Abacus | Why falling steel prices in Shanghai mean rising smog in Beijing

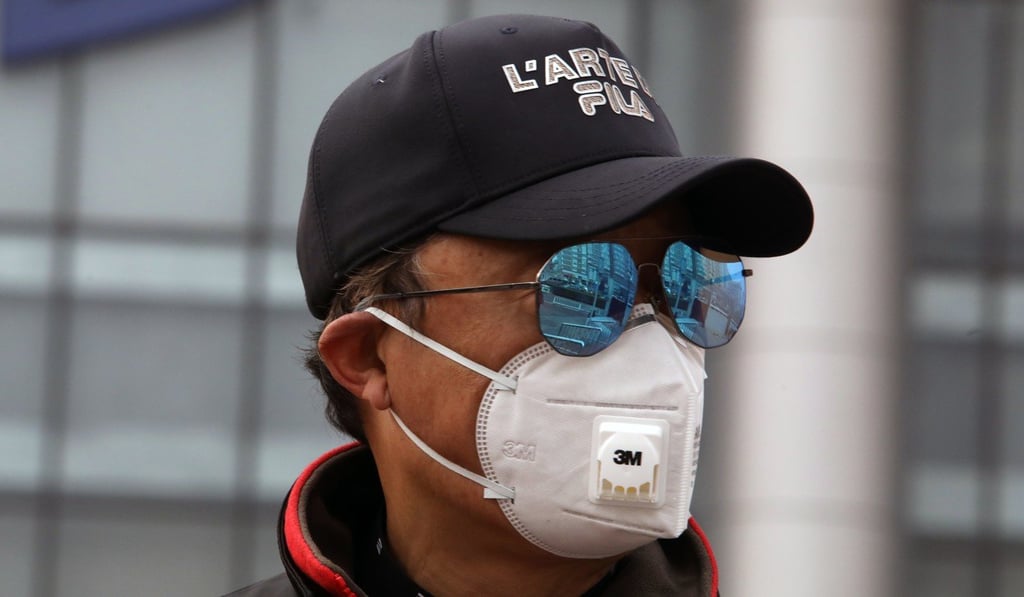

- Steel yourself, there’s bad news for anyone with asthma or who likes to see the Fragrant Hills from their office block this winter

If you want to know whether Beijing will succeed in its ambitious programme to procure pollution-free blue skies this winter across China’s industrial north and east, take a look at the recent price action on the country’s commodity futures markets.

Unfortunately, it suggests China’s toxic winter smog will be back with a vengeance over the next three to four months.

Since late September, the price of aluminium futures traded in Shanghai has fallen almost 9 per cent. Thermal coal futures traded in Zhengzhou are down 14 per cent. And the price of futures contracts on steel rebar – the strengthening metal rods used in reinforced concrete – has slumped by 25 per cent.

For anyone who has a weak chest, suffers respiratory problems, or simply likes to see the Fragrant Hills from the window of his or her Beijing office block on a winter’s morning, this is bad news – even if the link between falling commodity futures prices in Shanghai and rising atmospheric pollution levels in Beijing may not immediately be obvious.

Over the last year or so, China’s leaders have declared cutting pollution levels to be their policy “priority of priorities”. Sensitive to the anger of ordinary people at the health hazards, they have even placed more emphasis on battling pollution than on generating economic growth.