How the coronavirus pandemic could lead to a ‘less Chinese’ belt and road initiative

- As the physical connectivity aspect of the belt and road plan takes a hit amid the Covid-19 outbreak, health and e-commerce projects may get greater attention

- To spread risks, China may have to work with partners such as the World Bank or Asian Development Bank – a move that could boost trust in the initiative

To soften the blow on countries taking part in the initiative, Beijing has already suspended debt repayment. In addition, while outright debt cancellation is not on the table or reserved as a least desirable last option, China is exploring other avenues such as interest payment suspensions, relief, or restructuring. Given the diversity of participating countries, this will be handled on a case-by-case basis.

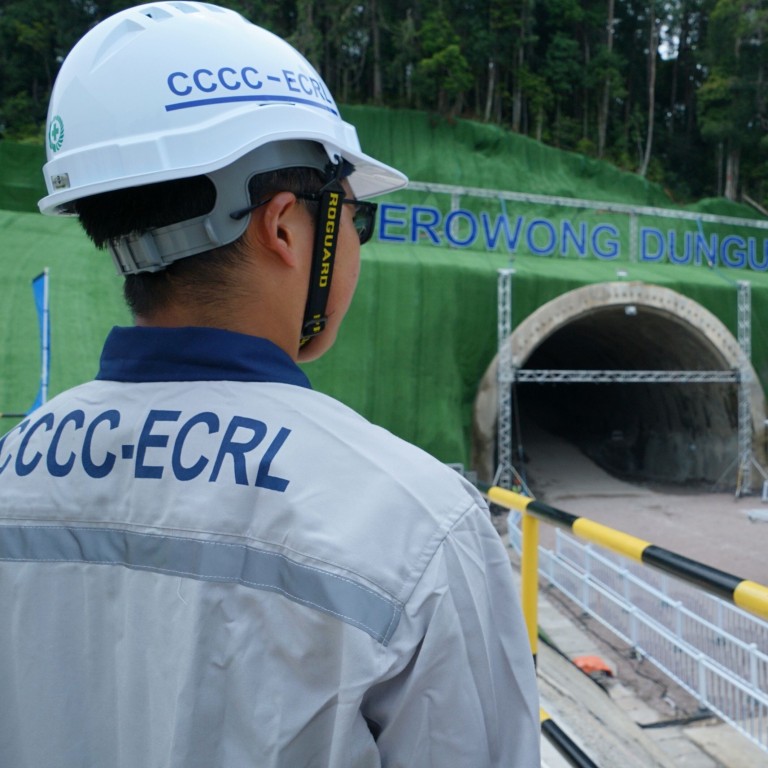

The quicker the world recovers, the better traction for the belt and road strategy. The easing of lockdowns and travel restrictions will restore supply chains and recommence work on infrastructure projects across the region – but resumption will not be geographically even. It is likely to begin in Southeast Asian countries that were ahead in containing the coronavirus. The East Coast Rail Link project in Malaysia, for instance, resumed last week. Some projects like the China-Laos railway, however, were not halted by the pandemic. A third tunnel along the Jakarta-Bandung high-speed railway project was also completed late last month.

That said, delays and disruptions will temper China’s ambitions. Ongoing belt and road projects will be pushed through, but those under negotiations may be deferred and no new proposals are likely to be introduced in the short term.

China’s belt and road: after the gold rush, Pakistan sees the downside

While its physical connectivity component will take a hit, other facets of the belt and road plan, such as the health and digital strands, may get greater attention, though not without issues. The pandemic will enhance calls to coordinate, if not harmonise, health and quarantine regulations and promote medical and scientific cooperation along the route.

China and Indonesia’s fruitful, complicated relationship 70 years on

The Health Silk Road, a conduit for fostering health cooperation among participating countries that leverages existing transport connectivity, could have capitalised on this. But China’s bungled initial response to the outbreak and quality issues on Chinese-made medical supplies undermine Beijing’s legitimacy on this front. Tougher export quality control measures must be instituted.

Likewise, with more people staying at home and work and school going virtual, mobile and online commerce may get a big boost. This may present opportunities for e-commerce and fintech firms. But security concerns raised in relation to working with Chinese technology companies such as Huawei, Tencent and Alibaba may present hurdles for them in expanding business to other belt and road initiative countries. Winning trust is critical for China to seize a greater share of emerging belt and road markets.

Efforts along these lines already began pre-pandemic and are likely to expand further. This includes China and Japan third-party market cooperation and co-financing between the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and other multilateral lending institutions like the Japan-led Asian Development Bank, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and the World Bank.

More than bringing in experience and expertise, getting more external partners can also improve project acceptability. Such a consortium may elicit less public opposition compared to solely China-backed projects. The pandemic may also increase demands for more local content – labour, experts and supplies – whenever capacity meets agreed standards.

As calls for more self-reliant supply chains resonate, participating countries may also demand greater knowledge, skills and technology transfer. This will contribute in making the belt and road strategy a more sustainable initiative instead of one that engenders dependence.

Lucio Blanco Pitlo III is research fellow at Asia-Pacific Pathways to Progress Foundation Inc.

Help us understand what you are interested in so that we can improve SCMP and provide a better experience for you. We would like to invite you to take this five-minute survey on how you engage with SCMP and the news.