‘Di Jihong’ and ‘Gao Jihei’ are signs China’s flattery of Xi Jinping has gone too far

- Going by official media, the intensity of pledges of allegiance to the president were reminiscent of the 1960s heyday of Mao Zedong

- But China’s propaganda apparatus shouldn’t lean too heavily on what has worked before, as the people have grown more mature about indoctrination

In the preceding two weeks, China’s “two sessions” – the annual meetings of the country’s national legislature and the top political advisory body – have gone through the usual but important routine of hearing and approving Premier Li Keqiang’s annual government work report outlining China’s economic growth targets for the year; the budget; statements by the top judge and the top prosecutor; as well as a new foreign investment law.

Throughout the nearly two weeks of meetings, those deputies – from top government officials to lowly village party secretaries – would invariably begin their speeches by praising the wisdom of the central leadership with Xi as the “core”, talking up his “Xi Jinping Thought” political theory or exhorting others to rally around the president before they went on to offer comments on specific issues.

US-China trade war: an elephant in the room for Li Keqiang’s NPC work report

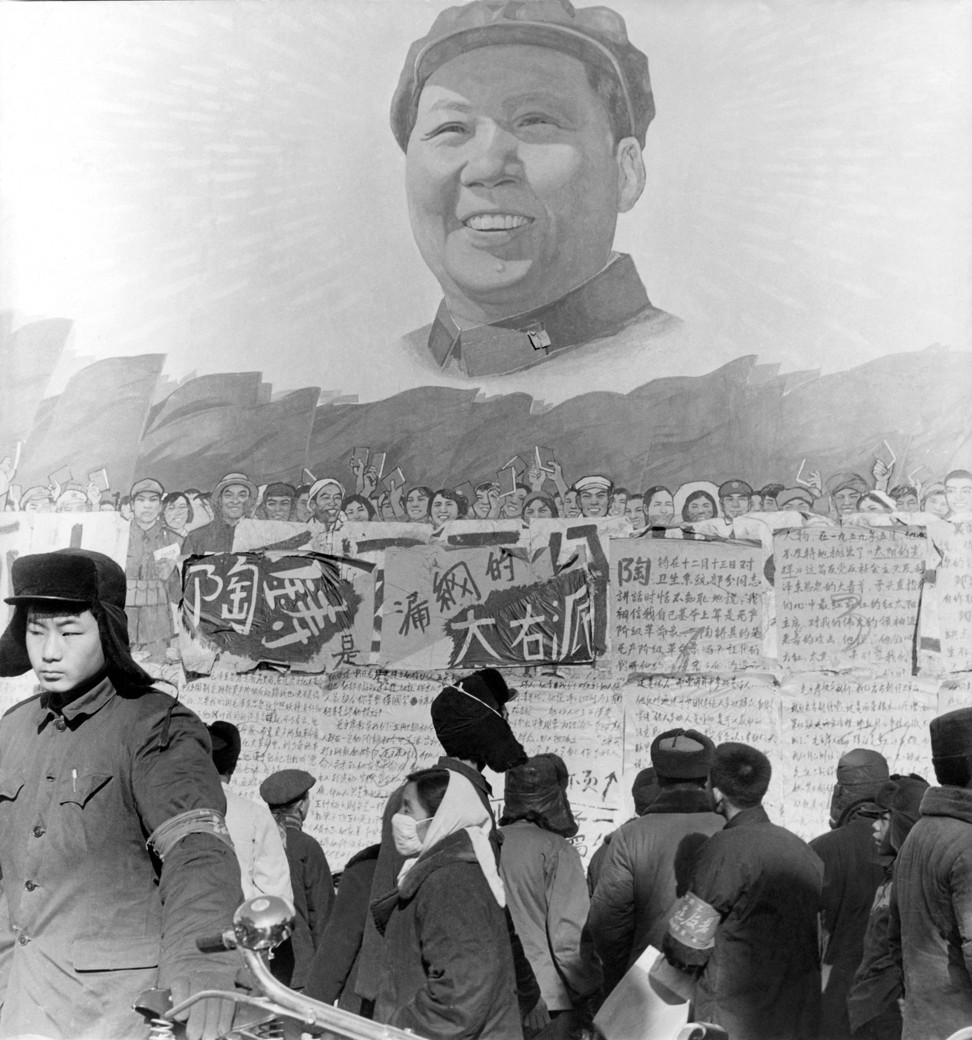

The intensity of these pledges of allegiance was reminiscent of the heyday of Mao Zedong in the 1960s, when the Chinese people even quoted Mao’s aphorisms from the little red book before starting their daily routines.

In an era when Xi is often described as the most powerful leader since Mao, the efforts to build up Xi’s cult of personality since he came to power in 2012 have been truly extraordinary – posters, websites dedicated to his words, courses on his teachings and slick quiz television shows to get the youth studying Xi’s thoughts.

China’s massive propaganda apparatus only needs to dust off the old playbooks and update them for today. But relying on history has its limitations, and doing so can inflict insidious consequences and acute embarrassments on the party and its leadership in this digital age when the Chinese people have grown more mature and sophisticated about political indoctrination.

It is therefore interesting to note that in late February, the leadership, in a directive aimed at “enhancing the political work” of the party, used certain online viral catchphrases: “Di Jihong” to signal its displeasure of any form of low-level naive or ridiculous flattery to praise the party and its leadership, and “Gao Jihei” for high-level sophisticated ingratiation but with a manipulative or sarcastic undertone.

Chinese must live with a dead Baidu, as Google’s return looks doomed

These days the examples of “Di Jihong” are plentiful and easy to spot as eager propaganda officials try to resort to old tricks, which could hoodwink the brainwashed public back in the 1960s but look outright ludicrous today.

The most egregious example occurred in May 2016 when a local railway bureau posted pictures on its website showing a newlywed couple, their employees, spending part of their wedding night copying out the party’s constitution by hand. The activity was clearly staged, with the pictures showing the groom dressed in a suit sitting at the desk writing while the bride in a red gown looked over his shoulder.

The pictures were posted at a time when the party leadership launched a campaign to instil loyalty by requiring each of the more than 80 million party members to transcribe the party’s 15,000-word constitution by hand, among other things.

The photo essay titled “Laying down the paper and copying out the party’s constitution to leave fond memories of their wedding night” immediately went viral, attracting much ridicule and dismay.

Another preposterous example occurred in September 2018 when eager officials in Shenyang, the capital of Liaoning province, installed structures such as British-style red telephone boxes with recording devices inside in public squares and encouraged passers-by to use them to share their “innermost thoughts and feelings” with the party.

There is little doubt those stunts to encourage ingratiation with the party were variations of old tricks that may have worked in the past, but in the present they brought nothing but derision and mockery of the party and its leadership.

Huang Xiangmo and Meng Wanzhou today, any other Chinese tomorrow?

From the party’s perspective, however, the so-called Gao Jihei – more nuanced high-level ingratiation in the form of flattery and opinion conformity – is more dangerous as they could set up the party and its leadership for a fall.

There is no better example of this than the overzealous campaign of the past few years to turn a dusty village in the northwestern province of Shaanxi into a living shrine to Xi.

Liangjiahe was where the Chinese president spent his late teens as a youth, sent to the countryside under a Mao initiative. It was also where – in his own words – he arrived as a confused 15-year-old youngster and left at the age of 22 as a confident young man who had developed a firm desire to serve the people and the party.

Judging from the media reports and Xi’s own recollection, he went through serious hardship, not least because he initially had to share a hard, bug-infested bed with a number of people in a cave home.

During his triumphant return to the village as president in 2015, Xi reportedly told officials and his former village-mates that Liangjiahe might be small but it contained a “profound learning” experience. This suggests that he sees those formative years as a rite of passage that led to his political success.

For local officials eager to show ingratiation and loyalty, they wasted no time seizing upon Xi’s description of “profound learning” as the excuse to launch an over-the-top campaign to enhance his appeal as a champion of ordinary people.

The provincial government transported busloads of civil servants to pay homage to the cave home, senior officials waxed lyrical in official media, and writers, poets and composers were invited to produce a dazzling array of literary works.

As US-China trade war talks enter the final stretch, is Beijing ready to tackle its structural issues?

A provincial think tank reportedly decided to launch an academic study of Xi’s learning experience so as to explore the roots and foundations of the president’s thoughts and his core status as the head of the party and the country.

Not to be outdone, other cities including Shanghai started to invite the villagers to set up representative offices. The drive came to an unceremonious stop late last year after reports suggested that Xi himself thought it went too far. Soon afterwards, a number of senior Shaanxi officials were investigated and detained on corruption charges after official reports indicated they had repeatedly ignored Xi’s specific instructions to probe the illegal construction of luxury villas in the ecologically fragile Qinling mountains.

One of the most senior officials was Qian Yinan, secretary general to the provincial party committee. Before his detention, he was famed for penning a long article heaping praise on Xi and Liangjiahe. ■

Wang Xiangwei is the former editor-in-chief of the South China Morning Post. He is now based in Beijing as editorial adviser to the paper