George Floyd death: China is right to criticise the US on race. Next step, more Uygurs on politburo

- When America aspired to being a beacon to the world, global pressure on its race record – including from China – helped drive it to change

- If China wants to be a global power too, it must accept that internal politics are open to outside criticism

Newton was not the first Panther to visit Beijing; his colleague Robert F. Williams spent several years there, as detailed by the historian Matthew D. Johnson. Earlier, one of the great African-American intellectuals, W.E. DuBois, had been a guest of the PRC at the age of 91 in 1959.

In those days, China was certainly happy to host and praise critics of the leading country in the West, even when, as with the Panthers, those critics were committed to violent overthrow of the existing order.

America in the 1950s and 1960s was undoubtedly the most influential society on the globe. The world flocked to its universities, looked on awestruck at its technology and hungered for its lifestyle, its society underpinned by a commitment to one value above all: freedom.

Yet that freedom had at least one deep and hypocritical element within it: the US’s appalling record at home on race. A century after they had been supposedly freed, African-Americans still suffered legal discrimination in the states of the south, filled America’s prisons well in excess of their proportion of the population, and were policed, not protected, by law enforcement.

There is an excellent argument that until the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the US was not a full democracy. Yet America’s conservative elites, both Southern Democrat reactionaries and renowned Republican intellectuals like William F. Buckley, argued this was no business of anyone except Americans (and white Americans, at that).

At the Oxford Union in 1965, Buckley even criticised the great black writer James Baldwin for criticising the US in front of an audience of foreigners.

01:17

China urges US to tackle racial discrimination as violence follows police killing of George Floyd

The American argument that nobody except Americans could have a view on its racial record was humbug and it couldn’t last, for one simple reason. No country could aspire to be a beacon to the free world, as the US did, and still suggest that gross, legal discrimination on its own soil was acceptable.

Certainly China did not buy that argument: the visits of DuBois, Williams, and Newton to Beijing were in large part to point out American hypocrisy – and rightly so.

China and Britain: two countries out of touch with the post-Covid-19 future

Chinese official reactions were swift and clear; what happened to the Uygurs was purely a matter of Chinese internal politics and of no concern to any outsiders.

But the argument that China’s internal politics were not the business of the world became irrelevant when China decided that it wanted to become a global leader. In terms of economics, security, finance, China has chosen to go global; it boasts, with justification, of its record in poverty reduction in the past 40 years as a token of what it can contribute to the world. But if that particular internal matter is of relevance to the world, so is its record on race.

Spokespeople’s response to that challenge is generally to say that China is unlike America because it doesn’t seek to change anyone else’s ideology. But that ignores one reality: you don’t get to define yourself as a global power. America wanted to be seen as a beacon of freedom, and in many senses, it was.

But the wider world was right to point out where the US fell short (and is right to do so today). Chinese officials boast regularly of the “China model”. National models by definition need foreign imitators. In which case, they also need foreign critics.

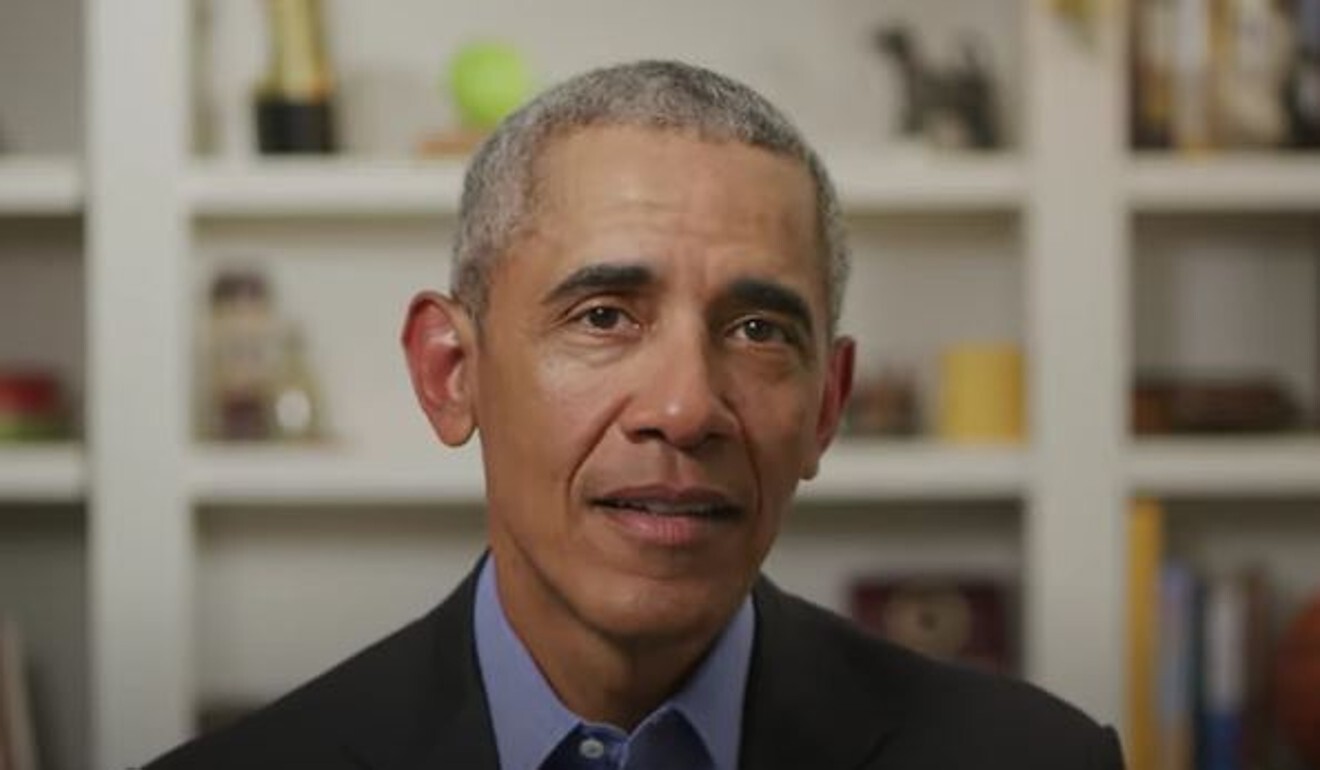

One of the best counterarguments that the US was able to make about the world’s criticism of its record on race was not just to complain, but instead to change society painfully but thoroughly so that in two generations, a black woman could become Secretary of State, and a black man could become President.

China has 56 ethnic minority groups, including the Uygurs. Get more of them on the Politburo. Appoint many more of them as ambassadors to the West. And make diversity not a source of sarcasm about why America is worse, but instead a source of pride about why China does it better.

Rana Mitter is Director of the University China Centre at the University of Oxford and author of A Bitter Revolution: China’s Struggle with the Modern World and China’s War with Japan, 1937-45: The Struggle for Survival