Advertisement

Opinion | Can Japan persuade Southeast Asia not to break the rules-based order as China dangles cash?

- Japan needs global rules to prosper; China has shown a willingness to break them

- Now Tokyo is stepping up engagement with Southeast Asia in an effort to ensure regional states don’t do the same

Reading Time:5 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

“Japan will offer its utmost support for efforts by Asean member countries to ensure the security of the seas and skies and rigorously maintain freedom of navigation and overflight.”

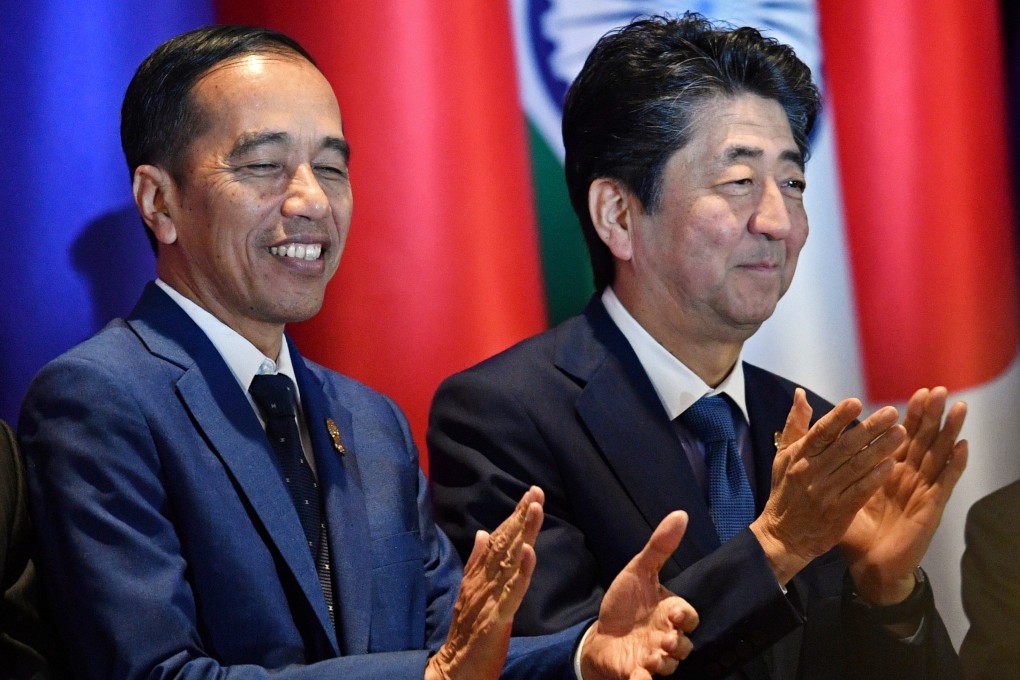

So said Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in his keynote speech at the Shangri-La Dialogue in 2014.

The pledge was part of his commitment to the Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy touted by the United States and Japan and unveiled in 2016 in the face of rising challenges to the international rules-based order established after World War II.

Advertisement

Nowhere is this order being challenged more than in Southeast Asia.

China’s nine-dash line claim to exclusive sovereignty in the South China Sea not only brings it into conflict with the territorial claims of other coastal states, but also repudiates freedom of navigation under international law.

Beijing’s assertive use of its growing maritime paramilitary and naval power to enforce its claimed governance rights threatens the maritime security of other states, as well as regional stability. Spearheaded by its Belt and Road Initiative, Beijing is accompanying its territorial push by cultivating excessive economic control and dependence in partner economies in the region.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x