Advertisement

Asian Angle | China and friends surround India. Your move, New Delhi

- With massive investments in Pakistan and Myanmar, China’s influence extends along India’s western and eastern flanks

- Delhi feels threatened, but it needn’t. China wants peace, stability and an inclusive relationship. Only India can decide if it does, too

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

The recent visit of China’s top diplomat Yang Jiechi to Myanmar stood out as the first high-level visit between the two countries since the outbreak of the coronavirus.

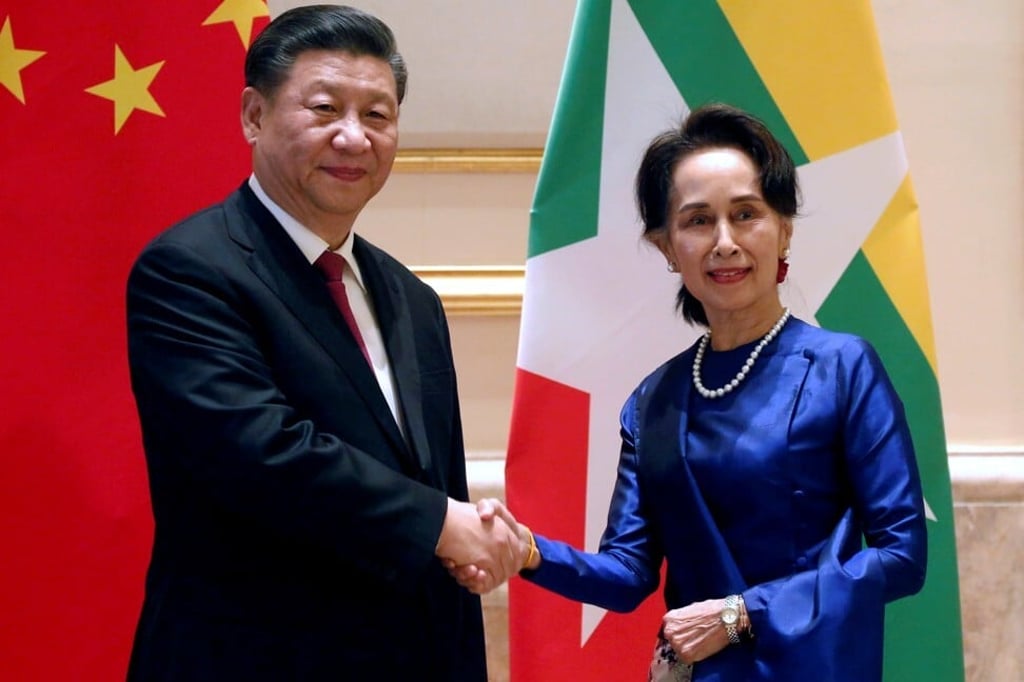

It was the second state visit by Yang since he began a diplomatic charm offensive with a trip to Singapore on August 19 and followed a visit by President Xi Jinping half a year ago in which dozens of cooperation agreements were agreed.

It also comes at a significant juncture; Myanmar is to hold a general election in November and it looks likely that Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy will be returned to power.

Advertisement

Such high-level contacts between China and Myanmar are a reflection of a relationship that has been strengthening in recent years.

Advertisement

For Myanmar, China is not only its largest trade partner, its main source of foreign investment and assistance, but it is also a diplomatic shelter in the international arena. For instance China, together with Russia, has protected Myanmar from UN sanctions proposed by the West as a response to Myanmar’s alleged involvement in human rights abuses against the Rohingya.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x