening up across the country, mobilising Chinese students for political purposes, and pressuring Australian universities and publishers to suppress publications critical of China.

Many Chinese Australians have expressed genuine concerns that such a public outcry over the Chinese government’s political influence could trigger a serious anti-Chinese backlash against the whole community.

China is Australia’s largest trading partner and Australia is one of the most popular destinations for Chinese tourists, students and immigrants, as well as rich businessmen seeking investment opportunities.

Perhaps because of such close ties, the mainstream Australian media believed the Chinese government saw Australia as a target to expand its global influence.

On a broader scale, the Australian government and media are not alone in mounting a high-profile campaign against Chinese influence. The resistance against China is growing across the world for various reasons, and from an increasing number of Western countries – including the United States, New Zealand and Germany, as well as countries that have close ties with China, such as Pakistan.

Spies and a magic weapon: why are Australia, New Zealand so suspicious of China?

Compared to Western capitalism, China’s model advocates political controls by the totalitarian regime and the adoption of effective economic policies to continuously improve living standards in exchange for the mandate to rule.

For the moment, reactions from the Chinese government and its official media have been aggressive and indignant, accusing Australia and some other countries of harbouring a cold war mentality, lacking confidence and being jealous of China’s legitimate rise.

One official blog of the People’s Daily said in sarcasm that the resistance against China echoed a bygone era in which many Chinese called for boycotts of Coca-Cola, Hollywood and Western corporate systems during China’s early years of opening up to the outside world.

Frenzied Australian media fears foreign influence – ‘China’ foreign, not ‘US’ foreign

But all things considered, the resistance against China should be no surprise and is most likely to get worse in the coming years. History has proved that when a new power rises to assert its leadership role, it is bound to face resistance from the existing powers, based on fears of a zero-sum scenario in which the greatness of one country would diminish others.

Now cue China, which has sharp ideological and political differences with Western democracies. In particular, its opaque political system and lack of transparency over its intentions have understandably led to increased anxiety and countermeasures from many countries. But Australia’s intense campaign to curb the Chinese influence is overzealous and counterproductive for several reasons.

The heavy-handed efforts to root out the Chinese influence could lead to a witch hunt that hurts innocent, law-abiding Chinese Australians and Chinese students who are minding their own business, just like any other Australian.

Why Australia needs a smarter China policy

Secondly, the anti-Chinese policy could risk isolating the overall community of Australians of Chinese descent, which account for about 5 per cent of the country’s population. Traditionally, Chinese immigrants all over the world tend to keep to themselves and are reluctant to make their marks in mainstream society. A more toxic environment would make them even more wary, which would reflect badly on Australia’s proud multiculturalism.

In fact, some prominent Australian political leaders have already expressed dismay about the government’s de facto anti-Chinese policy and its adverse impact on the economy and its international standing.

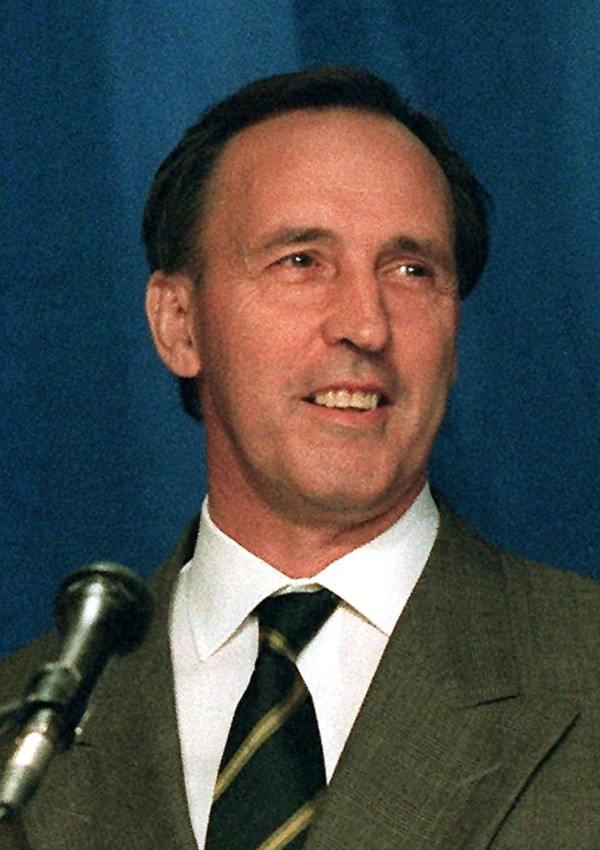

Paul Keating, a former prime minister, told The Australian newspaper that Turnbull’s government has failed to prioritise relations with Asia because of its anti-Chinese policy.

“The government doesn’t seem to understand the economic importance of the relationship with China or the strategic issues involved,” Keating was quoted as saying. “We are putting all of our faith in our relationship with China through the foreign policy lens of the US.”

A case in point, Australia has targeted a number of leading Chinese Australian businessmen who have made hundreds of millions of dollars in investments, creating new jobs and helping the economy.

Over the past year, two leading businessmen of Chinese descent have worn the unfortunate bull’s eye on their backs: Chau Chak Wing, an Australian citizen and Huang Xiangmo, an Australian permanent resident who applied for citizenship.

Both of them have been accused of donating millions of dollars to both sides of the political spectrum; even their donations to the Australian universities were painted as having an ulterior motive. The key argument against them and others appears to be the fact that they made their fortunes in China, and thus they must have close links with the Chinese government.

But the fast-changing political dynamics in China have led to the capital flight of tens of billions of dollars over the past few years as Xi has tightened the party’s controls over all sectors of the society and cracked down hard on cosy relationships between officials and businessmen.

In that sense, both Chau and Huang had the foresight to move their bases of operation to Australia long before Xi came to power in 2012.

Should Australia fear an influx of Chinese?

Both of them have denied any link with the Chinese government, and exhaustive media and government scrutiny over their business activities and political connections with Australian politicians left them untouched by the law, suggesting they have done everything by the book.

Other business leaders, such as Rupert Murdoch and Gina Reinhart, have successfully cultivated good relations with Australian politicians, in part by making generous donations. Unfortunately, when Chau and Huang tried to follow suit, their Chinese background made many suspect their allegiance.

In the case of Huang, the Chinese-language reports in Australia suggested he is the holder of a Hong Kong SAR passport and his wife and his children are all Australian citizens. And with reported investments worth more than A$800 million, Huang’s family-owned company is more Australian than Chinese. ■

Wang Xiangwei is the former editor-in-chief of the South China Morning Post. He is now based in Beijing as editorial adviser to the paper