China Briefing | China’s bids to improve food safety and welfare for its people are just empty words – until the leadership has skin in the game

- The country has had an appalling food safety record over the past decade, with an abundance of public health scandals affecting children

- But as long as the ruling class and elites enjoy special privileges, including parallel food supply chains and health benefits, their vows to improve the system will be found wanting

These range from the infamous melamine-spiked milk powder scandal in 2008, which killed several children and hospitalised tens of thousands of others, to the discovery last year of more than 200,000 faulty vaccines for children.

Chinese parents are constantly on edge because of the alarming occurrence of such scandals in the past, involving unscrupulous businessmen taking advantage of the government’s ineffective regulation and its previous propensity to cover up such incidences.

Hundreds of parents stormed a local school and clashed with police earlier this month when several dozen students experienced stomach pains and were rushed to hospital after eating their school lunch.

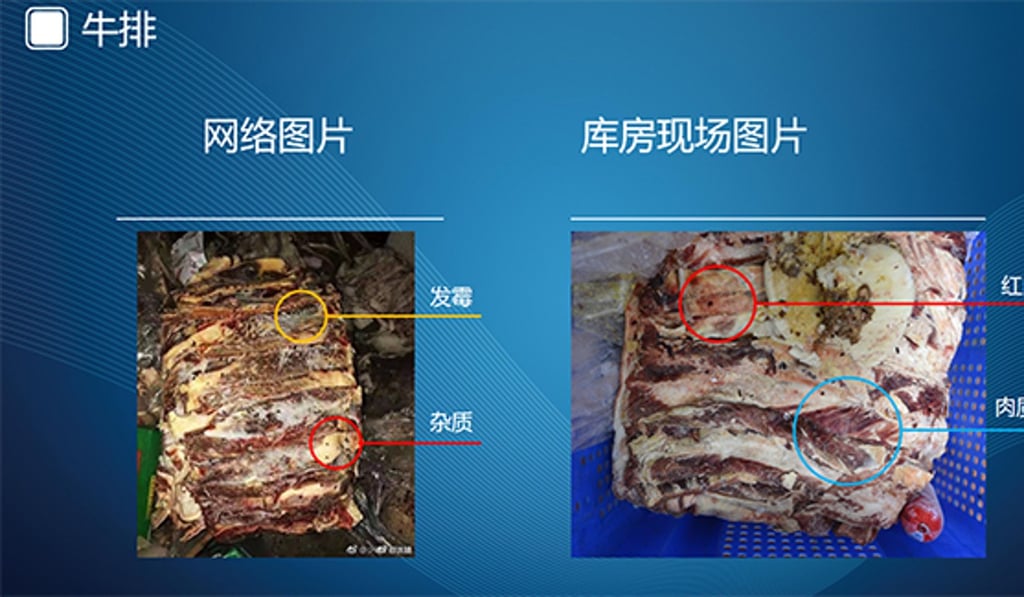

Even though a subsequent government investigation concluded that the allegations of rotten food were largely unfounded, the damage was already done. As the footage of parents protesting and clashing with police circulated online, and because of the people’s inherent distrust of the government’s handling of such matters, there has been a groundswell of anger and concern on the internet over food safety at schools nationwide.