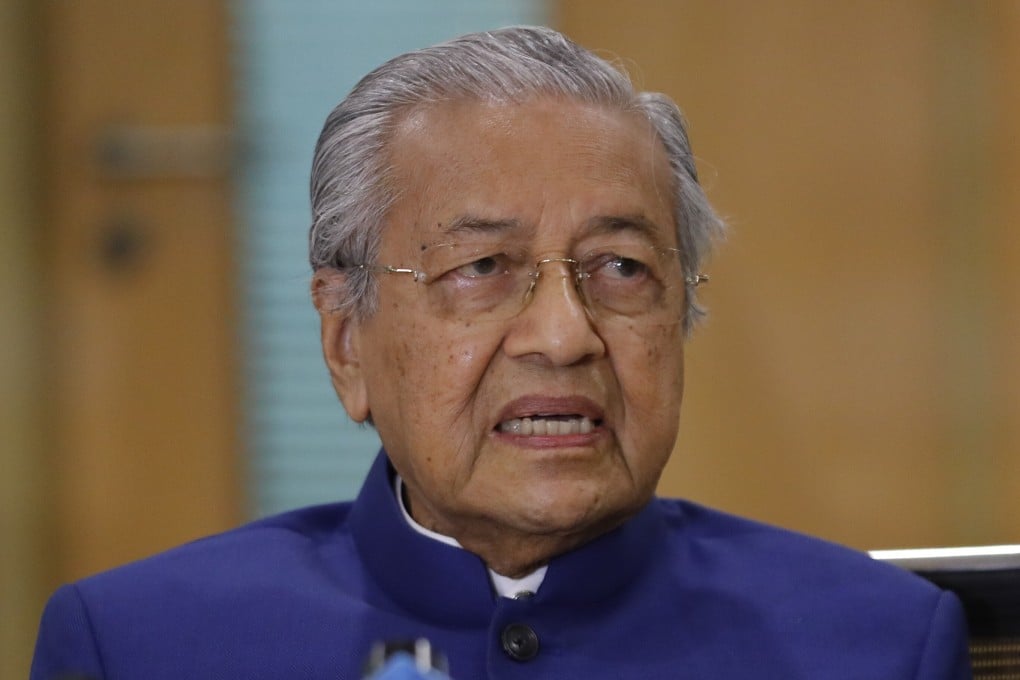

Opinion | Mahathir’s last battle? Malaysia by-election set to test support for former PM’s new Pejuang party

- The long-dominant Barisan Nasional is tipped to win Slim, but support for both it and Umno has been on a downward trajectory there for years

- Mahathir Mohamad’s new party is also in the running – with its performance seen as a key test of the former PM’s lasting appeal among rural Malays

On Saturday, the residents of Slim – a small, rural, Malay-majority constituency in the Malaysian state of Perak – will vote in a by-election.

The by-election will also be a test of the internal cohesion of the expanding Muafakat Nasional coalition – which began as a team-up between Umno and the conservative Islamic party PAS – as well as the Pakatan Harapan grouping that ruled the country from 2018 until its ousting earlier this year.

Electoral battleground

Perak is one of Malaysia’s largest, more diverse and politically important states – home to an estimated 1.2 million registered voters and 24 parliamentary seats. Since 2008, it has been an important electoral battleground, with the opposition securing the state government on two occasions, in 2008 and 2018.