Abacus | Turkey’s crisis shows a deeper disease – and Asia is infected too

The asphyxiating lira is a canary in a coal mine full of developing countries at the mercy of a strengthening dollar. Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and India should all hold their breath

As Turkey’s lira crisis has deepened over the last few weeks, businesspeople and investors around Asia have asked themselves whether Turkey’s troubles could spread by contagion and infect the region.

For the most part the answer they come up with is that what is going on in Turkey is “idiosyncratic” – caused by a set of conditions unique to that country. The chance that they will spread to Asia is small.

Unfortunately, they are asking the wrong question. They should not be wondering whether Turkey could be the cause of economic trouble in the wider world. Instead they should be asking whether the lira crisis is the result of a broader problem, which just happens to have shown up in Turkey first.

In short, is Turkey a canary in the coal mine, succumbing early to an asphyxiation that will go on to choke other developing countries? Ask the question this way, and the answer is: yes, it may well be.

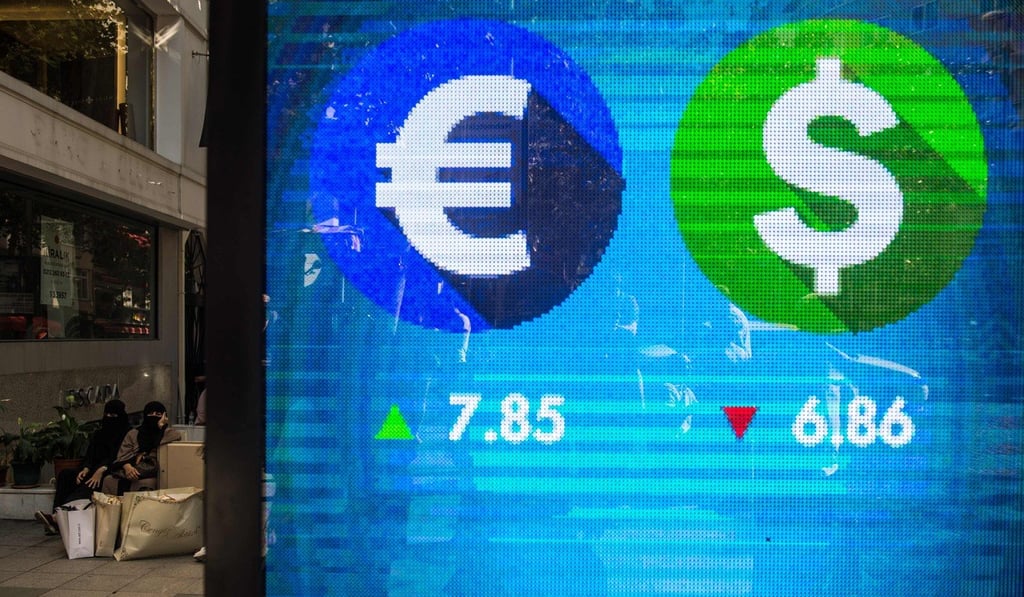

The general perception is that blame for the collapse in the lira, which has lost 35 per cent of its value against the US dollar since the beginning of the year, can be laid squarely at the door of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.