Opinion | Why China sees difficult choices in Myanmar’s political realities

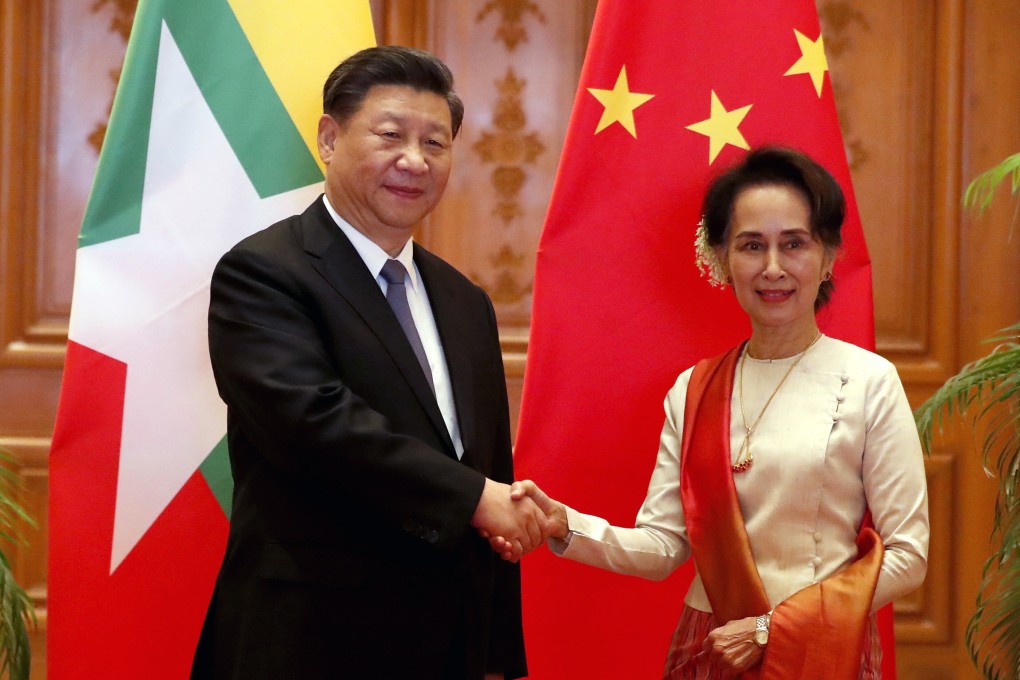

- It is inconceivable that Beijing would have supported a coup; in fact it worked well with democratic icon Aung San Suu Kyi

- Two factors will haunt China’s calculations as it navigates Myanmar’s new politics, says Yun Sun

While this position is neither new nor surprising, it has a fully justified internal logic. However, Myanmar’s unexpected political developments will inevitably introduce challenges and uncertainties for bilateral relations down the road.

Geographical proximity, as well as the pair’s comprehensive and complicated historical, ethnic, political and economic ties, mean that whoever is in power in Naypyidaw will want to maintain a positive relationship with Beijing.

As such, China has been the most consequential external player in Myanmar’s key political and economic events of recent years, including its ethnic reconciliation process and economic growth.

01:16

Myanmar junta leaders hold first meeting of military government the day after staging coup