Advertisement

Opinion | Mandela’s legacy lives strong in Asia, but can we say the same for its leaders?

From Myanmar to India and the Philippines, autocratic regimes have been on the rise since the South African leader and icon of inclusive democracy left his presidency

Reading Time:3 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

This month’s centenary celebrations in South Africa, marking the birth of Nelson Mandela, sadly remind us of the death of any other public figure whose unquestionable moral standing similarly eschewed bitterness and division, and promoted unity, democracy and peace through reconciliation.

That void extends to Asia, where Mandela was a beloved icon and an inspiration to a generation of human rights activists. And a current lack of similar leaders of stature is very much a testament to the unique position he holds in our collective consciousness.

But it also reflects how in the 20 years since Mandela left his presidency, autocrats are now in the ascendancy – as obdurate and as ruthless as ever. Meanwhile, the kind of inclusive democracy Mandela promoted is now hobbled and on the back foot.

Advertisement

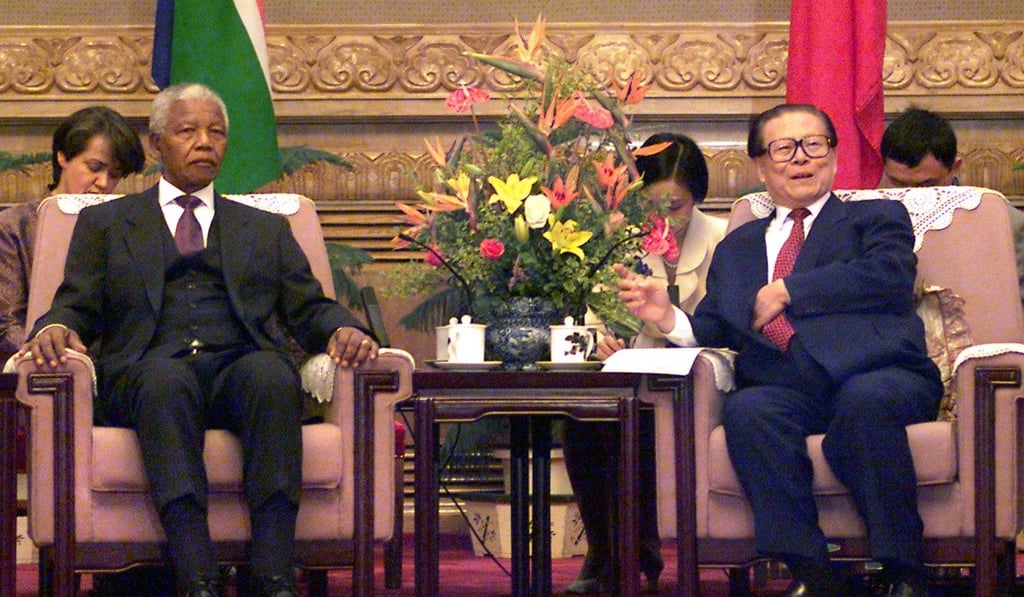

Autocratic regimes today are less likely to allow future Mandelas to walk free from prison or return from exile. China’s Liu Xiaobo, like Mandela, a Nobel Peace Prize winner, was only granted medical release from prison days before he died from liver cancer. China’s other Nobel Peace Prize laureate, the Dalai Lama, is 83 and likely will never be allowed back to his Tibetan homeland in his lifetime. Oddly, while many of China’s jailed dissidents say Mandela’s 27 years in prison inspired them and gave them strength, Beijing’s communist leadership also laud Mandela as an “old friend of China”.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x