Opinion | We backed Maria Ressa’s Rappler. If you believe in the Philippines, you should too

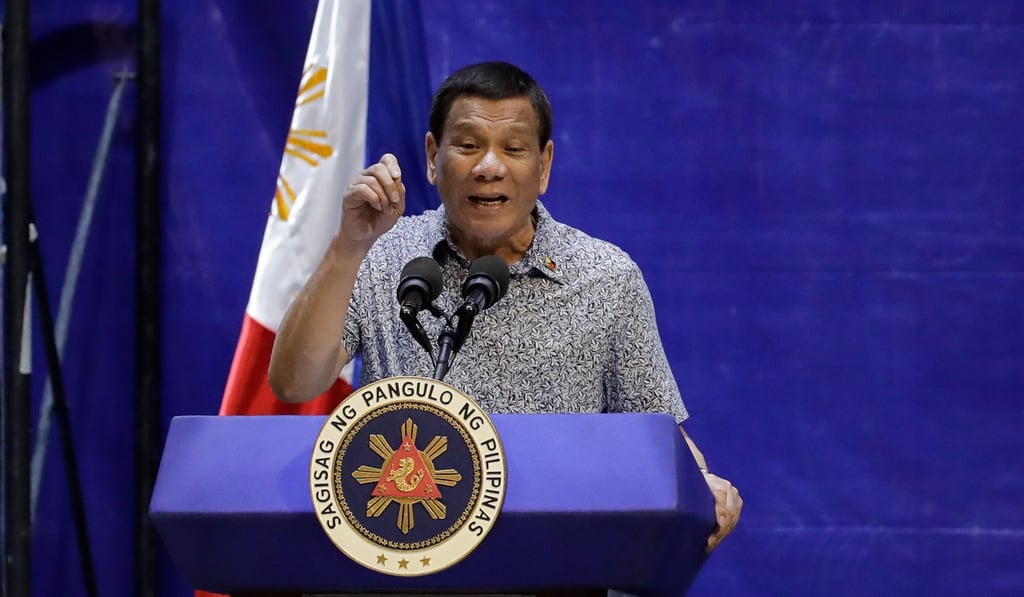

- The Philippines’ commitment to democracy and law is under threat – and Duterte’s watching blithely on, warn the US venture capitalists who invested in the website

It was more than that, though. Maria and her Rappler colleagues saw a civic mission in what they were doing. They organised events for young Filipinos to talk about education, health and politics. They offered live video coverage of political hearings. They let readers react to stories, and then took coverage cues from those responses. When a typhoon devastated part of the archipelago, Rappler deployed a satellite truck not only for covering the news, but to help communities and families to reconnect by giving them access to the internet.

Those killings introduced a phrase into the popular lexicon in the Philippines: “Extrajudicial”, or beyond the law. For headline writers, EJKs – extrajudicial killings – soon became commonplace. Duterte encouraged law enforcement to get rid of drug dealers by any means necessary, and soon journalists were tallying EJKs across the country. By Rappler’s count using the police’s own data, at least 5,000 Filipinos were killed without due process over two years. Various human rights groups peg the number at 20,000.

The government and Duterte’s many loyalists insist that number is exaggerated, a distinction without much moral value, and that many of the deaths occurred in legitimate police actions. But the tide of blood drew the attention of Maria and other journalists, and soon Rappler was publishing carefully documented, excruciatingly painful accounts of what can only be described as state-sanctioned police murders.