China Briefing | If China’s leaders want to engage the international media, learn from Mao, Deng and Jiang

- China must do more to engage international journalists if it is to answer Xi Jinping’s call to develop an international voice that will make friends and influence people. First, it must let them back in

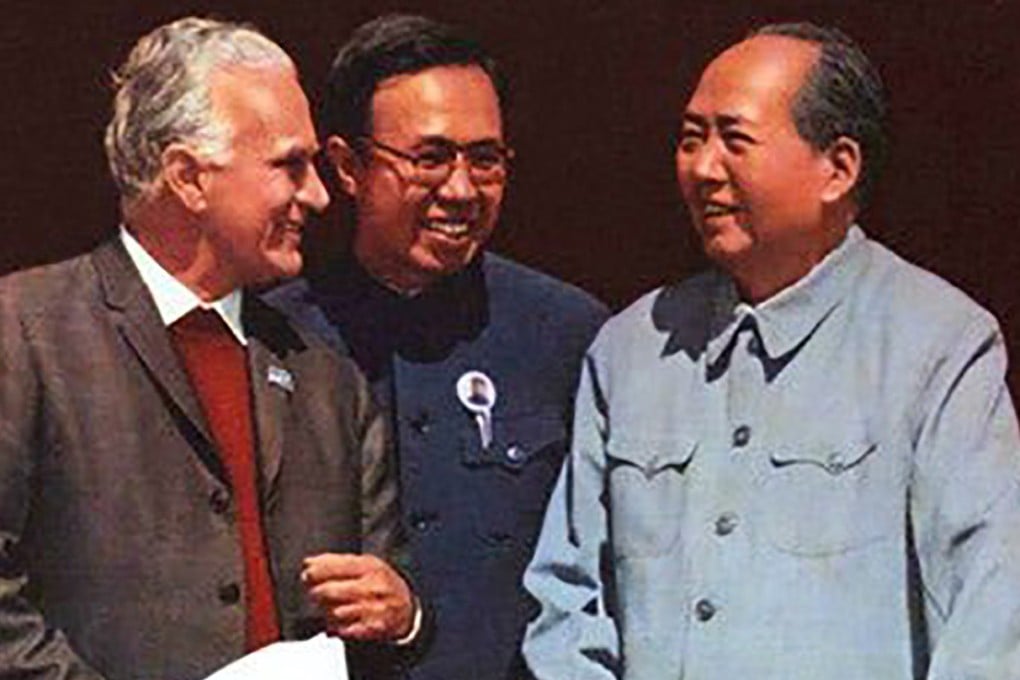

- Mao’s relationship with Snow, Strong and Smedley was a media masterclass; as was Deng’s two-day interview with Oriana Fallaci; and Jiang’s tough 60 minutes with Mike Wallace

Back in 2016 in a speech to the country’s top media officials, Xi lamented that despite China’s rising national strength, its international image was to a great degree moulded by “others” rather than “itself”. He added China was often unable to express itself when it was in the right and that even when spoken, its voice was often not heard. Xi said China contended with three main difficulties: a “deficit” between information inflows into the country and outflows, a “contrast” between China’s true image and subjective impressions of it in the West; and a “drop height” between its hard power and soft power.

After years of trying and billions of yuan in investment, China has little to show for its efforts, let alone addressing Xi’s concerns. Instead, China’s image problem has worsened since Xi replaced China’s long-standing foreign policy of keeping a low profile and biding its time with a more assertive approach widely known as Wolf Warrior diplomacy.

At the session on May 31, Xi called for efforts to develop an international voice that matched its national strength and global status and stressed the need for a narrative tone that reflected openness and confidence, yet conveyed modesty and humility so as to create a “reliable, lovable and respectable” image for the country.