Opinion | What India can learn from Asean in dealing with China

The summit between two nations that together represent 40 per cent of the world’s population could be an important step towards reducing tensions along the ‘spine of Asia’

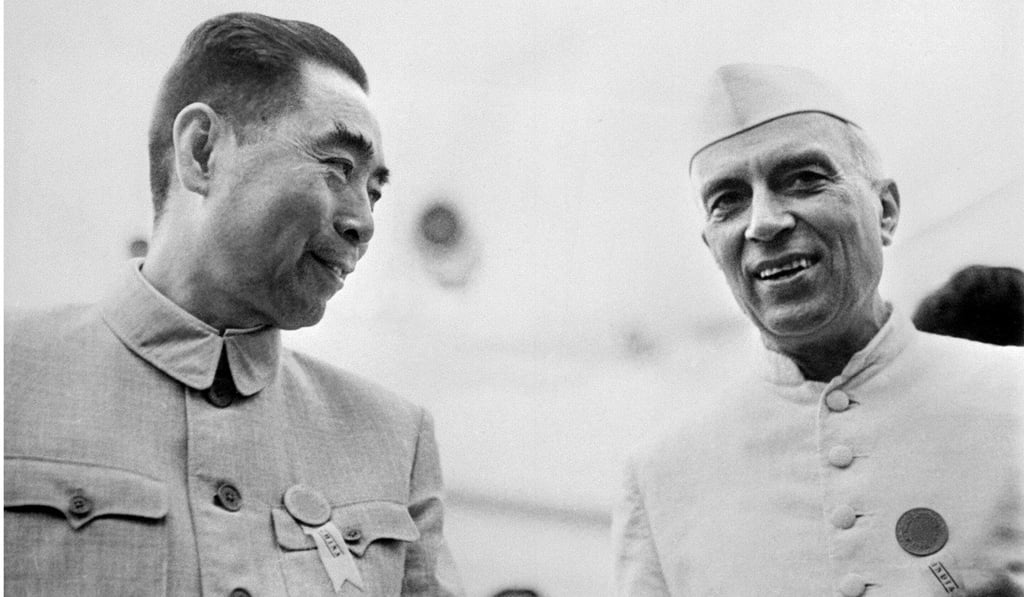

“Never forget that the basic challenge in Southeast Asia is between India and China. That challenge runs along the spine of Asia,” said Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister. Often charged with having soft-pedalled the threat to India from China, he was not oblivious to the competitive, often contradictory impulses that have driven India and China in their encounters with each other in modern times.

Media in both countries have been hyperbolic in their reactions to the Wuhan summit. Words like “reset” and “reboot” have been used to describe the process – both hardly fit. The historical burden and legacies from the past cannot be erased. The outstanding problems that complicate the relationship between the two countries, as well as their competitive coexistence in Asia and the Indo-Pacific, will not go away because of one handshake in Hubei.

Will Xi-Modi summit lead to deals on Belt and Road, investments, and border?

Even as the two countries speak of strategic partnership, coming to terms with the unhappy past in their relationship is a must if they are to learn from history. Even if they are not enemies (as the relationship between India and Pakistan is often described), there are adversarial characteristics to their ties. The Canadian writer, Michael Ignatieff once described the difference between enemies and adversaries by saying that “an adversary is someone you want to defeat. An enemy is someone you have to destroy”. With adversaries, “compromise is honourable. Today’s adversary could be tomorrow’s ally. With enemies, on the other hand, compromise is appeasement.”