Hong Kong’s young people can be trusted with the city’s future. Give them a stake, and a chance

- The city needs economic diversification, and young Hongkongers can play an active part in its development through sharing the responsibility for change

- But there need to be more avenues where they can set the agenda and determine priorities for the good of their neighbourhoods and districts

But while this is a good start, Hong Kong must also start to share the responsibility for youth development with the city’s young people. Giving them a stake in designing Hong Kong’s future – and helping them feel that this stake actually means something – will help to counter feelings of disillusionment and resentment.

Leaving Hong Kong isn’t the answer. Staying and building a new one is

For a start, Hong Kong could and should play an important role in national, regional and global initiatives, such as Beijing’s pledge to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. This policy could be truly transformative if the opportunity is captured, and enough people are willing to reimagine the city. But school trips and mandated curriculum are not going to encourage young people to buy into these projects. Instead, Hong Kong needs to start handing the ropes to up-and-coming young leaders … and not just the usual well-connected suspects.

Hong Kong, like many advanced economies, has a young population dissatisfied with the status quo, who worry about limited job prospects, instability, and a narrowing path to a good standard of living. But a pure economic framing misses the point that youth discontent is also driven by the sentiment that their interests are not represented in politics and policymaking.

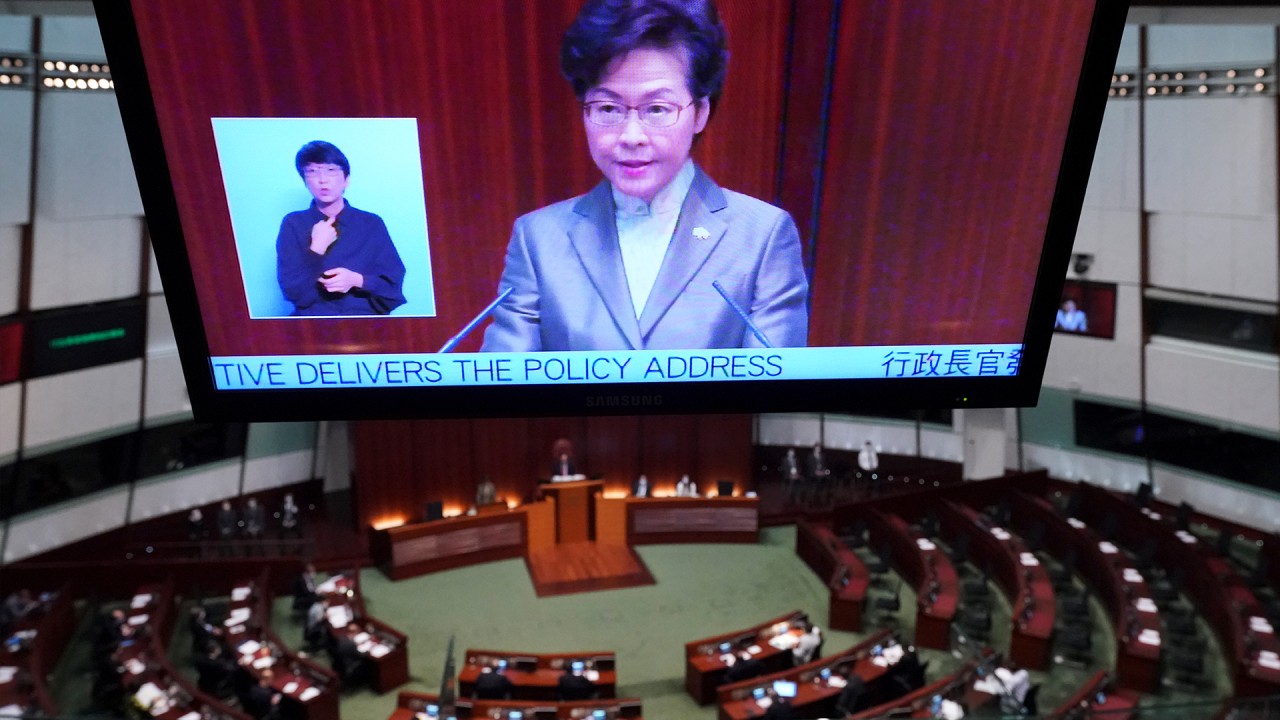

04:47

Hong Kong leader Carrie Lam delivers 2020 policy address

After all, we can agree that the city’s success has also created a conservative status quo in key economic areas. From climate change to higher education, the interests of younger generations – an age range, in practice, that spans recent school graduates to parents in their early 40s – are seen to be neglected at a time when we need to revolutionise the economy with a view to its role, and the needs of the people, over the next 20-30 years.

With adequate support and guidance, the bright and hardworking young people of this city can develop practical ideas that can resolve Hong Kong’s problems.

Over the past few months, I have had the great privilege of working closely with two groups of young people, listening to their thoughts about the city and helping them develop practical ideas for the future. These young people cross age ranges, employment backgrounds, educational levels, incomes and ethnicities. Importantly, they want to stay in Hong Kong, and help build a more diversified economy.

These young people were asked to do a lot in just a few weeks. We gave them a meaty problem – diversifying Hong Kong’s economy and creating new jobs for the city’s youth – asked them to do independent research, then drove them to develop actionable ideas that the city’s leaders could take forward.

Take the creation of an energy-efficiency market and a mandate that buildings disclose their energy usage. This would give real meaning to the idea of using tech to create a smart city. Buildings that undergo retrofitting procedures to improve their efficiency would be rewarded for these efforts, while those that lagged behind would be charged. This would create a working market in energy efficiency, contributing to Hong Kong’s stated objective of achieving carbon neutrality by 2050. The same could be done with the management of solid waste and waste water, with revenue raised from waste charges going to an SME green fund which could be tapped by youth entrepreneurs keen to build a “green economy.”

Another idea was making Hong Kong into a regional cold-storage hub. The Covid-19 pandemic, and the need to transport vaccines in very cold temperatures, highlights the importance of this capacity. A hub would become an integral node in supply chains between China, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean), and the wider world. It would draw on Hong Kong’s core strengths, such as its legal system and logistical infrastructure. This could potentially create thousands of jobs and catalyse growth in big data systems, analytics, and testing/certification.

These young people also studied issues that are less thought about, and don’t make the headlines.

For example, Hong Kong is one of the world’s most food-vulnerable places, due to its reliance on food imports. Investment in local food production would bolster the resiliency of the city’s food systems, while also opening up new job opportunities. Such a plan would strive to reduce food imports by some target date, encourage local growth of staples and other food products, and use the latest technology and science to convert a range of available spaces into “food gardens”.

The US fears competition. Its status as head of the global order must now be rethought

Another issue is ageing: Hong Kong’s elderly population is expected to reach 2.1 million people by 2029, and currently the city only has one carer for every 7.5 elderly. A care agent scheme was proposed to train new carers working in registered elderly centres, highlighting the value of these careers to upcoming graduates. A neighbourhood service scheme would also knit together generations in a single area, perhaps helping to heal the generational divide within Hong Kong society.

These are just a few of their ideas, with proposals ranging from sports/well-being hubs run by young people to a youth community service scheme – backed by the government and the private sector – that would provide certifiable on-the-job training for periods ranging from one to three years. And while there is still work to be done to develop them further, these proposals are just as good as many of the ideas proposed by previous generations.

Young people should be trusted to not just take Hong Kong’s issues seriously, but also do the work to propose solutions. But there need to be more avenues where they can set the agenda, determine priorities, and implement solutions for the good of their neighbourhoods, districts and cities. The government, working with the private sector, needs to support the creation of these well-managed and well-facilitated platforms.

Chandran Nair is the founder of the Global Institute for Tomorrow and a member of the Club of Rome. He is also the author of The Sustainable State: The Future of Government, Economy and Society