Asian Angle | Think 2020 is weird? Spare a thought for 1010: a frozen Nile, ‘giants’, killer Vikings and a Farsi Game of Thrones

- With all the craziness of life in 2020, what better time than now to look back a thousand or so years and find out what was making the headlines in 1010?

- Amid a warmer climate and a short-lived Pope, Rob McKenzie uncovers Viking slaughters, a cold snap in Egypt and some surprisingly tall Swedes

As 2020 dawned I had an idea for an article. I wondered what it would be like to look back at the year 1010: halfway between the birth of the Common Era and now. Were people happier and wiser, or benighted and foolish? It would be fun.

My idea had been to take our present-day torrent of news, all the momentarily urgent matters that are forgotten when the next wave comes along, and contrast it with the distilled events of 1010 to provide a smidgen of perspective. But now, even as the many waves have given way to one big wave, the deep breath of perspective remains useful. So let us consider 1010, and see what we might learn.

First, a quick fly-by of the state of the world in 1010: the tallest structure on Earth was the Great Pyramid of Giza, already 35 centuries old. The global population was somewhere around 300 million. The Northern Song dynasty reigned in China; the Mayan civilisation in Central America was in its long decline; the Caliphate of Cordoba was beset by infighting. In Rome, the Pope was Sergius IV, son of a shoemaker – he served three years as pontiff and the cause of his death might have been murder. And backtracking the slow grind of plate tectonics, America and Europe were about 25 metres nearer one another, and ocean levels about 360mm lower.

Now let us look at four of the headline stories of 1010 and see what light they might cast on the present day. They concern climate, Vikings, the relationship between cities and human height, and fantasy literature.

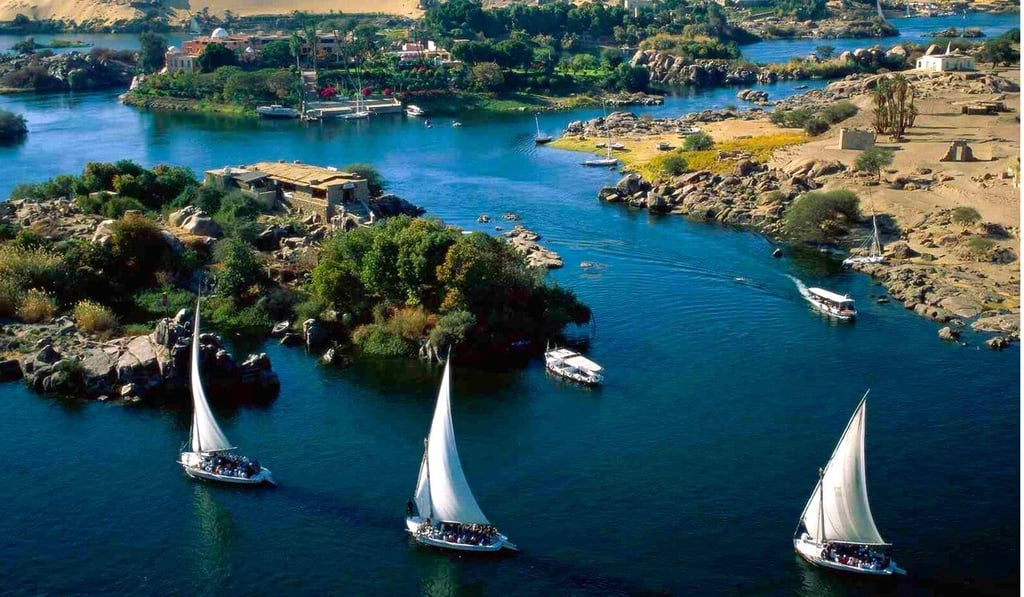

1. NILE FREEZES AS COLD SNAP SLAMS CAIRO

The natural world provided the most startling newsflash of 1010: for though this was the Medieval Warm Period in much of the world, in Egypt the Nile froze for only the second time in recorded history – the first being in 829.