On Reflection | After the coronavirus: could the US collapse within the next year or two?

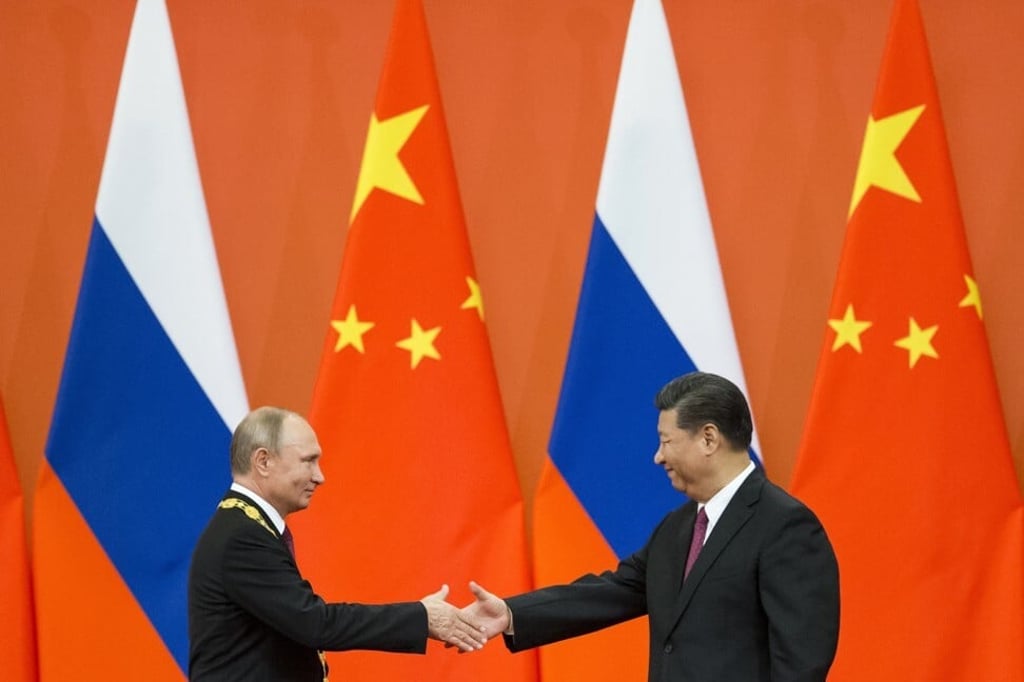

- Three disaster scenarios beckon if Trump, Xi and Putin can’t work together in the post-Covid-19 world

- Even war cannot be ruled out in the event of an existential political threat to any one of these leaders

Perhaps leaders in Britain, Canada, France, Germany, India or Japan will step in to save the day, but this can only be a partial save in the best case, given the huge disparities in size and capabilities between these secondary powers and the “big three”.

Answer: There are three. They are all bad taken on their own, and horrific in any combination. Let us all pray that we do not get there.

The most probable and nearest-term consequence of trilateral discord will be an acceleration and deepening of parasitic regulatory competition between US-led commercial and trading spaces and Chinese-led spaces, with Russia, by far the weakest economic player, tilting ever more intensely towards the Chinese spaces and attempting to exert, with growing ferocity, regulatory control over at least 12 of the 15 post-Soviet states.