Advertisement

Opinion | What Abe’s China trip means for the Belt and Road – and what Japan has to gain

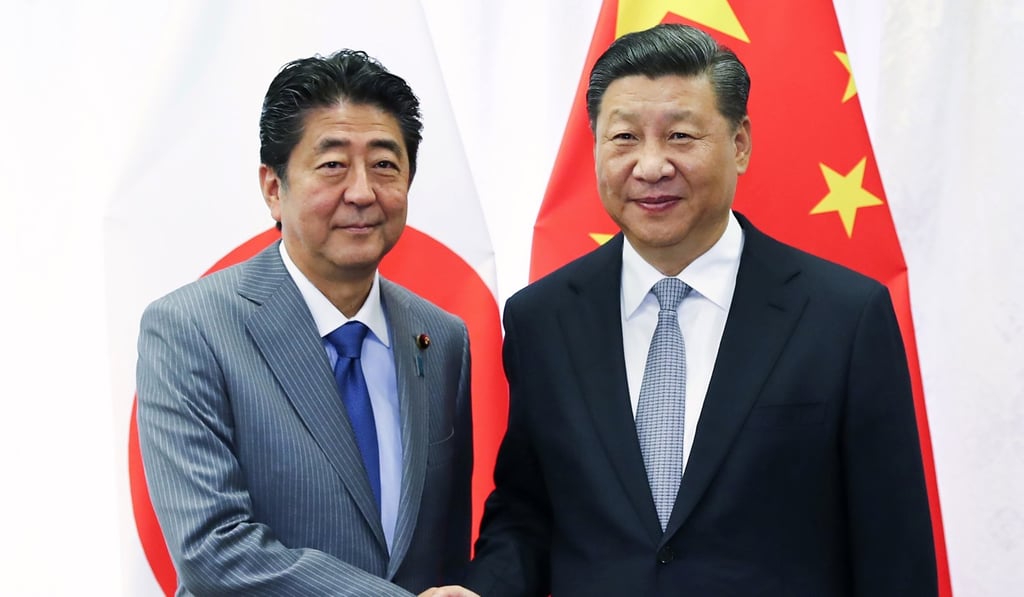

- The prime minister is making the first state visit to China by a Japanese leader in 11 years.

- He and Xi are expected to announce 30 infrastructure projects, signalling a change in approach to the signature development project

Reading Time:3 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

As part of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s state visit to China – the first by a Japanese leader in 11 years – he and Chinese President Xi Jinping are expected to announce 30 joint infrastructure projects.

Of course, there will probably be a raft of other announcements aimed at normalising the political relationship between the two Asian giants that share one of the largest economic relationships in the world, too.

But the most consequential of those may well be the infrastructure deals. That’s because, in welcoming Japan to undertake joint projects, China is signalling a change in approach to its “Belt and Road Initiative”.

Advertisement

Xi’s signature project has hit resistance both at home and abroad, and some of these fears have proved true, with failed projects bringing with them economic and political costs. So, for Japan, engaging with China in this way is pragmatic.

As Chinese policymakers search for ways to better deploy the country’s vast sums of capital abroad, they can draw on Japan’s experience in funding foreign ventures, which dates back to the 1970s. Japan too, suffered a geopolitical pushback.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x