From Indonesia to Hong Kong to Singapore, an ongoing battle against racist stereotypes

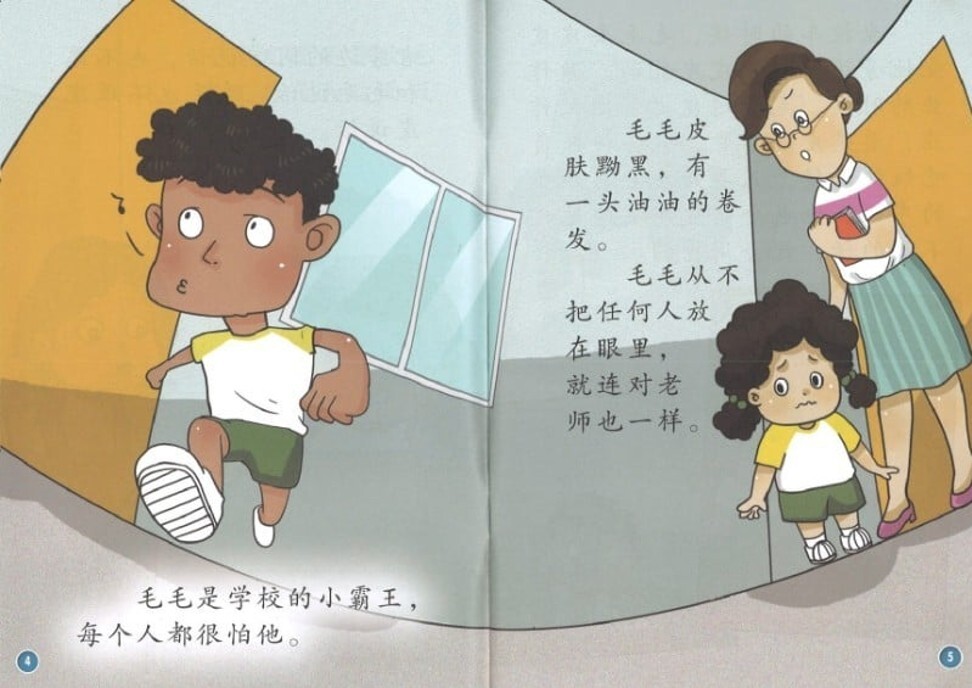

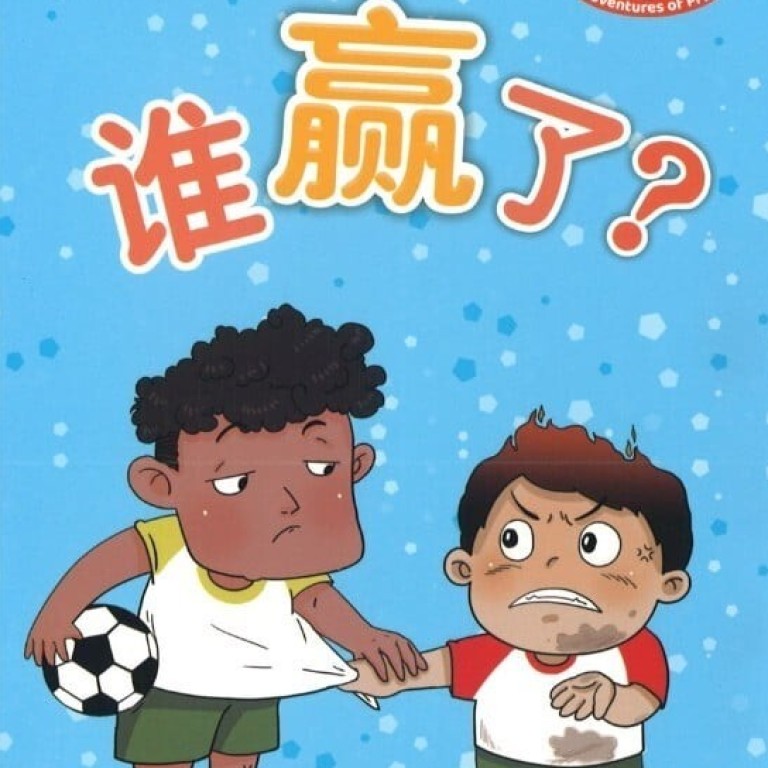

- A Singapore children’s book depicted a school bully as dark skinned while other pupils were fair. It’s just one of many racist tropes in media and literature

- Psychologists say even simple images reinforce unconscious biases that if left unchecked, are of great detriment to society

Marshall Cavendish Education said it had no intention to “produce content that promotes discrimination in any way”.

Its response came after a Facebook user asked what “possessed” the publisher to print a book where the “sole dark-skinned character is irredeemably nasty – especially when his appearance is irrelevant to the plot?”.

Beware rise of technology-fuelled racism in Asia: UN report

The user had earlier returned the book to the public library with a note stating her concerns and the National Library Board immediately removed all copies of the book from its shelves, pending a review.

An internet search for the book, titled Who Wins by Wu Xinghua, showed it was in the collection of at least one school library, while another listed it as recommended additional reading for children in 2018/19 by Singapore’s Committee to Promote Chinese Language Learning.

The committee, currently led by a member of parliament belonging to Singapore’s ruling party, has not commented on the book.

In discussions of the episode, minority race Singaporeans have recalled the playground slurs and schooltime jeering they experienced on the basis of their skin colour.

There have also been questions on how the book’s offensive and harmful racist stereotypes passed through the series of editorial checks that are supposed to happen before publication.

Similarly, did civil servants and educators involved in stocking shelves of public and school libraries, or the personnel producing reading recommendations, review the publication beforehand?

White privilege: to dismantle it, we must first learn to identify it

Incidences of racist stereotypes perpetuated by majority groups, whether inadvertently or due to misguided beliefs of superiority, are not unique to multiracial Singapore, though this does not negate the pain and discomfort felt by the city state’s ethnic minority communities when they occur.

Radius Setiyawan, a doctoral student at Indonesia’s Airlangga University, recently wrote in online platform The Conversation that films, television shows and school texts featuring indigenous Papuans – who are ethnic Melanesians from Indonesia’s easternmost provinces – had institutionalised negative ideas about the community being “primitive, stupid, [and] poor”.

To “break the chain”, the government would need to pay attention to what children were reading and watching, while parents had to make them aware of racial sensitivities, he says. This was needed to avoid a situation where they might grow up to develop biases that could lead to racist or discriminatory behaviour, or worse, violence.

03:13

Black Lives Matter protests held across Asia

Similar examples of racist tropes perpetuated in publications and the media can be found across the world, affecting minority communities including black populations and ethnic Chinese in the Western world.

The negative ramifications of unconscious racial biases and how they are shaped have been well-documented by academics, including Stanford psychologist Jennifer Eberhardt, whose research has shown that police are more likely to identify African-American faces as criminals, compared to white faces.

Beyond the pale: why is Asia so hung up on skin tone?

Some Indonesians adapted the hashtag to #PapuanLivesMatter to call attention to the treatment of Papuans by police and the military that critics describe as more brutal and shaped by racism.

In Hong Kong, where South Asians are among the largest ethnic minority groups, along with Filipino and Indonesian domestic workers, activists reiterated how biases have led to racial profiling of minorities by the police. For example, people of South Asian and African descent are more likely to be stopped and frisked than ethnic Chinese.

Colgate reviews Chinese toothpaste brand Darlie amid US racism debate

Eberhardt, in an eight-minute presentation posted on YouTube in June, says biases, which are markers of our history and what we’ve seen, are not always bad.

They are what informs us to “approach the house pet but leave the wild animal alone”. But left unchecked, unconscious biases can lead to great detriment for social groups and the world, she says.

Biases are notoriously easy to form but equally difficult to erase. Simply seeing images can “intensify stereotypes” and shape “beliefs and feelings” we attribute to others, Eberhardt says. They will not necessarily be shaken off even if one leaves the society where those beliefs first emerged.

As she put it: “People often say, seeing is believing. But in many cases, believing is seeing.”