Chinese leaders’ business affairs should be as clear as a US$15,000 crystal horse from Deutsche Bank

- An exposé has revealed Deutsche Bank showered Chinese leaders with gifts, including a US$15,000 crystal horse and a Bang & Olufsen sound system

- It highlights a political taboo – the need for transparency in the business activities of Chinese leaders and their families

On Wednesday, The New York Times ran an intriguing story on its front page on how Deutsche Bank won business in China “by charming and enriching the country’s political elite”.

It is fascinating mainly because the story is based upon internal confidential documents, prepared by the bank and its outside lawyers, that were obtained by the German newspaper Suddeutsche Zeitung.

Over the years, one has heard interesting coffee table rumours about how the multinationals, particularly those international investment banks eyeing big fat fees for underwriting mega initial public offerings of the major Chinese state firms in Hong Kong and New York, had gone out of their way to ingratiate themselves with the ruling elite to get deals.

But this story nailed it because the info came straight from the horse’s mouth in the form of documents that cover a 15-year period and include spreadsheets, emails, internal investigative reports and transcripts involving senior executives. But the focus seems to be on the period from 2002 to 2012.

For Xi Jinping, the biggest danger to the Communist Party is itself

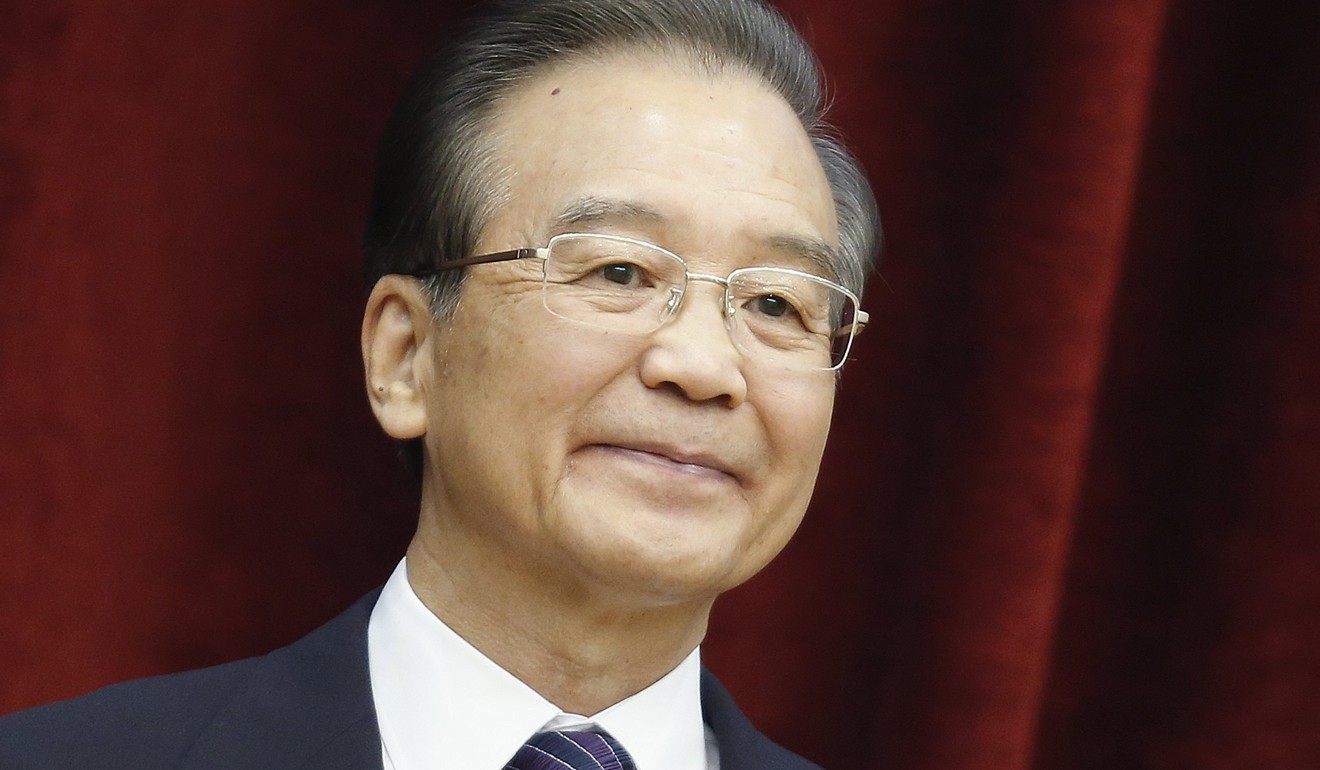

If past experience is any guide, the Chinese government will most likely keep silent over the latest embarrassing revelations, particularly concerning former and current top leaders and their close family members, including the former premier Wen Jiabao and his children.

Well, it should not. Embarrassing as it is, the story once again highlights the urgent need for Chinese leaders to improve transparency and accountability when it comes to regulating the business activities of their children and close relatives – one of the most politically sensitive taboos – and the secretive but immensely profitable business of money for political access in Beijing.

For a start, the story highlighted how the bank had given former president Jiang Zemin a crystal tiger and a Bang & Olufsen sound system, together worth US$18,000, while former premier Wen Jiabao received a US$15,000 crystal horse, his Chinese zodiac animal.

To protect its reputation, the Chinese government should explain what happened to those gifts and make public its rules governing the Chinese leaders and officials receiving gifts from foreign visitors.

Like the United States, the Chinese government has specific detailed rules on gift giving and receiving that stipulate gifts above a certain value should be turned over to the state.

Bearing gifts is peanuts compared to navigating China’s secretive political lobbying world, as the story has well documented.

Unlike in the US and other Western countries where lobbying is legal and heavily regulated, political lobbying in Beijing is largely under the table and behind closed doors.

Because of China’s opaque policymaking process and secretive politics, knowing the right people is crucial for foreign and Chinese companies to secure meetings with policymakers and clinch mega deals. China’s most influential access brokers tend to be close relatives and associates of the senior Chinese leaders.

It came as no big surprise that the bank had paid hundreds of thousands of dollars to those access brokers to secure meetings for its top executives with China’s leadership and advise on the bank’s investments in China.

Why soaring pork prices are a touchy problem for China’s leaders

Influence peddling was particularly rampant in the decade from 2002 to 2012 when Hu Jintao was China’s leader and his weak leadership meant that many powerful political families had built up deep business interests, one of which was that their children or close associates flogged their services as access brokers.

Xi’s anti-graft campaign may have curtailed their business but it would be hard to eradicate it.

In fact, how to regulate the business activities of children and close relatives of senior Chinese leaders has always been a hot political issue in China and often a source of public discontent.

And this issue is not unique to China. For instance, in the US, Hunter Biden, a son of former US vice-president Joe Biden, has been under intense attack by the White House and increasing media scrutiny because of his business dealings in Ukraine and China. In a recent interview, Hunter Biden said he had done nothing wrong but admitted to “poor judgment”, leaving him and his father, a Democrat presidential front runner, open to political attacks.

In China, children of senior officials, collectively known as “princelings”, enjoy the princely treatment that gives them their name at least in part because media reports about their business activities and personal lives are strictly forbidden.

China’s legal system has a long way to go before it can be trusted

Business opportunities started to present themselves after China adopted its open-door policy and undertook economic reform starting from 1978. Many princelings started to dabble in business as they used their parents’ political patronage to profiteer from huge differences between the low prices of industrial or consumer goods set by the government and much higher prices in the private market.

Following the crackdown, the Chinese government shut a number of companies owned by the princelings, including the Kanghua Development Corporation, a conglomerate controlled by Deng Pufang, a son of Deng Xiaoping.

But the strict controls imposed by Deng started to unravel later when the Chinese economy was booming under the leaderships of former presidents Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao from the late 1990s to the first decade of the 21st century.

During that period, China was keen to solicit the help of international investment banks to restructure and prep China’s mega state-owned enterprises for stock market flotation at home and abroad. All the major international investment banks competed to entice the princelings to join their firms so as to leverage their parents’ political connections.

But seeking a well-paid job at an international investment bank was less controversial. The more aggressive business-oriented princelings used their connections to make big money across a wide spectrum of sectors, from land development to fund management.

Many of the officials netted in Xi’s anti-graft campaign had wives and children who were also accused of profiting from their power.

To be sure, over the years the Chinese government has reportedly released a raft of regulations to govern the business and investment activities of senior officials, including requirements that they declare their business interests through internal channels.

But as the Times story has shown, such measures have had little effect. Over the years, there have been consistent calls for the government to allow senior officials to declare their own assets and those of their close relatives publicly, in line with international practice.

This month, the party’s leading theoretical journal Qiushi (Seeking Truth) published a lengthy excerpt of a speech Xi gave to a group of senior officials, warning about the long-term and complex challenges the party faced.

Among the challenges, he said, privilege was the biggest injustice. He urged senior officials to maintain high self-discipline and exercise better supervision of their relatives and people who work for them.

More transparency and better public scrutiny would definitely help achieve the goal. ■

Wang Xiangwei is the former editor-in-chief of the South China Morning Post. He is now based in Beijing as editorial adviser to the paper